A Deep Dive into Antioxidants & Oxidative Stress

Oxidative Stress: an imbalance between the production of free radicals and the body's ability to neutralize them.

Antioxidants: scavengers of free radicals whose role is to prevent or stop free radical damage, thereby limiting oxidative stress.

Vitamin E: a fat-soluble antioxidant, protects unsaturated lipids and other susceptible membrane components against oxidative damage.

“When I know basic needs are being met, I turn to therapeutic nutrition for health issues. Many times I reach for antioxidants, vitamin E in particular. Because of its versatility and relative safety, I recommend vitamin E for many different types of cases, and always for athletes and neuromuscular issues.”

— Emily Smith, MS, Platinum Performance® Equine Nutritionist

Crossing the literary threshold, "no man is an island" becomes fundamentally pertinent to equine nutrition, as nutrients do not function independently either. It is virtually impossible to single out a specific nutrient when talking about wellness, as the body functions beautifully, holistically as one unit. Nutrients interact in symphony, not separately. Yet, vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) generates tremendous interest and a multitude of questions regarding its usage in horse health. Vitamin E is well known as a powerful antioxidant. Lesser-known benefits include immune support and promoting healthy levels of inflammation. The multiple functions of this versatile vitamin have far-reaching implications.

What is Oxidative Stress?

The paradox of metabolism is such that life on Earth requires oxygen for survival. However, oxygen is a highly reactive molecule that damages living organisms by producing free radicals and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) specifically.

Oxidation is a normal part of everyday metabolism that allows the horse to utilize feedstuffs by turning them into energy. Even though it is critical to life and biologically normal, oxidation produces a noxious side effect — Reactive Oxygen Species. A few well-known ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical and singlet oxygen. These free radicals are unstable atoms that have at least one unpaired electron in their structure and search to stabilize themselves, causing chaos in doing so. They are responsible for damaging the phospholipid layer around cells and cell organelles. They can also destroy enzymes and damage DNA and other cellular proteins. Free radicals can cause considerable irreparable damage to cells and can alter the structure of cell membranes if left uncontrolled. Once formed, these reactive radicals can initiate chain reactions resulting in a havoc-wreaking ripple effect on many other molecules within cells and cell walls resulting in oxidative stress within the animal. Oxidative stress is injurious to cells. It occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of free radicals and the body’s ability to neutralize them via the antioxidant defense systems. Elevated levels of free radicals are produced as a result of exercise, from inhaling air pollutants, ingestion of rancid feeds, a deficiency of endogenous antioxidants and through the exposure to ultraviolet light. Free radicals can also become excessive following injury or disease. Oxidative stress that becomes out of control can overpower the horse’s ability to internally defend itself and may result in tissue damage. This tissue damage has been linked to degenerative disease in several species. Additionally, high oxidation levels may inhibit the immune system.

The Importance of Antioxidants

To aid in the eternal predicament of mopping up metabolic oxidation are the body’s natural defenders: the antioxidants. Essentially, antioxidants are scavengers of free radicals whose role is to prevent or stop free radical damage, thereby limiting oxidative stress. Antioxidants are capable of detoxifying ROS in two ways: by preventing the reactive species from being formed in the first place and by removing them before they can damage the cell. The complex network of antioxidant metabolites and enzymes work synergistically to prevent oxidative damage to cellular components, such as DNA, proteins and lipids.

Antioxidants can be categorized in several ways. One of these ways is by grouping them by solubility: water-soluble or lipid-soluble. The water-soluble group scavenges within the cell and in the blood plasma, while the lipid-soluble antioxidants protect the cell membrane from peroxidation.

Antioxidants can also be grouped as endogenous or exogenous. Endogenous antioxidants are created within the cell itself, and exogenous antioxidants or antioxidant co-factors are consumed in the diet. The body is capable of making five endogenous antioxidants that include superoxide dismutase, alpha-lipoic acid, coenzyme Q10, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. The most familiar exogenous antioxidants are vitamin E and beta-carotene, which is converted into vitamin A internally. Vitamin C is typically considered exogenous in most species, although the horse possesses the enzyme necessary to manufacture this vitamin in the liver. Copper, zinc, manganese, iron and selenium are exogenous co-factors sometimes mislabeled as antioxidants but actually have no antioxidant actions themselves. They are, however, essential for the formation of the endogenous enzymatic antioxidants. For example, selenium is necessary for the formation of glutathione peroxidase. The antioxidant metabolites and enzyme systems appear to have synergistic and interdependent effects on one another where the proper functioning of one relies heavily on the availability of another.

