The Up-Tick in Metabolic-Related Issues and the Subsequent Threat to Equine Health

Much like their physician colleagues, equine veterinarians are seeing an up-tick in metabolic-related issues. It’s a challenge with numerous contributing factors at its core. The industry has seen several breeds and disciplines skew toward heavier horses as their preferred aesthetic. In addition, overfeeding and choosing the wrong feeds can set horses on a path for unchecked weight gain and the often-resulting metabolic concerns that accompany excess fat. While Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) and insulin resistance (IR), which is also often referred to as insulin dysregulation (ID), are serious threats to equine health. These conditions have the distinct advantage of being not only treatable but largely preventable with proper management, a healthy body condition and the right nutrition choices.

In the vast majority of horses, metabolic disease is often treatable with the right nutrition, exercise and veterinary care.

Equine Metabolic Syndrome Defined

Dr. Joe Pluhar of Brazos Valley Equine Hospital in Navasota, Texas, sees his share of metabolic patients and explains the similarities and distinct differences between EMS and IR. “EMS is actually a sub-category of IR … (This is where) the cells in an affected horse do not respond to insulin the way the cells in a normal horse do.” The cause of these metabolic concerns in the horse can range from genetics and incorrect feeding practices to excess weight. EMS requires a clinical diagnosis, but several of the outward tell-tale signs include a cresty neck, increased body condition score, fatty deposits by the tail-head — among other areas — and laminitis. Dr. Pluhar makes an important distinction, “Every EMS horse has IR, but not every insulin resistant horse has EMS. When a horse has EMS, it simply means that their IR has reached a tipping point and the body is having trouble compensating for the inadequate glucose metabolism.”

The Weight Factor

“Adipose (fat or lipid) tissue is metabolically active and able to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory mediators that can damage both the adipose tissue itself as well as other physiologic systems,” says Emily Smith, MS, Equine Clinical Nutritionist with Platinum Performance®. Obesity as it pertains to insulin resistance is a bit of a vicious cycle as elevated insulin triggers the body to store fat, and excess fat reduces insulin sensitivity and increases the physiological need to release yet more insulin. Theories on obesity’s role in poor insulin sensitivity include decreased insulin receptor density following fat-induced cell expansion, alterations in cytokine and hormone levels that affect the cell’s post-receptor response to insulin, and muscle mitochondrial dysfunction with excessive reactive oxygen species release. The gut microbiota is also being considered as a modulating factor. Although obesity is correlated with insulin resistance, not all horses with metabolic concerns are overweight. “Fortunately, in most cases, obesity can be addressed through diet and exercise, although it usually requires a full lifestyle change,” says Smith. Overfeeding, feeding a diet heavy in carbohydrates and sugars, as well as a sedentary lifestyle and lack of exercise are all linked to obesity. Exercise supports insulin sensitivity and helps maintain healthy blood glucose and insulin levels. “Any exercise, even small amounts, can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce production of cytokines that support inflammation. This is important to know even if the horse doesn’t seem to actually lose weight right away. If the horse is not in pain from laminitis or another health issue, moving a sedentary horse even a small amount each day can be beneficial for insulin resistant horses,” Smith points out. Regular exercise and reducing weight through diet and physical activity can support effective insulin activity and go a long way in helping horses return to a more normal metabolic state.

Regardless of whether a heavy horse is experiencing metabolic problems or not, excess weight is a significant contributor to a number of other issues in the horse, including a taxed musculoskeletal system with resulting pain, inflammation and a greater propensity for orthopedic injury. “The extra weight often comes in the form of adipose tissue, which, especially in some regions of the body, has been shown to produce inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins and interleukins, which can also lead to systemic inflammation,” explains Dr. Charlie Scoggin, Staff Theriogenologist and Fertility Clinician at the LeBlanc Reproduction Center at Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. Fat and its impact on the overall health of the horse cannot be underestimated. The heavy horses preferred in some show rings are, in all actuality, horses at risk of serious health conditions.

