A Journey Through The Multifaceted and Often Misdiagnosed Navicular Syndrome; Exploring Causes, Treatments and Mechanics With Equine Veterinarian Matt Durham, DVM, DACVSMR, and Farrier Lee Olsen, CJF

In life and in medicine, we’re often left with a label. We experience a set of symptoms that seem to match those of many others. Sometimes these symptoms are given a name, and suddenly our ailment has a label. As medicine evolves, researchers and medical practitioners have begun to understand that not every collection of symptoms points toward the same disease, and that labels are simply labels — not necessarily indicative of what’s happening uniquely within each patient. The same can be said for horses, with numerous conditions becoming better understood over time, dissected and tackled with improved diagnostic tools and a more personalized, whole-body approach.

Lower Limb Anatomy

Select Anatomical Structures Relevant to Navicular Syndrome

Navicular syndrome is certainly a disease state that serves as a catch-all label for a singular diagnosis that in fact encompasses many structures surrounding the navicular bone.

©2024 PLATINUM PERFORMANCE, INC./TOPLINE DESIGN

More Than Meets the Eye

Navicular syndrome is certainly one of those disease states, a catch-all label for a singular diagnosis that in fact encompasses many structures surrounding the navicular bone. The syndrome, sometimes called navicular disease or caudal heel pain, describes pain arising from the navicular bone and surrounding structures in the center of a horse’s foot and is a common diagnosis given in cases of forelimb lameness. Veterinarians increasingly don’t refer to it as a disease because disease implies one problem, while syndrome means there are multiple or varying problems.

Horse owners confronted with this diagnosis feel a sinking in the pit of their stomachs. “When I was in vet school (at the University of California at Davis) in the 1990s, navicular syndrome was really simple,” offers Dr. Matt Durham of Platinum Performance®, a longtime equine veterinarian board-certified in sports medicine and rehabilitation. “Navicular disease was just degeneration of the bone. If the horse blocked to the heels and didn’t have a fracture or a nail in the foot, it was navicular disease,” he says of the oversimplified previous thinking. Lee Olsen, a Certified Journeyman Farrier, the highest level of certification from the American Farrier’s Association, and proprietor/operator of Olsen Equine in Weatherford, Texas, agrees: “I always joke when people say that a horse has navicular. I think to myself, ‘The ’90s called; they want their diagnosis back.’”

It wasn’t until advancements in equine veterinary medicine came about — diagnostic imaging in particular — that caregivers realized there was more to the story when a horse is presenting lame and navicular syndrome is a potential explanation. “We know that the navicular bone can degenerate, and those changes can show up radiographically,” explains Dr. Durham. “That’s part of the syndrome, no question. Pain in that area can be very difficult to sort out. Is it related to the deep digital flexor tendon? Is it related to the bone? Is it related to the navicular bursa? A physical exam alone — even with hoof testers and nerve blocks — doesn’t always reveal the full picture. That’s where pursuing further diagnostics really helps, and that includes radiographs, ultrasound, bone scan (nuclear scintigraphy), CT (computed tomography), MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and now PET (positron emission tomography).” These advanced tools provide a more comprehensive, sometimes three-dimensional, view — peeling back the layers of an onion to reveal what’s truly contributing to the lameness. “As a profession, we started to realize that a lot of horses that were being treated for navicular disease might instead have coffin joint disease or involvement of the collateral ligaments of the coffin joint, for instance. In those cases, the navicular bone is there, but it’s not part of the problem,” Dr. Durham points out.

The navicular bone, which helps the large deep digital flexor tendon run smoothly down the back of the foot onto the coffin, or pedal bone, is subjected to significant force from the horse as an athlete. Yet, so are its surrounding and supporting structures: the impar ligament that attaches the navicular bone to the coffin bone; deep digital flexor tendon; first phalanx (known also as P1 or the long pastern); second phalanx (known also as P2 or the short pastern); third phalanx (known also as the coffin bone); and the collateral sesamoidean ligaments that go upward to P1 and create a sling of sorts for the navicular bone.

