How Skilled Equine Veterinarians and Farriers are Propelling The Prevention and Treatment of Laminitis Forward For The Horse

Perhaps one of the most devastating of all equine disease states, laminitis has claimed the lives of countless horses due to innumerable causes. Its impact is unquestionably destructive (if not deadly), its causes are a moving target, and its treatment is an ever-evolving landscape based on novel research and techniques from the field. The disease itself doesn’t discriminate — laminitis has claimed every age, breed and discipline, from beloved backyard ponies to revered track superstars, including legends Secretariat and Barbaro. Laminitis is known for its pain and difficulty to treat once clinical, and veterinarians continue to press forward, seeking more effective therapies, advanced shoeing techniques and, arguably most importantly, research-backed preventive measures to help recognize horses with a propensity for the condition and intervene before it’s too late.

“Few diseases are more frustrating to veterinarians and farriers than treating equine laminitis.”

— Stephen O’Grady, DVM, MRCVS

Virginia Therapeutic Farriery

Understanding Laminitis

To fully understand laminitis, as much as equine veterinary medicine is able to do so currently, you first have to grasp the nuances of the equine foot. “We have to understand the hoof capsule and P3 within,” says Dr. Mark Silverman, a highly-respected sport horse veterinarian, skilled farrier and former dressage trainer, of Sporthorse Veterinary Services in Southern California, referencing the bone at the base of the foot known by various labels such as the coffin bone, pedal bone, distal phalanx, third phalanx or P3. The coffin bone is attached to the inner hoof wall by the lamellae, which is a soft tissue structure that contains both nerves and blood supply. “Think of the lamellae or laminar structure as living VELCRO®,” he continues. “The laminar structure wraps around the bone and VELCROs the P3 into the hoof capsule.” In the case of laminitis, we’re seeing significant inflammation and damage that has occurred to the lamellae, which in turn can directly impact the coffin bone or P3. Dr. Stephen O’Grady agrees, maintaining that the air of mystery surrounding laminitis boils down to that interior hoof structure. A world-renowned veterinarian and expert farrier whose life’s work has centered on understanding and treating laminitis, Dr. O’Grady has developed a keen sense of the disease after decades treating laminitic patients both medically and through therapeutic farriery. “The lamellae is a soft tissue structure enclosed within a rigid structure — the hoof capsule,” explains Dr. O’Grady. He points out that soft tissue structures within the hoof capsule present numerous challenges when laminitis comes into play. “You have edema (swelling) occurring in a rigid confined space, resulting in pain and decreased blood supply,” says Dr. O’Grady. In plain terms, as the tissue swells, it has nowhere to go, causing the affected animal extreme pain. “It’s almost like treating a disease in a box. You can’t see it, you can’t feel it, you can’t palpate it and you can’t look at it. It’s like no other,” he says of the blind atmosphere veterinarians are forced to work with in these cases. To say the least, experience, skill and a good dose of luck come into play.

Though laminitis appears suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere in many cases, the disease has likely been brewing in a subclinical state for a period of time before it is triggered and shows clinical signs. “One of the biggest challenges, other than the obvious pain the horse is going through, is that the client has a horse that was perfectly normal yesterday, they came to the barn today and the horse has crashed; the horse has gone through a catastrophic change,” says Dr. Silverman. “An important factor to remember is that most of the damage done to the feet happened before the horse was painful, before they were showing symptoms. When they’re painful, you’re past the developmental phase and the horse has likely already suffered basement membrane damage and mechanical changes in the feet that are very often not going to return to normal despite our best efforts,” explains Dr. Silverman.

Even beyond the fascinating inner workings of the equine foot and the mechanics that play out during a laminitic episode, the million-dollar question is not simply what is happening, but why? Recently, from the Equine Sciences Department at the University at Liverpool, Cathy McGowan, BVSc, MACVSc, DEIM, DECEIM, PhD, FHEA, FRCVS, identified three distinct pathways to the development of laminitis. These three primary classifications of laminitis are (1) sepsis-related laminitis, 2) endocrinopathic (or metabolically related) laminitis and 3) support-limb (or contralateral-limb) laminitis. While each avenue represents its own path into the disease state, all have several commonalities in the pathophysiology that occurs, the underlying damage to the lamellae and structure of the hoof, the treatment protocols put into action in an acute phase and the ongoing management practices used to treat chronic cases of laminitis.

Ultimately, regardless of the type of laminitis case in front of a veterinarian, and beyond the pain and edema, there is damage to the hoof itself occurring due to numerous factors including inflammation, ischemia and the resulting tissue damage and displacement. The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) explains that “inflammation often permanently weakens the lamellae and interferes with the wall/bone bond. In severe cases, the bone and the hoof wall can separate. In these situations, the coffin bone (P3) may rotate within the foot, be displaced downward or may ‘sink’ and eventually penetrate the sole.” Dr. Andrew Parks explains further, saying “There’s some displacement that occurs, typically in three patterns. You get rotation, you get sinking and now we know that you can get asymmetrical sinking.” Dr. Parks, of the University of Georgia, has a long-standing interest in the relationship between the form and function of the horse’s foot and the diseases that affect it. As he pointed out, displacement is a significant concern in laminitis cases, complicated by the load of the 1,000-pound horse bearing down on the structure of the foot and the fact that the lamellae experiences not only significant damage following a laminitis episode but is complicated by disruption of the normal vascular architecture of the foot following displacement.

With the initial inflammation and ischemia colliding head-on, this begs the question, where is the high level of pain primarily coming from in laminitis cases? “The answer is that we really don’t definitively know,” says Dr. O’Grady in earnest. “We know where pain receptors are in the rest of the tissue — in the skin, the subchondral bone, the joint capsules and so on. We assume that it’s the same pain receptors in the lamellae. If the lamellae are damaged, are these pain receptors working?” he asks of a question still unanswered in veterinary medicine. “Ischemia does have to be considered,” says Dr. O’Grady. “If tissue starts to die (necrosis), that’s painful.” Dr. Silverman echoes the question of ischemia versus inflammation and essentially, which bears responsibility as the primary culprit of the pain and degeneration occurring within the foot? “Is it an ischemic event or a catastrophic amount of inflammation which has increased blood flow to the feet?” he asked rhetorically. “Which is it? At one point we’re talking about it being a lack of blood flow to the feet, but wait a minute, if it's inflammation you may have increased blood flow to the area, which produces that throbbing pulse and increased heat. In that case, the ischemic event — that lack of blood flow — may be a secondary effect. It’s a quandary.”

It’s the ever-present questions that linger in the minds of equine veterinarians coupled with the wildly-different response to treatment seen in one laminitis case to the next that has veterinarians continually challenged by the disease. “Few diseases are more frustrating to veterinarians and farriers than treating equine laminitis,” says Dr. O’Grady.

Three Main Types of Displacement of the Distal Phalanx

The below schematics depict the three main types of displacement of the distal phalanx that occur in horses with laminitis. On the left are three images (labeled A) that depict the anatomical changes in the sagittal plane (along the axis of the limb) and on the right are three images (labeled B) that depict the anatomical changes in the frontal plane (cross section from outside to inside of the limb).