The Role of Genetics

Gene research may help in the early intervention for and continuous management of certain breeds at a greater risk for obesity. Advances in gene sequencing allow researchers to search for potential markers that highlight an increased risk for easy weight gain or even EMS and IR. If identified, a simple blood test could provide this early warning potential. “Genetics plays a big role in a horse’s metabolic rate and how easily they gain weight,” says Emily Smith. A point readily agreed upon by Dr. Michelle Coleman, Assistant Professor of Large Animal Internal Medicine at Texas A&M University’s College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences. “We believe that EMS occurs as a result of interactions between the environment (diet and exercise) and genetics. We can identify high genetic-risk animals, such as Morgans, Arabians and ponies that develop EMS in the face of appropriate diet and exercise. On the other hand, some horses have lower genetic risk — Thoroughbreds for example — but can still develop EMS, just as any horse can, through exposure to diets high in calories or non-structured carbohydrates,” explains Dr. Coleman. Ongoing genomic research continues with the goal of identifying genes that may increase the risk of EMS, leading hopefully to strategies involving early intervention and more stringent dietary management for horses that have a greater genetic probability to experience metabolic concerns.

How Does EMS Differ from PPID (Cushings Disease)?

EMS and pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) or equine Cushing’s Disease are commonly and mistakenly used interchangeably. Although their symptoms can often present as very similar, their etiology is different, and they can occur independent of one another. “Equine Cushing’s is more correctly identified as pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction,” says Dr. Pluhar. Outward signs of Cushing’s can include a long, coarse, wavy haircoat, abnormal shedding, loss of muscle mass, a noticeable increase in thirst and urination, ulcers in the mouth, as well as a decrease in immune system function. “Cushing’s affects as much as one third of the senior horse population,” points out Emily Smith. “Older horses are more likely to develop this disease, with the average age of affected horses being closer to 20, while EMS is often seen younger, in horses from 6 to 18 years old. However, PPID is seen in non-senior, mature horses as well,” she explains. “In PPID, a progressive degeneration of the hypothalamus of the brain results in a reduction in hypothalamic function, specifically less secretion of dopamine. Dopamine inhibits the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pars intermedia portion of the pituitary gland. With a lack of inhibitory dopamine, the pars intermedia releases excessive metabolically active proteins, including hormones like ACTH. ACTH — typically measured to diagnose PPID — stimulates the adrenal gland to produce cortisol. Excessive cortisol can cause a lot of issues, including decreasing insulin sensitivity in the tissues.”

“Horses that have Cushing’s can have different body conditions, and so it’s very important to treat them as individuals,” says Smith. “If they have Cushing’s, are overweight and struggle with insulin resistance, they will be fed similar to a horse with EMS. If they have a low body condition score, need weight gain and have insulin resistance, they will require a specific diet.” Diets for those horses in particular are kept low in sugar and starch but require a higher level of calories to help them achieve a healthy body condition score. “Quality hay free choice, true low-starch feeds and healthy fats and oils can be very helpful here,” says Smith. “With PPID horses, they need pharmaceutical intervention, specifically pergolide,” adds Dr. Pluhar. “For a PPID patient, I generally increase their caloric intake to counteract the weight loss. I use a lot of Platinum Healthy Weight in these cases as well. Most horses love the taste, and it is a simple way to get a lot of healthy calories into these patients.”

“Nutrition is medicine, and after dealing with thousands of tendon and ligament injuries, I do know that Metabolic Syndrome is a huge factor in their healing patterns and rate of re-injury. I think we can significantly improve that outcome by proper management of diet and disease.”

— Dr. Richard Markell, Renowned Equine Veterinarian & Sports Medicine Practitioner

The Impact of Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS)

Much like in human medicine, the impact of metabolic disorders on the overall health of the horse can be far-reaching and tremendously debilitating. “One of the most concerning downstream effects of metabolic disorders is the onset of laminitis, which can, as we all know, have a crippling effect on the animal,” points out Dr. Scoggin. “All of those fat pockets have extreme inflammatory properties in the fat cells,” agrees Dr. Erin Byrne, boarded Internist at Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center. “That triggers insulin resistance, then the feet get oxygen and glucose deprived,” she explains. “Additionally, when they’re ill they’ll be much more prone to mobilize their fat stores; these tremendous fat deposits get sent to the liver, and the liver is trying to kick out all of these packets of energy. If it can’t keep up the horse can get a fatty liver and potentially sustain permanent damage.” Excess weight and resulting metabolic concerns can impact the function of numerous systems and organs within a horse’s body, leading to long-term damage and also the development of secondary concerns stemming from poor metabolic health.