“All of those structures can be affected along with the navicular bursa, which is the sac containing the fluid that allows for the deep digital flexor tendon to glide past the navicular bone,” Dr. Durham says. “We know all those things can be involved independently or in combination. We’ve also recognized that navicular syndrome itself has a lot more faces than we once thought.”

A term sometimes used to describe navicular syndrome is podotrochlear syndrome. This complicated-sounding term (literally “pulley of the foot”) helps in understanding the function of the navicular bone. Dr. Durham confirms, “If you look at the weight-bearing surface of the coffin joint, about 50% is the navicular bone and 50% is the coffin bone, in terms of the downward force of P2 onto those two bones.” The navicular bone operates in concert with the coffin joint and allows the deep digital flexor tendon to maintain a consistent angle in its attachment to the coffin bone. “If you think about the coffin joint relative to the pastern joint, they’re right next to each other — maybe 2 inches apart,” points out Dr. Durham. “While they may be close, they’re very different in a lot of ways. The pastern joint has a very small amount of flexion and almost no side-to-side movement, also known as collateromotion. In contrast, when a horse is turning in a circle or on a side hill, especially on a hard surface, the foot lands flat, but the limb comes up at an angle. The majority of that motion is occurring at the coffin joint. The navicular bone plays into that a bit too, because it’s able to glide separately relative to P3 and allow for some of that rotational movement that’s normal for a horse. It’s because of this role, however, that the navicular bone experiences a lot of force.”

“A physical exam alone — even with hoof testers and nerve blocks — doesn’t always reveal the full picture. That’s where pursuing further diagnostics really helps, and that includes radiographs, ultrasound, bone scan (nuclear scintigraphy), CT (computed tomography), MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and now PET (positron emission tomography).”

— Dr. Matt Durham

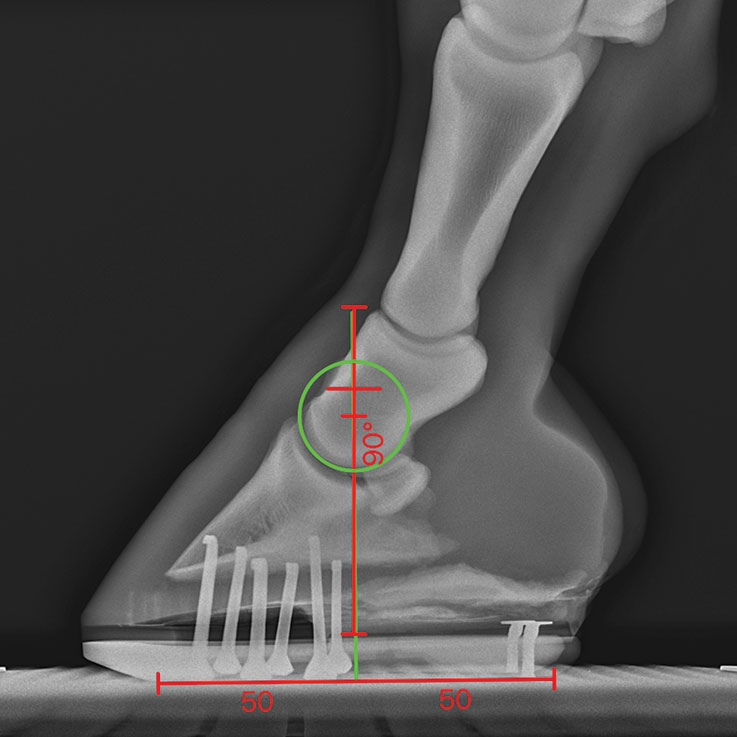

Podiatry radiograph showing a foot balanced with equal parts ahead and behind the center of rotation.

COURTESY OF LEE OLSEN

Podiatry radiograph showing a foot balanced with equal parts ahead and behind the center of rotation.