Figures 1A and 1B demonstrate anatomical changes that occur with rotation: the distal phalanx rotates in the sagittal plane, so the dorsal surface of the wall and distal phalanx are no longer parallel and push down on the sole (1A) but not much is evident in the frontal plane (1B).

Figures 2A and 2B demonstrate the anatomical changes associated with sinking or distal displacement: the lamellae all around the foot are damaged and the distal phalanx drops down and the sole is depressed, but the alignment of the phalanges stays the same and the dorsal surface of the distal phalanx and hoof wall remain parallel.

Figures 3A and 3B demonstrate the anatomical changes associated with unilateral sinking or distal displacement: one side of the distal phalanx pulls away from the hoof wall and depresses the sole on one side and the distal interphalangeal joint (coffin joint) opens up on the affected side (3B) but not much change may be evident in the sagittal plane (3A).

SOURCE: ANDREW PARKS, MA, VET MB, MRCVS, DACVS

Sepsis-Related Laminitis

Sepsis-related cases represent one of three primary causes of laminitis and bring their own challenges to the table. Here, laminitis is occurring as a secondary condition following another serious medical event, such as in post-colic or post-pleuropneumonia cases, or as Dr. Craig Lesser adds, “These cases are also seen post dystocia or retained placentas, or post-colitis where they get a toxic shower to their feet,” he says. Dr. Lesser, like Drs. O’Grady and Silverman, is both a trained farrier and veterinarian who sees a high volume of laminitis cases. Along with colleagues Drs. Scott Morrison, Raul Bras and Scott Fleming, Dr. Lesser is a pivotal figure within Rood & Riddle’s Equine Podiatry Center in Lexington, Kentucky. Dr. Silverman echoes Dr. Lesser’s assessment, “It’s very complicated because you’re treating a horse that’s got a catastrophic disease on top of a catastrophic disease. You’re fighting two different fronts at the same time with these toxemias.” While treatment of sepsis-related cases is heavily dependent on individual circumstances, a veterinarian’s primary concern is getting the root cause under control first, which typically translates to removing any remnants of the placenta or getting diarrhea under control as quickly as possible. “We’re providing a lot of mechanical support for these horses,” says Dr. Lesser. “They’re usually on anti-endotoxic doses of NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) to control the sepsis and mitigate inflammation.” In Dr. Lesser’s cases at Rood & Riddle, he and his colleagues operate with a team approach between the Medicine and Podiatry departments. “If a horse has increased pulses and they’re with our medicine department, they’ll usually immediately have us come in to take radiographs. This gives us a good baseline and history for the horse. We’re taking a more proactive approach versus waiting until they’re sore-footed. We’re really getting out there early.”

Endocrinopathic Laminitis

The second and perhaps most prolific of the primary causes behind this devastating disease is also considered the most avoidable at the same time. “Endocrinopathic laminitis is associated with insulin dysregulation and is often part of the group of risk factors defined as equine metabolic syndrome (EMS),” says Meri Stratton-Phelps, DVM, MPVM, DACVIM, (LAIM), DACVN, Equine Clinical Nutritionist with Platinum Performance®. “The laminitis cases I see most often are related to overweight horses and EMS,” agrees Dr. Erin Byrne, a boarded internist widely regarded for her insight and experience with laminitis at the highly-respected Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center in California. “We’re seeing high insulin combined with a glucose-deprived lamellae and restricted blood flow. It’s a bad combination. So often people don’t think of their horse as overweight. They think, ‘I can see the hint of some ribs, he’s good.’ In reality, they’re missing the signs of a cresty neck with the telltale fat pouches. The whole body may not look particularly overweight, but those fat deposits are huge inflammatory producers,” explains Dr. Byrne. While many metabolically-related laminitis cases can be greatly improved or even reversed with proper diet and exercise, including the underwater treadmill as a key rehabilitation tool, a lot depends on the age, general health and hoof quality of the horse, in addition to how quickly the horse begins treatment and dietary intervention to mitigate the damage done by laminitis. “What can make the difference in the outcome we’re able to obtain is how soon these horses get to us. We have to catch it early enough. I tell horse owners, if you have an overweight horse and there’s a lameness that presents, laminitis has to be considered,” says Dr. Byrne. “The faster you get on it, the better. Even if the horse has to be trailered to the clinic, you’re still better for it. Get them in Soft-Ride Boots® and get them somewhere quickly where they can be managed,” she urges.

A frustration seen with this type of laminitis is often that the horse is overweight yet going about its daily life in a subclinical state for a given period of time, unbeknownst to the owner. Horses with insulin dysregulation or undiagnosed (or diagnosed) EMS are at a significant risk for laminitis, plain and simple, and can be triggered into a clinical state by any number of insults. “Let’s face it. I’m in the dressage industry,” says Dr. Silverman. “We tend to go towards full-figured or ‘Rubenesque’ horses if you want to be kind. Many of these horses have been grossly overweight for generations — they’re kept overweight and they’re athletes. They have the early warning signs of the cresty neck and let me tell you, it’s not a sign of a powerful horse — it’s a sign of fat distribution, it’s not muscle,” he says frankly. These cases exemplify the necessity of regular veterinary wellness care, allowing veterinarians to pull blood, test the horse’s metabolic status and create a baseline by which things can be monitored, managed and quickly mitigated should their metabolic health reach a critical point. “You can predict some of these horses are heading down a pathway where you don’t want them to go,” says Dr. Silverman.

While endocrine-related cases of laminitis are frustrating because they are oftentimes avoidable with weight management, they are equally as challenging due to their recurrence. “One of the challenges of the endocrine-based disease is, not only do these horses tend to founder once, they then carry the insult with them as they go forward. They don’t get past that disease, and it’s ever-present for the rest of their lives,” says Dr. Silverman of the reality of having to continually manage these cases.

Support Limb Laminitis (SLL)

Perhaps some of the most heartbreaking and public cases of laminitis are seen in the support-limb category, which is the third of the three main causes of laminitis. Through history the world has watched otherwise healthy and fit horses suffer an orthopedic injury — a broken bone or joint infection to name a few. The horse then enters a hospital setting, undergoes surgery in some cases, appears to be on the road to recovery, then is lost to laminitis. It’s a gut-wrenching experience for veterinarians when losing a patient to laminitis after successfully repairing a fracture or treating another challenging orthopedic injury. Not many would argue that one of the most followed laminitis cases of all time was that of Barbaro, the striking Thoroughbred that claimed a decisive victory in the 2006 Kentucky Derby only to shatter his leg just two weeks later in the Preakness Stakes. Operated on and hospitalized at University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center, Barbaro received exceptional care from leading experts in the field. Referring to Barbaro, Dr. O’Grady shares that “In the early stage after he was operated on, he was observed to be standing on the operated limb/foot, yet he came down with laminitis in the contralateral foot.” His point is clear — Barbaro had every advantage in top-level care, generally decent weight distribution, constant monitoring and all available treatments, yet he still developed laminitis and eventually succumbed to it. Even with otherwise excellent health and youth on his side, he was lost to the unrelenting disease. The question for his case and others like him is why? “Was it stress, the hospital atmosphere, the fluids, the medication, a lack of oxygen? The truth is we don’t know,” says Dr. O’Grady honestly. His point is illustrative of the often-frustrating mystery surrounding the root cause of a laminitis case involving the contralateral foot.