Treating horses with metabolic issues is handled based on clinical need and the severity of the case. Changes in the horse’s diet and lifestyle are paramount to long-term success, but some horses presenting with clinical signs of these conditions require more urgent medical intervention, in particular, those with laminitis. “If we have a laminitic metabolic horse that’s way overweight, we’ll first draw blood,” says Dr. Byrne of her team’s approach at Alamo Pintado Equine. “We’ll add Thyro-L®, Platinum Metabolic Support and Platinum Hoof Support. We’ll then soak their hay for a minimum of an hour, drain it and get the sugars out. Their feet will be iced, and we’ll use a range of supportive care depending on what the radiographs look like. Metformin will also be used if we have a hard time getting their insulin down.”

In the vast majority of horses, metabolic disease is often treatable with the right nutrition, exercise and veterinary care. Much like in the human type II diabetes epidemic, a horse’s lifestyle and feeding program contribute greatly to their risk for poor metabolic control and the resulting damage to the horse’s health. Speaking practically, Dr. Byrne says, “Prevention is a lot more efficient and cost-effective than treatment and potential loss of use of the horse when you’re dealing with laminitis as an outcome from unchecked EMS.”

Signs of Metabolic Concerns to Watch for

Is Your Horse:

- Between 5 to 18 years old?

- Consuming more energy than he or she is burning with exercise?

- A breed prone to EMS, such as a pony, Paso Fino, Arabian, Morgan, Saddlebred, Warmblood or others?

- Overweight or obese?

- Exhibiting signs of a fatty or “cresty” neck or showing excess fat deposits along his or her back, tailhead or mammary gland?

Proactively Avoiding EMS: What Can You Do?

- Keep your horse at a healthy body condition score, ensuring they do not store excess fat.

- Feed the proper amount of nutrient dense calories with a diet based on high-quality forage, while keeping excess energy from processed grains and concentrates to a minimum.

- Ensure your horse is receiving adequate exercise.

- See your veterinarian for an annual wellness exam, and more frequently for any specific health concerns.

Metabolic Concerns in Reproduction & Fertility

Equine breeders and theriogenologists who manage aged mares with the goal of carrying healthy foals — as well as stallions that also may be affected by metabolic disease — are directly impacted by the EMS. “I think of the impact as affecting three main areas of equine reproduction,” says Dr. Scoggin, “(1) the ability of a mare and stallion to produce quality gametes to maximize the occurrence of fertilization; (2) the quality of the environment (the uterus) where the developing embryo is growing; and (3) the final trimester where the fetus does the majority of its growing and the mare undergoes various physiologic changes in preparation for parturition.” Overweight mares and those experiencing complications from metabolic disease have been shown to have lower success in producing viable embryos and carrying and delivering healthy foals. “Researchers have demonstrated ovulation failure in these mares,” says Dr. Elaine Carnevale, veterinarian and professor at Colorado State University’s Equine Reproduction Laboratory. “Changes in weight can alter metabolic hormones within the follicle, and these hormones can impact fertility. Notably in studies done at CSU in association with Dr. Dawn Bresnahan, we found that the population of lipids within the equine oocyte is altered as the mare goes from a normal to overweight state — changing in prominence from phospholipids to triglycerides. We also noted altered lipids in embryos and more inflammatory markers in uteri of mares that were overweight. Our findings suggest that EMS and obesity can affect reproduction. However, potentially even more importantly, it may impact the early conceptus, with the possibility of influencing the resulting offspring.”

In addition to the significant impact that metabolic problems can have on breeding mares and the potential effects on their offspring, stallions are also subject to breeding challenges associated with EMS. “The impact is expressed in changes with both behavior (reduced libido) and sperm quality (reduced quality and quantity),” says Dr. Scoggin. “Stallions are also not immune to the effects of added weight. Deposition of adipose (fat) tissue within the scrotum can occur, which can then lead to hyperthermia of the testes and subsequent poor sperm production.”