Vitamin E Fast Facts

- Natural form, alpha-tocopherol, is biologically preferential

- Primary fat-soluble antioxidant in the body

- Relies on dietary fat for absorption, particularly when given at high doses

- Works synergistically with selenium

- Serum vitamin E concentrations are considered normal in the range of 1.6-7.5 ug/ml

- Horses on lush grass consume between 1,000-2,000 IU of vitamin E daily

- Upper safe limit for an average-sized 1,100 lb horse is 10,000 IU/day

The Power of Vitamin E

Vitamin E is unique. It is pivotal in the proper functioning for most systems of the horse’s body. The reproductive, muscular, nervous, circulatory and immune systems all rely on vitamin E to some extent. It is in every cell and is distinctive in its supportive role within the spinal cord, brain, liver, eyes, heart, skin and joints. Fats, which are an integral part of all cell membranes, are vulnerable to damage through lipid peroxidation by free radicals. As the major fat-soluble antioxidant, vitamin E utilizes its lipophilic nature by incorporating itself into cell membranes where it protects unsaturated lipids and other susceptible membrane components against oxidative damage. Vitamin E is uniquely suited to intercept peroxyl radicals and thus prevent a chain reaction of lipid oxidation.

Vitamin E is actually made up of two classes of molecules: tocopherols (saturated) and tocotrienols (unsaturated). Although both are available in the diet in several forms, alpha-tocopherol is the form most often found and preferentially absorbed in the body. For other vitamins, a synthetic source is basically identical to the natural source for both efficacy and structure, but this is not the case for vitamin E. The natural source of alpha-tocopherol is clearly preferred biologically in several ways. It is recognized to have significantly higher biological activity, is transported more quickly and stays in the tissues twice as long when compared to the synthetic version. When natural vitamin E is used in feeds and supplements, it is usually labeled as "natural" or "d" (for example, d-alpha-tocopherol or d-alpha-tocopheryl acetate, the esterified and stabilized form).

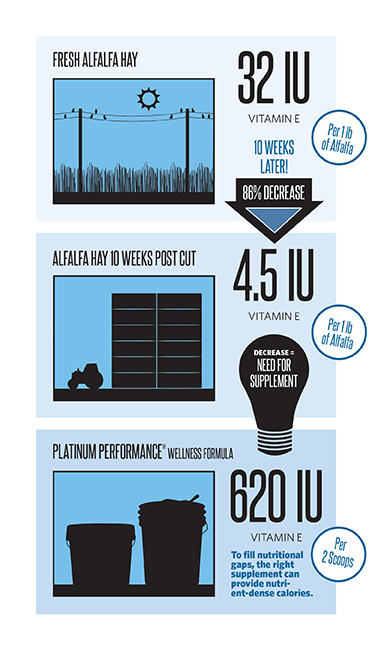

As it is not synthesized within the horse, vitamin E is considered an essential nutrient, and therefore daily consumption is required to maintain adequate blood and tissue levels for cell protection. Fresh, green pasture grass, particularly alfalfa, is an excellent source of natural vitamin E. However, the levels of vitamin E plummet a staggering 86 percent when it is cut, dried and baled for hay. Other factors, such as maturity of pasture and length of storage time once baled dramatically diminish the quantity of vitamin E, with levels being seen to dive tenfold below that of fresh forage.

For all horses that have limited or no access to quality pasture grass, supplemental vitamin E is necessary. This is especially critical management information for newborn foals and growing horses, gestating and lactating mares and performance horses that are being fed stored hay and kept stalled. As the vitamin E requirement is greater for these classes of horses, consuming hay only and being kept in confinement would make them more susceptible to vitamin E deficiency.

Chronic suboptimal vitamin E consumption may result in poor stress tolerance, subpar athletic performance, poor wound healing, muscle weakness and general suppressed immune function. Although most horses with a vitamin E deficiency may not show symptoms, true vitamin E deficiency is linked to several disease states, including several neuromuscular diseases. In young horses, these diseases include nutritional myodegeneration, neuroaxonal dystrophy and equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy. Adult horses may develop vitamin E deficient myopathy or equine motor neuron disease. The symptoms of severe vitamin E deficiency include ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, muscle weakness and fasciculations and damage to the retina of the eye. Measuring blood serum or plasma alpha-tocopherol concentrations is the easiest way to discern if the horse has adequate vitamin E levels. Adequate alpha-tocopherol concentrations are considered to be more than 2 ug/ml, marginal ranges are from 1.5 to 2 ug/ml and a concentration below 1.5 ug/ml is considered deficient.