In the case of support-limb laminitis, horses in the at-risk category include those that have experienced an injury, orthopedic surgery or clinical situation of some kind that preferentially shifts their weight from the injured limb to the contralateral limb. “If you have an injury, for instance, to a front leg, a fracture or something that’s repaired, you can understand that this horse goes through a period of healing. This healing may take several months on average for a young, healthy individual that’s had a fracture,” explains Dr. James Orsini, Associate Professor of Surgery at the famed New Bolton Center and former Director of the Center’s own Laminitis Institute. Dr. Orsini is a pillar in the academic community regarding laminitis and has helped move the profession forward in terms of its impact on this disease. “There are pain medications that we can use to encourage some weight-bearing until fracture healing is far enough along to support weight. Normally, horses shift their weight rhythmically and regularly over time as a means to ‘pump’ blood from the foot back to the central circulation. The foot is the pump returning venous blood and metabolic byproducts, including carbon dioxide and lactate, from the lower limb and the foot up to the heart, liver, kidneys and so on for processing and excretion,” Dr. Orsini explains. Just as important as returning blood and byproducts from the foot is the transportation of a fresh supply of oxygen and glucose to the foot. The equine foot requires a large amount of glucose to sustain itself, even larger than that required by the brain. “If a horse has sustained a severe injury in one leg, they end up disproportionately bearing weight on the opposite leg and not necessarily the diagonal leg, but this certainly can happen as well,” says Dr. Orsini. “Over a period of 2 to 3 weeks or longer, this can result in either slow cellular death or degeneration of the tissues that suspend that third phalanx or coffin bone in the support leg,” he says, painting a picture of how laminitis develops as a result of a severe orthopedic event. “Approximately 60 percent of a horse’s body weight is carried by the front limbs and feet versus roughly 40 percent on the hind feet. Therefore, because of this difference in weight-baring, forelimb laminitis is much more common,” he explains.

In orthopedic cases, laminitis is often at play as a risk factor, motivating veterinary teams to treat orthopedic injuries and post-operative cases as aggressively as possible for quick and efficient healing in an effort to avoid the threat of laminitis. “We certainly want to treat them aggressively and as soon as possible to try to return the injured limb to some semblance of normal, or at least to improve the ability for the horse to heal in a normal ‘biological’ system,” says Dr. Orsini.

“We’re very proactive,” agrees Dr. Lesser. “We’ll often put a big wedge on these horses, which will help alleviate the loaded leg mechanically. This wedge reduces the pull of the DDFT (deep digital flexor tendon) on the coffin bone (P3) and in doing so reduces the pull against the lamina before it becomes inflamed or rotation occurs. If laminitis does occur, then we’re trying to figure out what we need to do above our initial mechanics.” All efforts are made to maintain the critical weight shifting that must continually take place. “When you see a horse that’s mildly uncomfortable, and he’s switching feet back and forth, that isn’t the horse that’s in trouble,” points out Dr. Silverman, showcasing that it’s the horses relying primarily on the foot opposite their injured limb that see the greatest risk for support-limb laminitis.

Above, a chronic laminitic foot with a significant laminar wedge that has been trimmed. Coronary band indicates unilateral displacement.

IMAGE COURTESY OF MARK SILVERMAN, DVM

A glue-on shoe that is often used in chronic laminitis cases to provide core support and eased breakover mechanics.

IMAGE COURTESY OF MARK SILVERMAN, DVM

“As veterinarians, we value science and solving problems, of course, but it’s also our ability to improve the health and welfare of the animals we take care of and the lives of the people who love them.”

— James Orsini, DVM, DACVS

Associate Professor of Surgery and Former Director of the Laminitis Institute New Bolton Center, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

Diagnostics and the Physical Exam

Concerning diagnostics and a physical assessment of a laminitis case, there will inevitably be a different course charted for acute versus chronic cases. In acute laminitis cases, the inflammatory cascade has accelerated in the hoof capsule and the race is on to halt further damage, manage pain and inflammation and do so in as timely a manner as possible. Without exaggeration, it can very often be a life or death scenario. Establishing a quick and accurate gauge of where the horse is in the disease process and what level of damage has occurred is imperative to choosing the correct course of treatment. “I start by taking a step back and watching the horse move,” says Dr. Lesser of his simple first step in assessing a case. “We have Obel scoring methods and laminitic grades to help establish the severity of the case, which are very broad but helpful categories to begin with.” Dr. Lesser then moves on to examining the quality of the hoof itself, looking for rings and whether they are divergent from the toe to the heel, assessing the sole and seeing whether the foot is concave or convex. “From there, we’ll start with digital pulses, see if there’s an increased pulse in the affected feet and compare it to the opposite front leg or the hind.” Next, he’ll palpate the coronary bands. “This is overlooked surprisingly often, but I find it to be the most useful tool.” This can help determine if any sinking has occurred, amongst other valuable insights. From there, he prefers to get foot radiographs if the client agrees to move forward. The severity of those radiographs determines the next step forward. With each diagnostic tool, imaging and visual assessment, Dr. Lesser and veterinarians like him are establishing their game plan for treatment based on a clear end goal that must be established early on with the client.

In contrast to the physical exam and diagnostics used in acute cases, Dr. O’Grady is a prime example of a referral veterinarian brought in as a second, third or fourth opinion on chronic laminitis cases. Prior to taking on a case, Dr. O’Grady regards the horse’s history as an imperative piece to the puzzle. Four components run through his head as a mental checklist when assessing his possible involvement in a case. “First, I want to know what happened to this horse. Secondly, I want to have photographs of the hoof,” says Dr. O’Grady. “Third, I want radiographs.” This allows Dr. O’Grady to establish a more complete picture of the patient, the full spectrum of the case and an early idea of what the prognosis may be in relation to the client’s goals for the horse. “Aside from the imaging and medical history, I’m going to ask a lot of pressing questions when someone wants me to look at a case — ‘Do we know what caused it? What treatments have been done? What do the X-rays look like and do I have enough healthy tissue where I can change this horse’s foot around and get the bone realigned in the hoof capsule?’ ” His fourth and final step is being realistic and frank about the horse’s at-home care. “Believe it or not, I want to understand the caretaker. Are they going to carry out the proposed treatment plan?”