The implications of poor metabolic control can be vast, but this area highlights a direct link between certain metabolic dysfunctions and something as critical as breeding and the health of future generations. It is becoming more apparent that offspring are directly impacted by the weight and/or metabolic standing of their sire and mare.

Metabolic Concerns & the Sport Horse

In recent years, the extent of poor metabolic control in the equine athlete has been increasingly recognized, with research suggesting EMS and IR can impact a horse’s propensity for tendon and ligament injuries, as well as their ability to properly heal from them. “I’m really glad this is finally a conversation,” says Dr. Richard Markell, renowned equine veterinarian and sports medicine practitioner. “There has been significant literature that shows ties between metabolic dysregulation and chronic tendon and ligament injuries on the human side. As it turns out, horses are no different. Those horses that have Metabolic Syndrome are more likely to sustain tendon and ligament injuries, but perhaps more importantly, they’ll have a more difficult time recovering.” As with so many aspects of human and equine health, it all comes back to inflammation. The excess fat in metabolically imbalanced horses is stored in pockets throughout the body and is responsible for the pro-inflammatory cytokines that can increase systemic inflammation and affect various tissues, including tendons and ligaments. In addition, there are certain disciplines where a higher body condition score is preferred, leaving horses more susceptible to the pitfalls of metabolic disease and the subsequent influence on soundness. “If you don’t address the metabolic issues, you’re going to have a slower recovery, a higher incidence of recurrence of injuries and the overall outcome is markedly not as successful,” says Dr. Markell. He, along with so many practitioners today, is a major supporter of a whole-horse approach to veterinary medicine and sports medicine in particular. “The old days where we just thought about treating the tendon, those days are gone. Now, when we have a tendon injury we have to think ‘how do I treat the feet, how do I have a conversation about the work level, footing and training of that horse, how do I manage diet and nutrition, and the most important thing, how do I treat the whole horse not just the injury?’ That’s the exciting part, it gives us the opportunity to treat horses with a much more successful outcome.”

Diet and nutrition play a significant role in the successful management of every horse, but sport horses require the right nutritional intervention due to their varying levels of work, the physical requirements of their discipline and the nuances of their training and show schedules. “While food can’t always fix everything — if it could they wouldn’t have invented medicine — we’re likely going to be unsuccessful as veterinarians if we attempt to manage these conditions without addressing nutrition,” says Dr. Markell, speaking of metabolic sport horses. “Nutrition is medicine, and after dealing with thousands of tendon and ligament injuries, I do know that metabolic syndrome is a huge factor in their healing patterns and rate of re-injury. I think we can significantly improve that outcome by proper management of diet and disease.”

Understanding Insulin Dysregulation

“Insulin sensitivity describes the ability of insulin to pull glucose out of the blood and into body tissues. Insulin resistance (IR) is when the normal concentration of insulin fails to facilitate a normal biological response, usually in reference to insulin- mediated glucose disposal. In these circumstances, circulating levels of insulin are elevated, but glucose may remain normal. It takes more insulin to clear the same amount of glucose,” explains Emily Smith. “The beta cells of the pancreas secrete insulin into the blood stream in response to a rise in blood sugar or glucose. Glucose rises in response to the digestion of non-structural carbohydrates (sugars and starch) in the small intestine. When the horse consumes a high-starch meal, the enzymes of the small intestine will break down the starch into individual glucose units. Glucose exits the small intestine and enters the blood stream to be metabolized for energy in the cells of all the different tissues of the body. Insulin communicates with cells, via receptors, to orchestrate glucose uptake into the cells. Insulin attaches to the receptors that then stimulates the cell to make and send special glucose transporters to the cell membrane, creating an opening so glucose can enter the cell. In insulin resistance, there is a diminished response from the receptors or, if obesity exists, a lower density of receptors on the cell surface, so glucose continues to circulate without being allowed to enter the cell to be metabolized. The non-metabolized glucose molecules remain in the blood, and the pancreas responds by sending out more insulin in an attempt to lower blood glucose. Because the cells are resistant to insulin, hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia can result.”