COURTESY OF LEE OLSEN

Achieving an Accurate Diagnosis

Diagnostic imaging has been a game changer, providing better information to create a more definitive diagnosis for the veterinarian and farrier to use in each individual case. “It’s very rare, in my opinion, that the actual navicular bone is what’s causing the issue,” says Olsen, the hoof-care specialist who helps equine athletes, competing in numerous disciplines, achieve and maintain peak performance through therapeutic shoeing. “I tend to say it’s like the smoke — but where’s the real fire?” he asks rhetorically. This subject is one that is close to his heart, as the chief aim in his daily shoeing practice is alleviating heel pain. “These are horses where people have tried to get them sound with different types of shoeing, and while farriery plays an extremely important role, the right farriery is the key,” he says emphatically.

In terms of true navicular syndrome, horses that genuinely suffer from the condition tend to have a bilateral component to their lameness, while injuries, such as a tear to the deep digital flexor tendon or a collateral ligament injury in the coffin joint, occur more commonly on one side alone. “We’re looking for a choppy gait,” says Dr. Durham of a telltale that something’s amiss in the navicular region. “When a normal horse is in the weight-bearing phase of their gait, they’ll get to the back of the stride, and their foot is way back underneath them. They’re comfortable at that point in the stride. They’re able to fully load the navicular bone, navicular bursa, deep digital flexor tendon and the heel. When they’re all the way back there, that’s when they’re really reaching forward with that opposite foot. What we’ll see in horses with navicular-region pain is a shortened stride and an asymmetrical gait. But sometimes, in horses equally affected in both feet, the horse may not necessarily look lame. There may be no head bob or asymmetry, but if they’re sore in both fronts, they’ll have this sort of sewing machine gait where they’re not really striding out comfortably.”

A typical next step in the evaluation is to begin blocking, injecting a short-acting local anesthetic into a joint or around nerves, to allow a veterinarian to zero in on the source of the issue. “If we block one of the heels — say it’s the right front — and the horse suddenly looks really lame on the left front, that asymmetry shows that the horse was affected in both limbs. In general, we’ll do a lower palmar digital nerve block (numbing among other things the navicular bone, coffin joint, bursa, caudal heel region and sole) since those nerves innervate the sole and the navicular bone,” Dr. Durham explains. “Sometimes a horse that blocks to the heels can have a pastern joint problem or even a fetlock joint problem. The amount of the coffin joint that’s blocked by the heels is also variable. There are a lot of pieces of the puzzle that will present.” In addition to blocking, the way the horse is jogged is also key, focusing on turning rather than straight lines alone. “Some horses are quite lame when you turn them in a circle, with a lot of those cases having a deep digital flexor tendon problem or a collateral ligament problem,” he adds. “We see horses with true navicular pain also becoming stiff in their turns but perhaps not quite as painful when we ask them to go in a circle.” While some cases can show a significant lameness, it’s more common for the horse to exhibit the choppy gait that Dr. Durham mentioned, indicating a problem in the navicular region.

While watching the horse’s movement is useful, diagnostic imaging can help pinpoint the root cause of a lameness. “We’re still using hoof testers. We’re still doing nerve blocks, and we’re still taking radiographs,” says Dr. Durham, who grew up with horses in Reno, Nevada, and decided at age 12 to become an equine veterinarian. “Those radiographs are so critical that I spend more time prepping the foot for a radiograph than I do actually taking the images. I want to see the coffin and navicular bones clearly, and I want to be sure I can get accurate and reproducible measurements.” The images also give the farrier a more complete picture to work with. They tell a story about where the breakover is, what the angles are, where the heels sit relative to the bone and, in many cases, if other factors — coffin joint arthritis or remodeling changes to the navicular bone — are at play. “We’ve teamed up with a local veterinarian here and offer radiographs in our shop because they’re so critical,” says Olsen, who was raised on a cattle ranch in western South Dakota. “So many people waste months and even years with trial and error. If you’ve got a problem and you’re struggling, take your horse to your veterinarian, get him shod right there and take radiographs both before and after the trim. It eliminates the guess work, and, ultimately, the horse will benefit from more intentional and informed shoeing.”