After the case history has been established, Dr. O’Grady then moves through a series of steps to assess the status of the horse. He begins by examining the conformation of the feet, noting that “each foot conformation is going to have an influence on the laminitis and our ability to resolve that case.” Next up, he carefully examines the radiographs to glean all of the information he can and use the imaging as a template for the foot. The physical examination follows, with Dr. O’Grady looking for several key specifics including how the horse walks — is he landing toe or heel first, does the horse have a pronounced toe flip or a short, stilted gate and is he reluctant to walk out of the stall? Another key indicator is how the horse moves when turned. “I’m looking to see if he turns on his back feet and lifts his body up to turn around,” which is a clear indication of pain. Dr. Parks, a close friend and colleague of Dr. O’Grady adds to the list they both follow. “I want to see if the heels are high, if the growth rings are narrower at the coronary band from the toe, if the sole surface is depressed and if there are hemorrhages in the sole,” he says. “There’s quite a lot to go on.” After the initial visual assessment, Dr. O’Grady explains the deeper steps he’ll take, including determining if the horse is growing hoof wall at the coronet above the toe and to gauge the presence of a subtle ledge in the toe where the bone may have sunk slightly. “I also look for a club foot,” he says. “Unfortunately, they make the case tough because the muscle tendon unit is already shortened.” Beyond the crucial case specifics that are established from a visual examination, Dr. O’Grady considers the use of hoof testers to be crucial. “The hoof tester examination not only shows me where the horse is painful, but when you use the hoof testers, you’re also using them to see if the sole deforms along with assessing the integrity of the hoof structures. In other words, how thin is it? Is there separation in the sole wall junction of the hoof capsule?” he asks. Considering his long background as a farrier, Dr. O’Grady gravitates toward hoof testers and his experience in using the information they deliver. Dr. Parks agrees that “hoof testers don’t just test for pain in the sole but they test for pain in any tissue in between the jaws (of the testers), which could include the wall,” he explains.

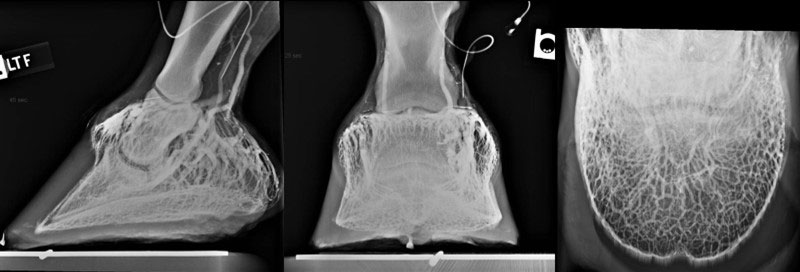

The most definitive diagnostic tool used in both acute and chronic cases is seen in the vital radiographs that are taken to assess the status of the foot and level of damage at hand. “Veterinarians now take two radiographs,” says Dr. O’Grady, referring to a dorsopalmar (DP) view as well as laterals. “The lateral view only looks at the position of the distal phalanx within the hoof capsule in the sagittal plane. Adding a dorsopalmar 0°DP view notes the position of the distal phalanx in the frontal plane. This allows veterinarians to see both downward and side-to-side rotation,” explains Dr. O’Grady. “You cannot tell from a single lateral radiograph whether the animal’s distal phalanx is moving in the frontal plane,” adds Dr. Parks. “Baseline radiographs for horses that have been developing serious diseases are incredibly useful as a way to follow the progress of disease and the success of a treatment,” he says.

Additionally, venograms are a debated imaging tool sometimes used in laminitis patients. While some veterinarians include the use of venograms as a standard of care in many of the laminitis cases they encounter, others don’t find the information gleaned from a venogram to be of enough value to justify the cost or risk associated with blocking the horse to perform this type of imaging. “I do not criticize or condemn the use of venograms,” says Dr. O’Grady, speaking of the imaging tool used to visualize the vascular system within the foot. “With that said, I don’t use them. The reason being that I’ve not had a venogram change the way I would treat a laminitic horse.” Dr. O’Grady adds another valuable point by way of his aversion to the use of venograms in certain acute laminitis cases. “If you see a horse for the first time and it’s an acute case where the horse is planted to the ground, in order to do a venogram the veterinarian will have to anesthetize or block the foot. In an acute case, I do not want to block those feet because that horse is going to be standing or walking around on compromised lamellae for four to five hours. The only time I’ll block a laminitic horse’s foot is if I’m going to do a tenotomy (surgical cutting of a tendon) and operate on him, that’s it. Most procedures on a laminitic horse can be performed with appropriate sedation. Otherwise, that horse can do a lot of damage to that blocked foot in a couple of hours of walking around on compromised lamellae,” he points out. “Finally, despite its existence for decades, there remains an absence of any peer-reviewed published data supporting the diagnostic or prognostic value of a venogram for managing laminitis.”

“(Cryotherapy is) probably the most useful tool outside of NSAIDs for me. I’ve found it to be very effective at diffusing inflammation.”

— Craig Lesser, DVM, CF

Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital

Cryotherapy

While laminitis may be an incredibly complex and nuanced disease state, one of its front-line treatments in the acute stage illustrates that sometimes simple is, in fact, best. “Number one is ice,” says Dr. O’Grady. With much evidence behind it, veterinarians know that placing the affected limb in a continuous ice slurry for the first 36-72 hours of treatment, depending on the case, can be of tremendous benefit to the patient. “You need to have ice, preferably in a slurry, going up the legs from above the fetlock down. Simply standing a horse in cold water with ice cubes doesn’t get the job done.” Dr. Lesser agrees, “It’s probably the most useful tool outside of NSAIDs for me. I’ve found it to be very effective at diffusing inflammation.”

For Dr. Orsini, cryotherapy has been a research passion for several decades. “Cryotherapy used appropriately on the feet can prevent laminitis. It’s simple, effective and can be used anyplace,” he says of the many advantages. While relatively simple by nature, cryotherapy has hard science and proven technology behind it. “Maintaining the foot temperature in the 5-10°C range seems to be the target,” says Dr. Orsini. Icing has several benefits from both a preventive and therapeutic standpoint. “It’s anti-inflammatory, and we know that reducing inflammation is the hallmark in preventing laminitis,” says Dr. Orsini definitively. “It actually puts the foot almost into a state of ‘hibernation.’ Anything that’s chilled and cooled requires less oxygen and glucose. What you’re doing is downregulating the level of oxygen and glucose a foot or organ needs, and that equals prolonging and protecting the life of the organ, system and body,” he explains. In addition, for cases with ischemia due to the horse’s inability to shift their weight from one limb to another, icing has a protective effect. The ice slurry cools the leg to a degree where blood vessels constrict, reducing the shower of inflammatory mediators to the foot. “There are cytokines that are important in inflammation,” says Dr. Orsini. “You’re reducing the mediators of inflammation and white blood cells being sent to the tissues and also reducing their metabolic requirements.” While cryotherapy is relatively simple and doesn’t require complex or expensive equipment, it must be performed properly and expeditiously in acute laminitis cases to be effective. “The use of cold therapy after the developmental phase has important function but not to the same degree as in the developmental phase,” adds Dr. Silverman.

NSAIDs

In the acute phase of laminitis, and while cryotherapy is being administered, other avenues are simultaneously being taken to control pain and inflammation. Veterinarians reach for NSAIDs as a proven means to impact both pain and inflammation. While NSAIDs can be extremely effective, they aren’t without side effects that can introduce complications to a laminitic patient. “You have to take the individual case into account,” says Dr. Byrne. “Does the horse have ulcers or a history of ulcers? That throws a wrench in the treatment plan,” she says of the difficulty in administering medication to ulcer-prone horses. “With most cases, it’s our first time seeing them. We’re putting in a catheter for DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) and administering phenylbutazone (Bute) to control the inflammation and pain. If we’re worried there’s other systemic things going on, we’ll use Banamine,” explains Dr. Byrne of her approach. Interestingly enough, Dr. Parks and his team at the University of Georgia have started to use Tylenol® with success. “The reason for using Tylenol® is that it’s a systemic medication that hopefully allows you to lower the doses of phenylbutazone,” says Dr. Parks. “The jury, however, is still out on how effective it is. Additionally, one of my colleagues here at the University of Georgia has done research on the use of hydromorphone. That is probably the narcotic of choice here right now,” he explains.