Clinical diagnosis of IR generally requires one or more blood tests. Basal, non-fasting serum insulin (i.e., up to 3 hours off pasture or forage) has replaced fasting serum insulin, in part because fasting itself presents a stress on the horse that can disrupt insulin function. There are limitations to basal, non-fasting serum insulin, least of which is correlating responses to different sources, quality or type of pasture and forage. Dynamic tests that follow the serum insulin and glucose response to a standardized amount of sugar do require multiple blood draws but are more sensitive at gauging a horse’s insulin sensitivity. Other lab tests have been used to support a diagnosis of IR, as well

Oftentimes, IR is delineated into two categories: compensated and uncompensated. Compensated insulin resistance is when insulin can be produced at a high enough level that eventually cells respond, allowing glucose to enter the cells and returning blood glucose levels to normal. Insulin levels will appear elevated but glucose will remain normal. Uncompensated insulin resistance is when pancreatic beta cells can no longer secrete enough insulin to counteract the current blood glucose level. Blood glucose will not return to normal. Uncompensated insulin resistance is not as common but is indicative of more serious issues. It can accompany advanced stages of PPID.

Why Diet is Crucial

Diet has a profound impact on horses with metabolic disease and their ability to regain health. In these cases, diet and therapeutic nutrition are used as clinical tools by veterinarians to make a measurable difference in their patients. “Diet is used to modify nutrient and caloric intake to restore homeostasis so that all organ systems are working in harmony to create — and maintain — a healthy horse,” explains Dr. Scoggin. “Because obesity can lead to systemic inflammation, getting a horse to — and keeping them at — a healthy body weight can reduce inflammation.” That reduction in inflammation has the ability to directly influence the various systems and functions within a horse’s body, even the health and integrity of their connective tissue. “The goal of a good insulin resistant dietary program (for horses with metabolic disease) is to reduce dietary sugar and starch, which will lessen circulating blood glucose and decrease insulin output from the pancreas,” says Emily Smith. “In my experience, what helps clients is coming up with a simple, straight-forward plan based off their horse’s bloodwork. Too many variables in the diet can make it very hard to stay compliant long-term, and it becomes hard to know what is effective.”

At least part of the problem when it comes to the diet and its role in horses developing metabolic problems, is the energy-rich foods being consumed. “Horses today are not ‘work’ animals anymore; they are typically not pulling carriages or other heavy loads for a living. Many contemporary horses are sedentary or used for ‘light’ leisurely activity,” says Smith. “However, they are often fed well over what their metabolic rate can burn through and so, over time, this leads to weight gain and obesity. But it’s not right to vilify horse owners who are trying so hard to make sure their horses are provided for and receiving the best care. I think it’s an educational opportunity and a reminder to look at what a horse is meant to thrive on: forage. Most modern horses do not need the cereal grains we currently feed; those are reserved for hard work, as they were classically used for. The digestive tract of the horse needs fiber at a steady, consistent pace. The horse was designed this way. It may seem counterintuitive to a lot of people, but these huge animals can not only survive on green fibrous materials but actually thrive on it for many reasons, with a healthy weight being a main benefit.”

Feeding Horses with Metabolic Disorders:

What to Do and What Not to Do

As frustrating as it can be to have a horse suffering from IR or EMS, the distinct silver lining is the fact that, with diet and the correct therapeutic nutrition, these conditions can be successfully managed. A good rule to live by when feeding these horses is that a simplified and wisely-chosen diet can yield significant results, including a decreased weight and reduction in symptoms. “How I like to feed a metabolic horse that is having trouble regulating blood sugar or has high insulin levels on bloodwork is pretty simple,” says Emily Smith.

1. Start with the Hay

Understanding how much sugar and starch is coming from your hay is important, as is having a good grasp of its mineral content. Some hays are naturally better choices for metabolic horses, and if ever in doubt, a hay or pasture analysis can provide more concrete answers.

- Grass hay is a great place to start.

- Alfalfa can, often surprisingly, have a very low nonstructural carbohydrate (NSC) content and can be used in the diet as well if the horse is not sensitive to it.