Dr. Durham says after the imaging and physical exam, the horse may still be sore. “At that point, we’ll turn to ultrasound to get a good look at the pastern region and even the coffin joint, looking for changes that we can easily see there,” he explains. Ultrasound is seen as an excellent tool for a speedy evaluation, often available in the field too. While providing further clarity, the equine foot has proven difficult to image using ultrasound and veterinarians have turned to a more sophisticated alternative. “Figuratively, an MRI is priceless,” Olsen says. “Literally speaking, I realize it’s expensive, but it’s a beautiful thing that can often tell your veterinarian and your farrier exactly what’s going on and allow us to work to the problem directly. It gives us something to aim at. I consider radiographs and an MRI to be the cost of owning and riding a good horse that’s struggling. In the long run, you’ll be saving valuable time and money, and, hopefully, shortening the window where that horse is suffering.”

Once an accurate diagnosis has been established, the veterinarian and farrier team up for the treatment.

Once an accurate diagnosis has been established, the veterinarian and farrier team up for the treatment.

While watching the horse’s movement is useful, diagnostic imaging can help pinpoint the root cause of a lameness.

While watching the horse’s movement is useful, diagnostic imaging can help pinpoint the root cause of a lameness.

Treating the Navicular Region

Once an accurate diagnosis has been established, the veterinarian and farrier team up for the treatment. In terms of a medical approach, Dr. Durham explains, “There are several classes of medications that can be used. Good old corticosteroids still work, and I think they’re appropriate in some circumstances.” While certain anti-inflammatories are considered more aggressive than others, steroids certainly have a time and place, mixed in with a little controversy. “To me, it’s a balancing act,” Dr. Durham points out. “We have an inflamed joint that itself is causing harm; it’s already releasing all these enzymes and pro-inflammatory mediators and causing a negative spiral. I’ve heard the argument from some veterinarians that they won’t inject steroids into the joint because they could cause degeneration. On the other hand, so does arthritis itself.

“To me, the debate is really in establishing a line that we shouldn’t cross as veterinarians where injecting steroids will cause more harm than good. It’s not about using no steroids or as much as you can, it’s about using steroids in a targeted way. I avoid corticosteroid injections in horses with concurrent soft tissue injuries like a collateral ligament injury, and there is strong evidence that they should be avoided in horses with metabolic syndrome.” Like many colleagues — especially those treating high-level sport horses — Dr. Durham has moved away from the calendar approach where he sees a horse simply because they’re “due” for injections. “I want to look at the horse and gauge the need, knowing that I’ll likely achieve better results if I see them more often and inject them less often because I’m staying ahead of things,” he says.

A class of drugs known as bisphosphonates, characterized by their ability to bind strongly to bone mineral and their inhibitory effects on mature osteoclasts that break down old or damaged bone cells, is a common treatment for horses with conditions in the navicular region. “We know bone pain is quite painful for the horse and often very difficult to treat with standard anti-inflammatories,” Dr. Durham explains. “While the horse may not necessarily respond to anti-inflammatories in these cases, certain forms of bone pain will respond well to bisphosphonates. On the other hand, some horses with true navicular syndrome won’t respond to these medications at all.” There is debate within the veterinary community surrounding bisphosphonates and for which cases to prescribe them. “A potential disadvantage of bisphosphonates is that they can inhibit bone remodeling to some degree,” he adds. “In those cases, we want that bone remodeling and for the horse to go through that process properly.” Dr. Durham considers himself to be somewhere in the middle of the bisphosphonate controversy. Another drug in a veterinarian’s quiver falls more within its own classification. Dr. Durham says, “Additionally, we find drugs like pentoxifylline to sometimes be helpful in these cases and also in cases of pedal osteitis where there may be bone pain due to pressure from blood within the bone.”