To Dr. Byrne, a key component of administering NSAIDs is simultaneously supporting the horse’s gut environment to get out in front of the threat of potentially damaging side effects. “You have to have some kind of gut protection involved,” agrees Dr. Silverman. “If the gut’s inflamed, the whole system is inflamed and angry and the horse isn’t utilizing the medication I’m administering like it should be. If I can optimize gut function, then I can often get better utilization. Bottom line, you have to pay attention to the function of the gut,” Dr. Silverman says firmly. Dr. Byrne has long been a proponent of considering the health and environment of the gut microbiome in the majority of her patients but especially those receiving NSAIDs for conditions such as laminitis. “We put many of these laminitic cases on Platinum Balance® to help maintain a normal, healthy gut microbiome, which has been proven to take a big hit with Bute. I like giving Balance because of its probiotics, prebiotics and glutamine,” adds Dr. Byrne of her whole horse approach to not only treating the pain and inflammation associated with laminitis but helping to support the gut environment through nutrition while treatment continues.

While NSAIDs are a critical tool in the acute phase, Dr. O’Grady takes a more conservative perspective on using these medications when assessing and treating patients that may be more chronic. “I don’t use a lot of medication,” says Dr. O’Grady of his approach. “If you have to use a big dose of medicine, then you’re either missing something with the feet or you’ve got severe pathology where you're not going to win,” he says plainly. “If you give that horse a lot of medicine to the point where you’re thinking he feels better, then he’s going to walk around more. He doesn’t have anything to hold his bone up except for compromised lamellae, so he’s going to make things worse,” explains Dr. O’Grady. “I don’t want the horse to be in pain, but I don’t mind a little discomfort so the horse will respect his feet, which makes the horse cautious and gives me a full understanding of what I’m dealing with,” he says, illustrating that he wants to know what the horse is feeling and would rather see them lay down than walk on feet that wouldn’t permit it without the aid of pain medication.

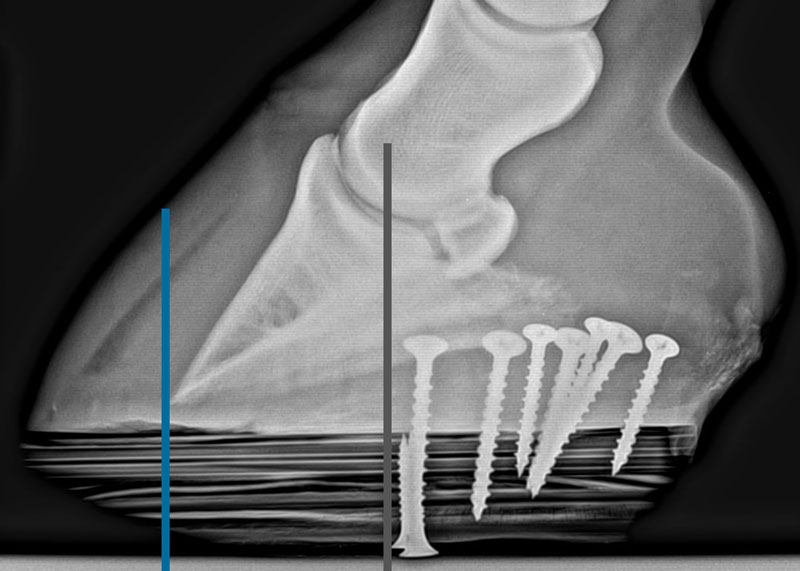

Wooden shoe applied to the foot. Note the beveled perimeter of the shoe and the point of breakover.

IMAGE COURTESY OF STEPHEN O'GRADY, DVM

Radiograph shows the biomechanics of the shoe. Gray line is center of rotation and blue line is point of breakover.

IMAGE COURTESY OF STEPHEN O'GRADY, DVM

“If the gut's inflamed, the whole system is inflamed and angry and the horse isn’t utilizing the medication I’m administering like it should be. If I can optimize gut function, then I can often get better utilization. Bottom line, you have to pay attention to the function of the gut.”

— Mark Silverman, DVM, MS

Sporthorse Veterinary Services

Therapeutic Farriery

While cryotherapy and the use of DMSO, NSAIDs, advanced nutrition and numerous other therapies are mainstays in the treatment of laminitis cases, skilled farriery plays a critical role in nearly every case outcome. “The equine foot is the one aspect of veterinary medicine that generally requires input from two professions, the veterinarian and the farrier,” says Dr. O’Grady. Veterinarians well-versed in treating laminitis cases will be the first to advocate for the importance of therapeutic farriery and maintaining a strong relationship with farriers that can offer experience and expertise. “We bring in therapeutic shoeing right away whenever possible,” says Dr. Byrne of her team’s approach to their laminitic patients. She’s seen the impact and considers the team of farriers that work closely with Alamo Pintado to be vital. Veterinarians like Drs. O’Grady, Lesser and Silverman have the advantage of being both skilled farriers and veterinarians with long experience behind them in the equine foot specifically. “When considering farriery, the term ‘foot support’ is often misconstrued when referring to acute or chronic laminitis,” says Dr. O’Grady. “At present, we have no physical means in which to counteract (or support) the weight of a horse on its feet.” There are, however, numerous shoeing methods and technologies that farriers reach for to support various laminitis cases. “There are a lot of options out there, from wedges to glue-on shoes, heart bar shoes to Soft-Ride Boots® and Ultimate Cuffs®, just to name a few,” says Dr. Lesser. The Ultimate Cuff® is a cuff-like wedge often used on rotational cases to help reduce the pull of the DDFT on the lamina. It’s a favorite of Dr. Lesser and his team. “There’s this certain way to apply it to get the correct mechanics. Obviously, applying the mechanics and the trim beforehand is the hardest part of all of this to make sure we have the optimal outcome. That’s why it’s so important to have that farrier relationship because without that, we’re not going to be successful as veterinarians,” says Dr. Lesser. “I don’t really care what tool is being used on the foot. It doesn’t matter as long as we’re trying to achieve the same mechanics,” Dr. Lesser insists.