Noteworthy: Selenium

It would be remiss to have a conversation about vitamin E without also discussing selenium. Both selenium and vitamin E are often referred to as “radical scavengers.” Selenium is a necessary constituent for the enzyme system glutathione peroxidase that functions as a crucial antioxidant compound in the body. The two nutrients work so intimately together that when the intake of one is sufficient, requirements for the other are lowered, and vice versa. When vitamin E is present in the cell membrane, the formation of lipid peroxides decrease. Selenium, as glutathione peroxidase, within the cell fluid will remove the lipid peroxides that do form. If there is inadequate vitamin E, more peroxides are formed, and therefore, more selenium is needed. Conversely, if there is inadequate selenium, fewer peroxides can be removed and, therefore, more vitamin E is needed to prevent peroxide formation. Even though they function synergistically, and even in place of each other, there must be optimal amounts of both to avoid complications from oxidative stress.

Selenium is a topic of anxious concern because it has the potential to be a toxic nutrient. Typically, toxic selenium levels only become a problem if the horse consumes an extremely large amount at one time or if the horse has consumed upwards of 20 mg/day for an extended period. In reality, a selenium deficiency is far more likely to occur due to the fact that many parts of the United States and Canada have inadequate selenium in the soil. Low selenium intake symptoms include poor fertility and myopathy problems.

Recognizing Vitamin E Deficiency & Why It Occurs

Malena Brisbois rather suddenly noticed things were not quite right with her typically very sound and very competitive Swedish warmblood, Amadeus. He was tripping and could not seem to engage his hindend. As a licensed veterinary technician, she knew something was definitely wrong and called her veterinarian, Dr. Anna Russau, for a workup. When the vet came, she had Amadeus work in a tight circle, and the horse just about fell over. Blood work was shipped off and returned showing high titers for equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM). Per Dr. Russau, Amadeus was put on supplemental oil, vitamin E and Marquis, a medication often prescribed for treatment of EPM.

After three months out of work, Amadeus began light training again, as his symptoms had diminished. However, as soon as his body was tested, he started showing problematic signs again. He had trouble turning and continued tripping under saddle. A spinal tap performed at the Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center showed white blood cells in the spine and signaled a parasite attacking the spinal cord. He was taken out of work again in order to conquer this new internal assailant with the aid of a double dose of Panacur, the commonly-used antibiotic Chloramphenicol and continued supplemental vitamin E. When the course of dewormer and antibiotics was finished, Amadeus returned to dressage work with a vengeance. Malena continued the supplemental vitamin E. "After awhile I discontinued it. It was not cheap, and I thought I could get rid of the expense. I thought he would be fine without it," says Malena. A couple of days after removing the supplemental vitamin E from Amadeus’ feeding program, Malena’s trainer asked her if anything had changed in his routine. "My trainer said that he was suddenly having trouble with the second level movements and basically didn’t know where his legs were," recalls Malena. "She wouldn’t ride him. She was scared he was going to fall over in the arena." Malena put her horse back on the vitamin E, and within one week, he was back to normal again. She says, "now I start to panic when I get to running low!"

In 2016, two years after the terrifying parasite episode that could potentially be career ending for many horses, Amadeus was not only back on a full training and showing schedule but was competing at the United States Dressage Finals in Lexington, Kentucky. He and Malena were crowned the champions of the First Level Musical Freestyle — Adult Amateur. Malena says of her comeback kid, "I own and run an equine rehab facility, so I get to see a lot of horses with varying degrees of lameness, health problems and other setbacks. Amadeus’ turnaround is really incredible."

Summing Up Vitamin E

Vitamin E is clearly an integral component in the normal functioning of the horse. There are not many areas that the various properties of vitamin E do not touch in the world of equine nutrition. It is small and simple in nature, yet it produces a complex impact. This is the case when the spotlight is shifted onto any of the quiet warriors that make up the basic fuel of the horse.

Vitamins and minerals, protein, carbohydrates, fat and water are all equally influential in the whole picture of health. Vitamin E is intrinsic in every system, every tissue and every cell, but it is not an island. It is only able to function effectively with adequate selenium, fat to aid absorption and when in sync with the other antioxidants, both exogenous and endogenous. And it remains that there is a multitude of yet unknown contributing factors to the well-being of the horse that make equine nutrition a most fascinating field that has captivated the horse owner and veterinarian alike.

by Emily Smith, MS,

Platinum Performance®