Either as stand-alone treatments or complementary therapies, a more biological treatment approach has emerged in recent decades. “We’re seeing biologicals used more and more,” says Dr. Durham. “One of the big advantages of taking this approach, particularly in a horse where there’s a soft tissue component — perhaps an issue with the coffin joint or a collateral ligament injury — is that we know that using steroids is not ideal because it can inhibit healing in those cases. This is where some of the biologicals can be quite beneficial because they can quiet down a lot of that inflammatory response while not inhibiting the healing process.” The treatment is tailored to the individual horse. “Sometimes it’s a matter of treating the coffin joint because the navicular bone is part of the coffin joint,” details Dr. Durham. “Sometimes, it’s injecting the navicular bursa itself. The bursa is a lot like a joint. It has the same kind of fluid, and its role is to allow that seamless gliding motion between the deep digital flexor tendon and the navicular bone.” By reducing inflammation, veterinarians can potentially improve range of motion in the horse. “In some cases, there are adhesions between the deep digital flexor tendon and the navicular bone itself or parts of the bursa” that can drastically limit range of motion, he adds. When that happens, equine veterinarians can deploy a few tactics including tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA, to break down fibrin (a sort of glue that the body makes), supporting the bursa by targeting adhesions there.

Surgery is also an option in some cases, where the bursa is scoped (known as a navicular bursoscopy) with the hope of improving the range of motion for a horse that otherwise couldn’t achieve improvement. “The other surgical treatment I want to mention is de-nerving, and it’s one that is done less and less these days. I’m glad for that,” says Dr. Durham in earnest. De-nerving essentially desensitizes the foot. While it eliminates the pain, it doesn’t address the underlying condition. “There’s certainly a point where you’ve exhausted all other avenues, and you have a horse that just needs to live a comfortable life. In those cases, it’s a completely valid procedure, but it should not be one of the first things done,” he cautions.

Lastly, Dr. Durham and many veterinarians like him have turned to shockwave therapy — a non-invasive modality that applies focused high-intensity sound waves to hard or soft tissue to stimulate healing — for its benefits to the structures of the foot.

While a diagnosis of navicular syndrome may at first sound hopeless, medical therapies, surgical intervention and corrective shoeing can make a positive impact.

While a diagnosis of navicular syndrome may at first sound hopeless, medical therapies, surgical intervention and corrective shoeing can make a positive impact.