- Hays will likely vary in their nutrient profile, so a forage analysis is recommended.

- Oat and Barley hay can be good examples of grain hays to avoid.

- Hay pellets or unmolassed beet pulp are excellent carriers for supplements. Beet pulp contains soluble fiber and has one of the lowest glycemic indices of common feeds, even lower than some grass hays. Beet pulp should be soaked before feeding and rinsed until water runs clear.

- If a hay is higher than the desired NSC level or if it is unknown, soak hay for 30-60 minutes to remove some of the soluble sugars. Colder water will require a longer soak time. Discard the water before feeding.

2. How Much Hay Should You Feed Horses with IR or EMS?

Horses should be fed 1.5 to 2 percent of their body weight daily and no less than 1 percent of their body weight in long-stem forage. Although it may be tempting to drastically reduce hay to help facilitate weight loss, severely cutting back can actually worsen insulin resistance and result in serious health complications. Not having access to hay can also be stressful, and these horses should be managed with as low stress as possible as stress increases cortisol, which can increase insulin resistance. Consistently available hay is good for digestive well-being as well as keeping blood sugar levels even.

3. Is the Horse Overweight?

If the horse is overweight and needs to lose weight, they still must be fed no less than 1.5 percent of their body weight daily. Consider a slow feeder. With a slow feeder, the horse can still have free choice access to forage, it just slows them down and elongates the time it takes to go through the same amount of hay.

4. Supplements That Support Metabolic Health

In addition to helping to support healthy levels of glucose and insulin, providing a balanced, comprehensive supplement like Platinum Performance® Equine can ensure the horse is receiving key micronutrients, including omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. For advanced levels of magnesium citrate and chromium yeast, Platinum Metabolic Support can be fed in conjunction with Platinum Performance® Equine.

5. Pay Attention to Pasture

Horses that have access to pasture should graze with caution as sugar and starch levels can vary widely between seasons, months and even within the same day. The safest grazing time in terms of sugar and starch levels is the early morning hours when the night temperatures are above 40° F. Sugar and starch levels increase as the grass is exposed to sunlight with levels peaking in the late afternoon. The grass uses these carbohydrates as fuel for itself during the dark hours and by morning, the levels are at their lowest. Anything that stresses grass such as drought, overgrazing, very short mowing or cold weather will make the grass hold on to sugar and starch for self-preservation and thereby increasing NSC levels.

6. Avoid Grains, Concentrates and Treats

Cereal grains should not be fed to an insulin resistant horse. Cereal grains, such as oats, corn and barley, are high in starch, which breaks down to glucose and consequently elevates insulin. Many feeds that are advertised as low-starch or controlled starch may actually have a combined sugar and starch level in the teens or higher and may be unsuitable to feed to an insulin resistant horse. Refrain from giving treats, even healthy ones, until the horse is at a normal weight.

The Role of Therapeutic Nutrition

A healthy diet based on high-quality forage with low sugar and starch content is key to re-establishing and maintaining a healthy weight in horses. Beyond that, however, are certain therapeutic nutrients that can play a significant role in both preventing metabolic problems and also supporting horses who are experiencing poor metabolic control. Omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants play a critical part in helping to support normal inflammation levels, helping to combat oxidative stress and feeding the body with healthy fats. Further, nutrients such as chromium — to support healthy glucose tolerance and normal blood sugar levels — and magnesium — crucial for the metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins and fats as well as the function of insulin — can be extremely beneficial for horses that are borderline IR or that have been diagnosed with EMS. In borderline IR horses or those with a genetic predisposition to having metabolic problems, Platinum Performance® Equine can be recommended to support total body health, as well as to provide the antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids necessary to support normal levels of inflammation. For some clinical cases, Platinum Metabolic Support is recommended, however, if medically required, Platinum Chromium Yeast or Platinum Magnesium Citrate can be provided independently. PPID cases that may require weight gain can benefit from Platinum Healthy Weight as a pure source of omega-3 rich flax oil infused with vitamin E. Platinum Hoof Support can also be an excellent tool to support healthy hooves.