Perhaps one of the most significant innovations in therapeutic farriery for laminitis cases is the wooden shoe. “I’ve had the most consistent success in 50 years with the wooden shoe,” says Dr. O’Grady, a worldwide authority on the wooden shoe. Dr. O’Grady maintains that there are three avenues to take with therapeutic shoeing in a laminitis case. “First, the biggest thing with the wooden shoe is that you take one flat piece of material, in this case wood, then put it on another flat surface, the bottom of the foot, and you redistribute the load across the whole bottom of the foot.” This allows the veterinarian and farrier to accomplish vital load redistribution that is hard to achieve with normal shoes alone or the combination of shoes and pads. After load redistribution, the second avenue available is seen in repositioning the breakover. Last up is adding heel elevation to compensate for the tension in the tendon, if necessary. “The wooden shoe does all three of these, plus more,” says Dr. O’Grady. “With the wooden shoe, the bevel that goes all of the way around doesn’t only take the torque off the lamina in the front, it also takes torque when the horse moves from side to side,” he points out. “This is termed ‘conformational breakover,’ ” he adds. “Is it 100 percent consistent? Absolutely not. There’s a big learning curve for putting them on, which includes the appropriate foot trim, proper size, fit and placement of the wooden shoe on the foot combined with the appropriate application.” Dr. O’Grady points out that while the wooden shoe has been a game-changer in managing acute and chronic laminitis cases in his hands, certain criteria need to apply in order for its successful use. He’s adamant about both case selection and technique. Dr. O’Grady’s determining questions include whether or not the horse has enough healthy tissue in its hoof capsule to rehabilitate. “If the answer is yes, then the wooden shoe is going to be beneficial,” he says. “If I don't have enough healthy tissue or the horse has severe rotation or sinking, then the wooden shoe just isn’t going to help.” It is always helpful to understand not only the biomechanics of the wooden shoe but also how they are thought to work. “As with any farriery method, it will only be effective if coupled with the appropriate trim,” reminds Dr. O’Grady.

With a variety of tools and experience in their arsenal, veterinarians use strategies that can take necessary shifts depending on if a they are dealing with a rotating horse or a case that is sinking. “There are only a few things we can do for horses that are rotating, but there are a lot of ways we can do them,” says Dr. Parks. His three main tactics include, one, changing the distribution of pressure across the bottom of the foot. “For instance, if an animal is very painful under the middle of its sole, you can shift weight-bearing to areas that don't hurt as much,” he says simply. “Second, we can change the moments about the DIP (distal interphalangeal joint).” In horses that rotate, the action of the dorsal lamellae is opposed by the deep digital flexor tendon. “We can decrease the tension of the deep digital flexor tendon by raising the heels or even cutting the tendon,” explains Dr. Parks. “Third, we can provide some cushion underneath the horse’s foot. If you can imagine, your foot hits the ground slower when you walk on something that compresses. Horses with rotation and painful soles benefit from decreasing the flexor movement and shifting their weight away from the sole. If they’re really sore, then we’ll place something that compresses underneath them, like the lining of a Soft-Ride Boot®, or an EVA (Equicast™ EVA/Wood Therapeutic Shoes),” he says. “Those are basically the three biggest things we can do,” Dr. Parks summarizes. How these approaches are executed depends on the severity of the lameness at hand and what type and level of displacement has occurred.

So-called “sinkers” are an entirely different case, requiring yet another approach and posing significantly greater challenges in most cases. “For horses sinking asymmetrically, you can shift the center of pressure away from the side that is sinking,” points out Dr. Parks. “You’ve got nothing to lose by improving breakover because that decreases the torque on the limb as the animal moves just as it lifts its heels up,” he says. Veterinarians undoubtedly consider sinking laminitis cases to be amongst the greatest challenges they encounter, depending on the owner’s goals for the outcome. “If they’re progressively sinking, they’re a real problem because there’s damage everywhere,” says Dr. Parks in earnest. “There’s no good thing about a horse with laminitis, but at least for horses that are rotating, you can use the back half of the foot. With a horse that’s sinking medially, you can use the lateral part of the foot somewhat. For a horse that’s sinking all of the way around, there’s no good piece of the foot left to use to assist in weight-baring.” It’s an unfortunate fact, but the success rate for horses that are actively sinking is extremely low.

Ultimately the one-two punch of a veterinarian wellversed in the foot, together with a skilled farrier, can directly impact the outcome of a laminitis case for the better, whether it be in a preventive and subclinical stage, a clinical and rotating patient or in certain classifications of sinkers. “Our potential for success will be a lot lower if we don’t actually address these cases mechanically by using both a veterinarian and a farrier working together,” says Dr. Lesser of the critical nature of the relationship and its impact on the odds for success.

Tenotomy

When alignment issues are unable to be resolved and there is significant damage at play, veterinarians can consider the option of a tenotomy. “Our indication for a tenotomy is that the horse is in unrelenting pain and not improving with other methods. Also, when the bone penetrates the bottom of the sole, it may be time to do a tenotomy,” says Dr. O’Grady of the criteria leading to the decision to perform a tenotomy. The procedure removes the force of the tendon off the bone, allowing the farrier to then realign the bone to the ground. “We anesthetize the patient a bit below the knee with local anesthesia, then make a small wound just over the DDFT right in the middle of the leg,” details Dr. O’Grady. “We have two little surgical loops that go in there and we turn the tendon outwards to the skin surface, and then we transect it there,” he continues. “Before we do that, we have a shoe on there that prevents the toe of the horse’s foot from flipping upwards when he lands on the ground.” It’s considered a simple procedure that can be surprisingly effective.

Preventive Strategies

With a disease like laminitis, the ultimate successful outcome occurs when the disease itself can be avoided rather than treated. “You’re not going to ever reach a cure for laminitis. It’s all about prevention,” says Dr. O’Grady matter-of-factly. Dr. Parks agrees and goes a step further in terms of the importance of prevention. “There are two aspects to it,” he explains. “One is prevention and the other is treatment of the early disease process. If we aren’t successful, then we’re dealing with the consequences.” It’s a fact Dr. Silverman echoes, “You’re better off avoiding a battle than going to battle, and that battle is all uphill.”

In the preventive realm, it appears that horses with metabolic disorders are at a heightened risk for laminitis. “I think studying the epidemiology of EMS is going to yield the best preventive results,” says Dr. Parks. In his practice, Dr. Lesser has learned through years of experience that it falls on the shoulders of the equine veterinarian to aggressively steward a patient’s nutrition and weight to avoid metabolic disorders. “For a lot of these horses that are borderline metabolic, I would encourage veterinarians to be a bit more aggressive with them,” he says. Dr. Silverman too has long been a proponent of managing a patient’s nutrition regimen and weight to avoid the pitfalls of both metabolic disorders and the downhill consequences of those conditions, namely laminitis. “Don’t be afraid to comment on that hunter in front of you that may be a little full-figured. We as veterinarians need to be in the feed room, we need to be familiar with the diet, and we need to know if this horse is being given 12 different products that may not be meant to be mixed together,” he says frankly. “We have to get more aggressive about looking at the whole picture. ‘Wait and see’ should never be our approach as veterinarians in these cases. We have to get in there and make the required changes to give this horse the best chance at success,” says Dr. Silverman.

For those horses at risk for laminitis, taking steps to identify the disease state in a subclinical phase could mean the difference between maintaining the horse’s longevity and a potentially serious clinical battle. Aside from recommending that atrisk horses have a metabolic workup, Dr. Lesser is an advocate of early radiographs to establish a baseline. “A lot of owners are willing to take some baseline radiographs of the horse’s feet,” says Dr. Lesser. “That will give us a lot of information. A good farrier can take that information and make the appropriate changes to help that horse with either a little bit of mechanics support, blood supply or protection from bruising on the bottom of the foot.”