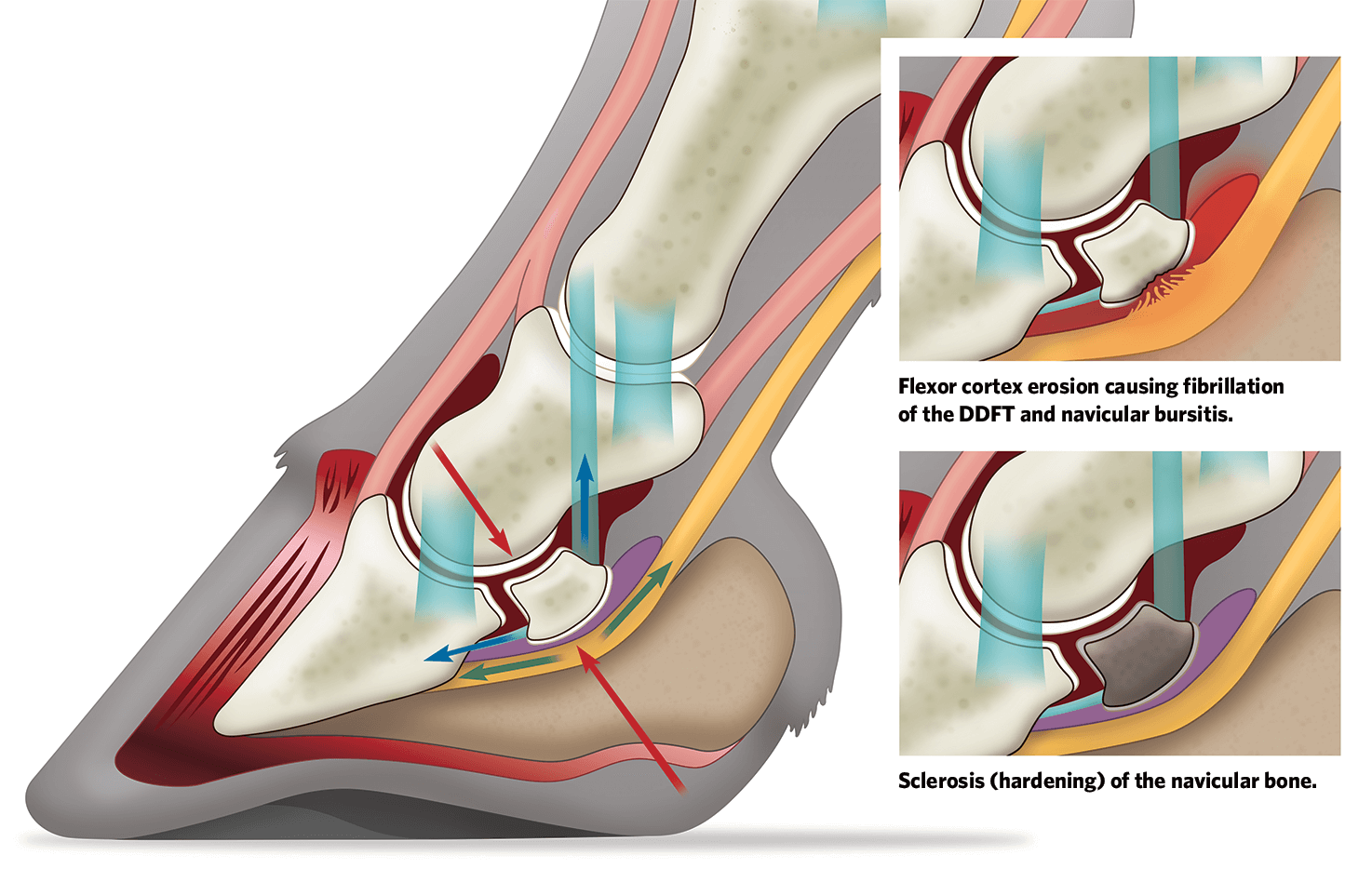

Forces at Work

When Forces Become Unbalanced, Trauma in Various Forms can Lead to Injury

The tension on the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) (green arrows) exerts a force along with the downward force of the limb to compress the navicular bone (red arrows), while at the same time the bone is under tension from the impar and collateral ligaments (blue arrows).

Two variations of navicular syndrome are shown at below.

Two variations of navicular syndrome are shown at right.

Corrective Shoeing

While a diagnosis of navicular syndrome may at first sound hopeless, medical therapies, surgical intervention and corrective shoeing can make a positive impact. The tools at a farrier’s disposal have evolved significantly, though often it’s the masterful application of the basics that make a measurable difference. “When in doubt, get down to a good trim,” says Olsen of his go-to first step with these cases. “You can figure out the mechanics after that.”

A variety of approaches offer farriers options that can be tailored to the individual horse. “A lot of times, especially in a rehab situation, barefoot may be the right choice,” says Olsen of letting the horse go shoeless. “Barefoot allows for a lot more frog pressure. Anytime you put a shoe on a horse, you’re positioning the frog even farther from the ground.” Pressure to the frog can often be the deciding factor in a horse’s comfort level and chance for proper recovery. “So often, the common approach is to get them up and get them back, which theoretically unloads the deep digital flexor tendon. A lot of times, they don’t need all that wedge; they just need some frog support,” continues Olsen, referring to the frequent instance when a horse has a low hoof angle - and the farrier’s natural reaction is to reach for a wedge. Dr. Durham agrees: “If you can change the (hoof) angle through the trim, then they don’t need a wedge, and you can potentially avoid some of those abnormal forces on the heels that can create problems.” Hoof testers and the horse’s behavior will tell a farrier if the horse can handle the newly applied frog pressure. “Barefoot can be a beautiful thing,” emphasizes Olsen. “A very small percentage of the time, the horse can’t go barefoot. A higher percentage of the time, the owner can’t go barefoot.” He’s quick to implore riders to be vigilant when it comes to the surfaces their barefoot horse is walking on, ensuring that the horse isn’t forced to walk on a surface that a barefoot owner wouldn’t want to walk on.