The combination of a healthy diet with therapeutic nutrients can produce tremendous results in horses with metabolic problems. “In some instances, the results have been profound,” says Dr. Scoggin. “I’ve seen middle-aged broodmares turn into ‘spring chickens’ when you get their weight and metabolic issues under control. They cycle better, breed better and carry their pregnancy better. They are thus more likely to produce a better foal, raise that foal and turn around and get in foal. Thus, metabolic management can have a ripple effect that can resonate through numerous breeding seasons and generations. All these considerations are particularly important in Thoroughbreds because we ask the mares to carry all of their own pregnancies and the stallions must breed each of these mares. In many instances, we are asking these horses to reproduce past their reproductive prime and into their twenties. Managing their metabolic issues early and often keeps these horses healthy and allows them to maintain a lengthy breeding career,” explains Dr. Scoggin.

Which Product?

Metabolic Health

Platinum Performance® Equine

Supports healthy levels of glucose and insulin in addition to digestive efficiency. Studies have shown horses owners can decrease the amount of hay and grain fed.

Buy Now

Metabolic Syndrome

Platinum Metabolic Support

Magnesium citrate and chromium yeast for blood glucose maintenance and insulin effectiveness.

Buy NowAn Industry Shift

Metabolic disorders are undeniably on the rise amongst younger and still actively-showing horses. Where a better understanding of EMS and IR may play a role in reversing this increase, the greatest contributing factor is the industry itself and at what weight certain breeds and disciplines are desired and, perhaps most importantly, what judges deem attractive. “It may be time for a frank discussion,” says Emily Smith. “The body condition that is seen across many show worlds and disciplines, including those of young horses, begs the question, ‘What is too fat?’ The body weight that many horsemen today are considering ideal is, in fact, overweight. Outside of the show arena, many easy keeping, recreational horses also are kept at a body condition score that would often be considered over-conditioned due to lack of exercise or overfeeding, or both. When the overweight horse is considered normal there needs to be an industry shift and a renewed view of horse condition and health. The importance of involving the veterinarian to assess condition is critical as an objective opinion as to whether a horse truly needs to gain weight. It’s an industry standard, so it needs to be an industry shift,” says Smith emphatically.

Addressing metabolic concerns in the sport horse, at least in part, has to begin with the various breed associations and trickle down through judges and their criteria for success in the show ring. “I really applaud associations like the AQHA, for example,” says Dr. Markell. “They recognized that overweight horses with small feet are not healthy. They worked with their judges and changed the selection criteria in the show ring, which changes the definition of a healthy versus an unhealthy horse. That’s important, we’re not doing our animals a favor by overfeeding them, even if the intentions are good.”

“Diet is one of the easiest things we can control when it comes to managing the health of the horse. This is where both veterinarians and horse owners can work together to either manage ongoing metabolic disease or, even better, prevent it.”

— Dr. Charlie Scoggin, Staff Theriogenologist & Fertility Clinician at the LeBlanc Reproduction Center at Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky

Healthy Insulin Response

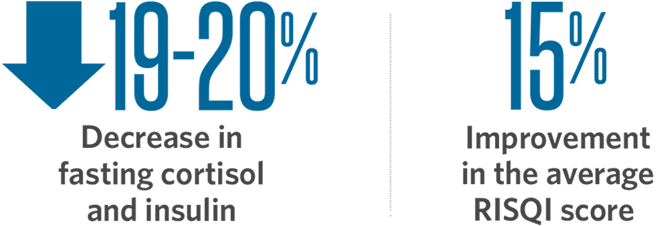

Following 6-8 months of supplementation with Platinum Performance® Equine and Platinum Metabolic Support formulas, borderline insulin- resistant horses had a 19-20% decrease in fasting cortisol (p < 0.05) and insulin (p = 0.052), as reported from a study conducted at Colorado State University. This correlated to a significant 15% improvement in the average RISQI score (an index of insulin resistance).