Laminitis seems to be a disease best fought prior to the disease state itself. While tremendous progress has been made with diagnostics, cryotherapy, analgesia and therapeutic shoeing, catching the condition in a subclinical state is imperative to long-term success. Regardless, veterinarians are now armed with the perspective that they are not simply treating disease, but rather, they are treating an animal comprised of trillions of cells and a collection of interconnected systems that have a direct cause and effect with one another. In other words, viewing the horse as a whole animal and treating beyond the disease itself is the way of the future and where significant progress is being seen. “It is important to look at the whole animal as well as the feet,” says Dr. Parks of his approach and support for practicing so-called “wholehorse medicine.” Dr. Silverman agrees, “When I look at a horse, I go from the ground up,” he says. “I want to see how the horse is being ridden, trained and shod. This lets me get a better idea of the whole picture, and, as veterinarians, we have to take every aspect into account. The only way you survive these cases is by looking at the whole picture.”

Dr. Stephen O’Grady, veterinarian and expert farrier, examines a horse’s hoof after the application of a Heart Bar shoe.

IMAGE COURTESY OF STEPHEN O'GRADY, DVM

“The general goal is to reduce or eliminate feeds that could precipitate a laminitis episode. This would include reducing the intake of nonstructural carbohydrates (starch and a variety of sugars) from pasture, forage, and from grain and commercial feeds that contain a high concentration of grain. Also, be sure the horse is not being fed extra sugar or starch in their treats.”

— Meri Stratton-Phelps, DVM, MPVM, DACVIM, (LAIM), DACVN

Equine Clinical Nutritionist, Platinum Performance®

Nutrition

“I get really aggressive nutrition-wise,” says Dr. Lesser. With the ability to influence both cellular health and function, nutrition can be a vital piece of the equation in both a preventive and therapeutic scenario for laminitis patients, and certainly an important piece of the “whole-horse” approach. “We’re individualizing our approach to meet the horse’s nutritional demands for healing,” adds Dr. Orsini of his thinking when feeding and supplementing his patients at New Bolton Center.

There’s both a science and an art to managing the nutrition regimen for active laminitis cases. “The general goal is to reduce or eliminate feeds that could precipitate a laminitis episode,” explains Dr. Stratton-Phelps, an expert in advanced nutrition as it pertains to laminitic patients. “This would include reducing the intake of nonstructural carbohydrates (starch and a variety of sugars) from pasture, forage, and from grain and commercial feeds that contain a high concentration of grain. Also, be sure the horse is not being fed extra sugar or starch in their treats.” While nutritional management can undoubtedly help support sepsis-related and support-limb laminitis cases, the most marked changes can be seen in endocrinopathic laminitis patients. “We’re dealing with carbohydrate overload here, and during an acute case of endocrine-based laminitis, we have to eliminate the source of the trigger,” says Dr. Silverman. Dr. Lesser agrees that dietary intervention, coupled with front-line medical treatment to prevent further damage, is paramount in these cases. “I start by cutting their grain or removing it completely, depending on the case,” explains Dr. Lesser. “If we’re worried about underlying metabolic conditions, we take them off of grass as well.” Like Dr. Lesser, Dr. Byrne’s team at Alamo Pintado follows suit, eliminating excess starches and sugars from the diet. “We soak their hay for an hour and let it drain, with much of the sugar draining out with the water,” adds Dr. Byrne.

Excess weight is an obvious key player in endocrinopathic laminitis cases or at-risk cases that are overweight with signs of a looming metabolic disorder. “Horses with laminitis and EMS may need to have restricted access to pasture or be completely removed from pasture,” points out Dr. Stratton-Phelps. Slow feeder devices and grazing muzzles can be used under the guidance of the veterinarian and may be helpful tools to reduce the rate of feed intake. “We feed more continuously and in smaller quantities, oftentimes through a net,” confirms Dr. Byrne. “We also put these horses on Platinum Performance ® Equine to provide the vitamins, minerals, omega- 3s and antioxidants the horse needs, especially since we’re soaking and draining the hay which reduces many of these nutrients,” adds Dr. Byrne. Dr. Stratton-Phelps agrees that “omega-3 essential fatty acids support a normal inflammatory response, as have more novel ingredients such as pterostilbene.” Dr. Byrne and her team also often turn to additional formulas as part of their protocol. “We’ll sometimes use Platinum’s Healthy Weight oil as a source of healthy calories by way of omega-3 fatty acids, and I like this oil’s vitamin E content as well. Past that, we’ll often administer Hemo-Flo® and Platinum Hoof Support to support normal circulation and hoof growth,” she adds.

While advanced nutrition can help support the horse systemically, in addition to specific targets, an area of vital importance in laminitis patients is the equine gut microbiome. A hot topic in the last several years, the microbiome can have a deep impact on the overall health of the horse and can take a punishing blow when the animal is introduced to antibiotics, NSAIDs and various medical therapies, especially during a catastrophic laminitis episode. “One of the treatment goals is thinking about the holistic approach and the needs of the whole horse. Their intestinal tract in particular is at risk of having its own set of problems, namely colic,” says Dr. Orsini, referring to horses being treated for laminitis. “I’m a firm believer that we need to protect the gut as we’re treating the disease at hand,” adds Dr. Lesser. “The vast majority of my cases are now fed Platinum Balance daily, and they’re also on omeprazole for stomach ulcers,” he continues. “It’s horrible when you have a laminitis case and they colic from the NSAIDs or suddenly you’ve got colitis on your hands due to either NSAIDs or antibiotics. You have to keep the gut in mind when treating these patients, no question about it.”

While many veterinarians appreciate that dietary changes must be made during a laminitic episode, the profession has seen an uptick in the use of advanced nutrition as a complementary therapy that stands beside medical intervention to give these patients the best possible outcome. “Yes, we must focus on the injury,” says Dr. Silverman. “But we can’t forget the rest of the animal. We can’t forget to think about nutrition and what it can do.”

The Hard Call

It’s an uncomfortable conversation and one that no veterinarian or horse owner wants to have, but being clear with both the end goal and the contingency plan in case that goal can’t be met is key in the beginning stages of treating any laminitis case. “As veterinarians, we need to make sure the client has the right goal in mind for the horse,” says Dr. Silverman. “If their only goal is to return the horse to full performance, then there’s a good chance we’re looking at the wrong goal in terms of what may be possible and right for the horse. However, if our goal is to get this horse comfortable and to give him a life that he’s earned, then we’re on the same page,” he says. “All parties need to have well-established expectations early on, and they have to be clarified so we can reach a level of success that’s respectful of the horse and the enormous emotional and financial input these cases require.”

Like so many veterinarians, Dr. Silverman lets the horse and the individual dynamics of the case lead his recommendation on whether or not to proceed. “For me, the decision is based largely on the horse itself and doing everything I can to make sure they don’t suffer,” he says. “I am not a person who believes that we as veterinarians treat these cases because we can. We should be doing it because it’s the right thing to do for that case. There are times when the right thing to do is to let the horse go.” No horse owner, or veterinarian for that matter, wants to make the hard call. However, when laminitis is at play, sometimes that call is ultimately what’s right for the animal when it is decided that, despite treatment and every effort, the horse will not be comfortable or able to live a quality life.