Another shoeing component is known as the breakover, or the point in the horse’s stride when the toe begins to dip and the heel begins to lift. “It’s a buzzword, no doubt,” Olsen says. “Everybody talks about breakover when we’re addressing mechanics. There’s so much more to the picture than just breakover.” He instead shifts his focus to shoeing around the center of rotation. “The coffin joint is a hinge joint; it’s going to hinge back and forth. If you have more out in front and less in back, it’s like trying to be athletic with a clown shoe on. However, if you have the proper 50% in front of the coffin joint and 50% in back, then you have less stress on the coffin joint and the rest of the navicular region.” Ultimately, whether a farrier is shoeing a healthy horse or one with issues within the navicular region, it’s important to treat the horse from a whole-body perspective. “I caution farriers to never be hoof shoeing rather than horse shoeing,” says Olsen in all seriousness. “There’s a whole horse standing in front of you, and it’s all interconnected.

People may see all the specialty shoeing we do on social media, and they assume that we do that on every case. It’s exactly the opposite. An accurate diagnosis, then proper shoeing around the center of rotation will get us further than anything in terms of addressing heel pain. If we jump straight to a wedge, then we’re going to put more pressure on the heel. Think of the heel like a Styrofoam cup, the more pressure you put on it, the more it’s going to come down. The wedge brings the heel even farther from the frog. That’s why incorporating frog pressure is the only way to fix a bad heel. You’ll never fix a sore heel by putting more pressure on it. We have to pay attention to the entire shoe placement and to loading the foot correctly.”

While Olsen is a master of his craft, he insists his approach isn’t necessarily complicated: “What we do isn’t technically hard. If some part of the hoof is hurting, you transfer the load to something else to give it a break. The art and the skill are in knowing where to transfer that load and how much it can take.”

“It’s critical to remember that the hoof is growing every moment of every day, and it takes eight months to a full year to grow out completely. We’re dealing with the horse as an elite athlete, so I want to get the supportive nutrition right every day to maximize potential.”

— Matt Durham, DVM, DACVS, Platinum Performance, Inc.

Advanced Nutritional Support

While shoeing and medicines can impact the outcome, targeted nutrients offer to support the horse from a whole-body perspective and a targeted hoof-centric way. “It’s critical to remember that the hoof is growing every moment of every day, and it takes eight months to a full year to grow out completely,” Dr. Durham highlights. “We’re dealing with the horse as an elite athlete, so I want to get the supportive nutrition right every day to maximize potential.”

Traveling back to pre-1996 when Dr. Doug Herthel was developing Platinum Performance® at Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center in Los Olivos, California, he honed in on omega-3 fatty acids and their unique ability to support every cell in a horse’s body. He recognized that the trillions of cells working synergistically within the horse were turning over rapidly, especially at the coronary band and in the sole. “I was there as an intern at Alamo Pintado (from 1996-97) and learned from Dr. Herthel how critical it is that we nourish these horses properly to support those cells,” Dr. Durham says. While omega-3 fatty acids are vital, so are trace minerals, vitamins and key amino acids, considering that the majority of the hoof is protein.

As veterinary medicine evolves, so has its approach to prevention and treatment. Many horses are elite athletes and performers, and now, more than ever, are conditioned and fed to support not just their overall health but their longevity. “Nearly every athletic horse needs some type of joint and soft tissue support from a nutritional perspective,” says Dr. Durham. His approach, shared by top-level riders, trainers, grooms, farriers and other veterinarians, is to also treat the horse as a walking collection of trillions of connected cells working in harmony for optimal performance. “When you have a foot problem, you have a horse problem,” agrees Olsen. “The world is set up for the quick fix, but, because it takes a hoof so long to grow out, you can’t cut corners and you must have a preventive mindset.”