Changing Tides

With a greater understanding of IR, EMS and PPID and their large-scale impact on overall equine health, great strides are being made in the diagnosis, treatment and, more importantly in the case of EMS and IR, the prevention of these conditions. “I’ve seen horse owners have an increased awareness of the impact that metabolic issues can have on their horses. Whether it’s trying to get them in-foal, improve their stamina or maintain their athleticism, horse owners are becoming more proactive,” notes Dr. Scoggin. “As a veterinarian, I love to work with educated owners because, together, we form a team with the overarching goal of improving and subsequently maintaining the health of the horse.”

Diet and therapeutic nutrition have risen to the forefront and are recognized as mainstays in the management of horses with various metabolic concerns. Results can be profound when diets are made simple, with a focus on low sugar and starch content paired with high-quality forage and appropriate intake of healthy calories depending on the individual horse’s needs. This dietary model, supported by therapeutic nutrition including omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, chromium and magnesium — to name a few — can make a marked clinical impact on metabolic patients. “Diet is one of the easiest things we can control when it comes to managing the health of the horse,” says Dr. Scoggin. “This is where both veterinarians and horse owners can work together to either manage ongoing metabolic disease or, even better, prevent it.”

Research strives in numerous ways to better understand metabolic concerns in the horse, including how to most efficiently diagnose, treat and prevent these disorders. Veterinarians are hopeful that the trend of increasing numbers of metabolic horses with be readily reversed. “There are many potential areas to explore,” says Dr. Coleman. “There is evidence in humans to suggest that the intestinal microbiome (gut bacteria) is intrinsically linked to overall health, including obesity risk. Obesity and obesity-related metabolic disorders are characterized by specific alterations to the composition and function of the gut microbiome in people. There are several studies that suggest the same is true in horses, however, more research needs to be performed to determine the importance of these differences.”

“We have pushed forward tremendously in the past decade with our ability to identify, diagnose, treat and manage these horses. I anticipate continued growth in the coming years,” says Dr. Coleman excitedly. From the potential role of the gut microbiome to improved treatments and cutting-edge nutrition, the scope and impact of metabolic concerns are being better understood and marked as a key area of influence in equine health.

Erin Byrne,

DVM, DACVIM

Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center

Elaine Carnevale,

DVM, MS, PhD

Colorado State University

Charlie Scoggin,

DVM, MS, DACT

Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital

Tara Hembrooke,

MS, PhD

Research Scientist, Platinum

Joe Pluhar,

DVM

Brazos Valley Equine Hospital

Michelle Coleman,

DVM, PhD, DACVIM

Texas A&M; University

Richard Markell,

DVM, MRCVS

Renowned Sport Horse Practitioner

Emily Smith,

MS

Equine Clinical Nutritionist, Platinum

Supporting Literature

1. Di Meo S., Iossa S., Venditti P., Improvement of obesity-linked skeletal muscle insulin resistance by strength and endurance training, J Endocrinol. (2017) 234:R159-R181.

2. Saad M.J., Santos A., Prada P.O., Linking Gut Microbiota and Inflammation to Obesity and Insulin Resistance, Physiology. (2016) 31:283-293.

3. Batatinha H.A.P., Rosa Neto J.C., Kruger K., Inflammatory features of obesity and smoke exposure and the immunologic effects of exercise, Exerc Immunol Rev. (2019) 25:96-111.

4. Sessions-Bresnahan D.R., Carnevale E.M., The effect of equine metabolic syndrome on the ovarian follicular environment, J Anim Sci. (2014) 92:1485-1494.

5. Collins K.H., Herzog W., MacDonald G.Z., Reimer R.A., Rios J.L., Smith I.C., Zernicke R.F., Hart D.A., Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Musculoskeletal Disease: Common Inflammatory Pathways Suggest a Central Role for Loss of Muscle Integrity, Front Physiol. (2018) 9.

6. Durham A.E., Frank N., McGowan C.M., Menzies-Gow N.J., Roelfsema E., Vervuert I., Feige K., Fey K., ECEIM consensus statement on equine metabolic syndrome, J Vet Intern Med. (2019) 6:15423.

7. Otabachian S, Hembrooke T, Carnevale E, et al. Effects of Fatty Acid Supplementation on Insulin Sensitivity in Old Mares: A Preliminary Study. Abstract Only. J Eq Vet Sci 2011;31.

by Jessie Bengoa,

Platinum Performance®