The lateral, dorsopalmar and solar radiographic views of the venogram show the areas of the foot where the circulation can be assessed.

IMAGE COURTESY OF MARK SILVERMAN, DVM

“There’s work being done on viral vectors, a genetic material delivery system, along with gene therapy, which could prove to be an important advancement. It could tell us why one horse that’s 300 pounds overweight is out on rich green grass and never founders while another is barely overweight and does. If we can come up with some type of gene therapy, it could change things dramatically.”

— Erin Byrne, DVM, DACVIM

Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center

Emerging Research

One of the challenges of laminitis is the dichotomy of where we are in terms of research. We know there is so much we don’t know, but, at the same time, we’re dealing with a disease state that is incredibly difficult to study. “There’s a lot of basic research that needs to be done,” says Dr. Lesser. “What I need as a practitioner is something that is truly clinically applicable and could help us with our treatments.” The difficulty in properly studying laminitis to provide those clinical solutions is a constant frustration to veterinarians both in academia and in the field. “One of the problems is, how do you study laminitis?” asks Dr. O’Grady. “How many laminitis cases are the same?” To create a valid study model, horses would need to be of the same relative age and health status, perhaps the same discipline and environment, have the same foot conformation and experience the same or a similar trigger that led them into a laminitic state. The moral of the story is, veterinary medicine hasn’t figured out the model yet.”

While there are obvious challenges in designing research studies to yield reliable results, there are important theories at work that warrant further exploration. “There’s work being done on viral vectors, a genetic material delivery system, along with gene therapy, which could prove to be an important advancement,” says Dr. Byrne. “It could tell us why one horse that’s 300 pounds overweight is out on rich green grass and never founders while another is barely overweight and does. If we can come up with some type of gene therapy, it could change things dramatically,” Dr. Byrne says with hope. Dr. Orsini seconds Dr. Byrne’s sentiments in terms of creating tools that can help identify horses at a greater risk for laminitis and pave the way for early treatments to avoid the disease. “If we can identify the horses at a greater risk for the disease early on, then we can target our therapies and our preventive measures accordingly. That way, you're using your resources more strategically for those that need it most,” he says.

One area that Dr. Orsini is hoping to explore further is the use of regional perfusion with specific and potent drugs to reduce the inflammatory events that lead to failure of the supporting structure of the coffin bone, resulting in laminitis. Veterinarians can infuse life-saving drugs to the distal part of the limb in higher concentrations and reduce the risks of an adverse systemic event. Theoretically, reducing the risk of adverse events by administering these ‘drugs’ locally should equal better prevention and outcome for this crippling and life-threatening equine disease. “We know that interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a very important component of inflammation. If you specifically target these inflammatory mediators with IL-6 antagonists, it could positively impact our ability to prevent and treat acute laminitis,” explains Dr. Orsini.

“The horse’s foot is genuinely fascinating. That's the bottom line. If something is that fascinating, we should be spending time thinking about it and studying it.”

— Andrew Parks, MA, Vet MB, MRCVS, DACVS

Department Head, Olive K. Britt & Paul E. Hoffman Professor, University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine

Looking Ahead

While laminitis remains a devastating disease with no turn-key solution for consistent results, veterinary medicine has also progressed its understanding and approach to treatment significantly in the last several decades. Afflicted horses now have a fighting chance, and through experience, veterinarians now have a stronger grasp of the risk factors, triggers, symptomology and treatments that can impact patient outcomes. Thanks to veterinarians that perform double duty as skilled farriers and proponents of the equine foot, we now also have a significantly more advanced appreciation for the structure and value of the foot’s role in the overall health and function of the horse. “The horse’s foot is genuinely fascinating. That's the bottom line. If something is that fascinating, we should be spending time thinking about it and studying it,” insists Dr. Parks. His friend and colleague Dr. O’Grady certainly agrees. “We have to educate veterinarians as farriers and educate farriers as veterinarians,” he says of the necessary two-way exchange of information to truly move the needle on laminitis. It’s that passion as an educator that has led the profession to overwhelmingly choose Dr. O’Grady as the 2020 honoree for the AAEP Distinguished Educator Award. “I didn’t know anything about it,” Dr. O’Grady says of his surprise. “It’s humbling to say the least.”

It’s in the spirit of moving the profession forward through discovery, both in academia and the field, that inspires many veterinarians to look deeper. “Horses are our best teachers should we choose to listen to them. With experience, we learn that they don’t follow our preconceived notions as we’re treating them,” says Dr. Parks. It’s that challenge that sparks a fire in the belly of equine veterinarians to not only do better but to delve into uncharted territory to find improved preventive measures and treatments that may not have been tried before. “I love the challenge, and I love the unknown. That’s what does it for me,” adds Dr. Lesser. “In the end, I was going to work with horses no matter what, but the foot is where I found my place, and it gave me a way to make a difference and stay on the cutting edge of what’s possible.” Dr. Orsini agrees, after years studying laminitis and working to uncover new methods of treatment. “As veterinarians, we value science and solving problems, of course, but it’s also our ability to improve the health and welfare of the animals we take care of and the lives of the people who love them,” he says sincerely. Just the latest addition to add to his life’s work on the subject will be his forthcoming book entitled, Comparative Veterinary Anatomy: A Clinical Approach. Together through the book, Dr. Orsini and his two co-editors deliver a master class on clinical anatomy using a case-based approach. They detail the workup, diagnosis and treatment plan of the case before delving into the important anatomy based on each specific case and how to link basic anatomy to clinical anatomy. He hopes the unique way in which the book is written will give veterinary students and colleagues a more solid footing in fully learning and understanding anatomy, resulting in better clinicians, veterinarians and surgeons.

While laminitis can be a deeply emotional journey for the horse owner and a life and death challenge for the horse, veterinarians and their support teams give everything they have to each case, relying not only on the research but on collaboration with each other, close communication with skilled farriers and colleagues and an utter determination to keep the horse’s comfort and quality of life firmly in their sites. Put simply, it’s a passion and the stakes are firmly understood. “I guess what keeps me going is being fair to the horse,” says Dr. Silverman honestly. “As veterinarians, that’s what’s on our minds more than anything.”

Featured Veterinarians

Stephen O’Grady, DVM, MRCVS

Virginia Therapeutic Farriery

Craig Lesser, DVM, CF

Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital

Mark Silverman, DVM, MS

Sporthorse Veterinary Services

Erin Byrne, DVM, DACVIM

Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center

Andrew Parks, MA, Vet MB, MRCVS, DACVS

Department Head, Olive K. Britt & Paul E. Hoffman Professor; University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine

James Orsini, DVM, DACVS

Associate Professor of Surgery and Former Director of the Laminitis Institute; New Bolton Center, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

Meri Stratton-Phelps, DVM, MPVM, DACVIM, (LAIM), DACVN

Equine Clinical Nutritionist, Platinum Performance®

by Jessie Bengoa,

Platinum Performance®