Proactive care includes annual radiographs performed by a veterinarian.

Proactive care includes annual radiographs performed by a veterinarian.

Proactivity Saves the Day

The pair are strong proponents of preventative care. “I always say, ‘God had a good plan when he built the horse,’” Olsen says. “When we get away from that plan, bad things can happen, and navicular is an example.” Proactivity includes annual radiographs performed by a veterinarian. Olsen adds, “There are so many people who say, ‘My horse has never been lame until now.’ It’s likely not a freak event, but rather, something that acted as the straw that broke the camel’s back; a repetitive strain injury that finally pushed things over the edge.” Dr. Durham adds that problems can fester under the surface in horses that seem fit and fine: “Horses can certainly get by with poor shoeing and poor nutrition, until that moment where they just can’t anymore.”

A rider’s goal is to never set up their horse for failure. Instead, a proactive approach that includes annual radiographs, shoeing to that imagery, while focusing on management and nutrition will help horses succeed and lead longer and more productive lives. The cornerstone is a balanced foot. “A well-balanced foot allows the horse to move better, plain and simple” Dr. Durham offers. A first step toward proactively achieving that balance is seen in the frequency of the horse’s care from veterinarian and farrier. “Especially in sports medicine, we’re doing a better job of that proactive exam where I’m gathering baseline radiographs, then checking in on the horse more frequently,” he adds. “At those visits, I’m asking myself, ‘Is he a little sore to flexion? Is he a little sore to hoof testers?’ I’m trying to find those small things before they turn into that moment where everything unravels.”

According to Olsen, the farrier can contribute significantly to the preventive process. “The No. 1 thing a farrier can do is ask questions,” he says. “It’s one of the best instruments we can use for figuring out what’s going on. If it’s a reined cow horse, how are they when they’re going down the fence? Are they better on one side of the arena versus the other? If it’s a barrel horse, what’s their behavior like on the first barrel, or are they off on the second? With each answer, we’re deducing what’s happening under the surface. Horses are really good at protecting themselves and hiding those discomforts, so I feel a heavy weight to really pay attention.”

Full Circle

Lameness related to the navicular region and more specifically heel pain are extremely common, with true “navicular syndrome” being a somewhat less frequent occurrence than previously thought. From rider to veterinarian and farrier, each member of a horse’s care team plays a role in properly caring for the navicular region and preventing disease and injury from occurring. “I think the role of the veterinarian is to always blame the farrier,” laughs Dr. Durham in jest, referring to the battle of wills that can become a problem between the professions. It’s less of a battle as these key players work together for the betterment of the horse. “Ultimately, we’re both there to serve the horse,” he said. “If we’re in a battle of egos, it’s the horse that loses out the most. My approach is always to try to make the best diagnosis I can, vocalize the principles I’m trying to address, then let the farrier go to work.” Olsen agrees, “Above all, get down to an exact diagnosis. Don’t guess. Work with a good veterinarian and a good farrier to get establishing radiographs and an MRI if the case calls for it. Your farrier can then shoe to those radiographs and request more radiographs to confirm they got it right.”

While there’s no single solution to challenges within the complex navicular region, having a preventive game plan established by trained professionals can go a long way in maintaining overall health, soundness and durability for equine athletes. Farriery and veterinary medicine have evolved separately and together to offer greater knowledge and an array of diagnostics and treatments to benefit the horse. Sometimes, however, it’s still the fundamentals, those profoundly important basics like a good hoof trim and clear and honest communication between humans and horses. “We can get pretty far with a lot of horses if we kind of get out of their way and listen to what they’re trying to tell us,” Dr. Durham says.

The adage of “no hoof, no horse” remains as true today as it has been throughout time. Luckily, dedicated and skillful farriers and veterinarians are melding science and art to care for the intricate structures within the foot.

Platinum Podcast

Navicular Syndrome: Is There More to Know?

Dr. Matt Durham and Farrier Lee Olson take us on a journey through navicular syndrome, its indicators, current treatments, the importance of mechanics and the structures involved.

Listen Now