Helpful or Detrimental?

While a Necessary Part of The Body's Natural Healing Process, Chronic Inflammation can Contribute to Various Disease States; Diet can Make an Impact

Inflammation is a constant. It is the body’s natural response to injury, irritation or infection and is required for cellular regeneration. When we see or feel its symptoms in our horses — redness, swelling, heat, pain and loss of tissue function — a typical reaction is to get rid of inflammation as soon as possible. However, inflammation is an essential part of the innate defense mechanism and a critical part of the body’s natural healing process.

There are two distinct types of inflammatory responses: acute and chronic inflammation. When working properly, acute inflammation is a good thing and critical for survival. It protects from infection and injury and removes damaged cells and tissues to promote healing. However, too much inflammation for too long is harmful. When the body’s natural protective response is turned on and cannot be shut off, the persistent and excessive inflammatory response can cause cellular destruction and irreversible tissue damage. This chronic inflammation is a component of many equine disease states. Lessening chronic inflammation has major health benefits. Achieving this through the daily diet is a simple way to support the health of every horse.

PHOTO BY ELIZABETH HAY PHOTOGRAPHY

Types of Inflammatory Responses:

- Acute inflammation - When working properly, it is a good thing and critical for survival. It protects from infection and injury and removes damaged cells and tissues to promote healing.

- Chronic inflammation - Too much inflammation for too long is harmful. When the body’s natural protective response is turned on and cannot be shut off, the persistent and excessive inflammatory response can cause cellular destruction and irreversible tissue damage. This chronic inflammation is a component of many equine disease states.

Helpful Inflammation: The Acute Inflammatory Response

Acute inflammation is the short-term response to injury or trauma by the equine immune system. Pathogens, disease- causing microbes such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa or fungi, are common inflammation stimuli. A foreign body or toxic substance will also elicit an inflammatory response. This type of inflammation has a rapid onset, within seconds, and often resolves within a few days.

Your horse is kicked by a pasture mate during turnout and suffers a shoulder cut. What happens? The immune system’s first line of defense, the physical barrier of the skin, is compromised. Injured or dying cells release several specific enzymes and proteins including histamine, serotonin, prostaglandins and kinins, like bradykinin that is heavily involved in pain. Multiple inflammatory cytokines, or signaling molecules, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), interferon gamma (INF-gamma) and an array of interleukins (ILs) are secreted in response to infection, injury or trauma. These pro-inflammatory chemical messengers wave a type of internal red flag that immune cells are needed to eliminate the cause of the inflammation and initiate healing.

The innate, non-specific immune system that guards against threats entering the body activates and instantaneously sets off the inflammatory response circulating white blood cells called leukocytes to surround and protect the injury site. These white blood cells are the special forces of the immune system and begin cellular carnage cleanup and start the regeneration process.

Special Forces: White Blood Cells and Immunity

There are five classes of leukocytes in the immune system armory: neutrophils, basophils, monocytes, eosinophils and lymphocytes.

Neutrophils are the immune system’s first responders. These are the “work horses” of the immune system. Neutrophils are recruited to disinfect and kill infectious agents as well as clean up cellular debris. While they are quick to respond, neutrophils lack specialization and die relatively quickly. However, as they make up 60-70% of the total white blood cell population, they are effective in sheer numbers.

Basophils make up a very small percentage — under 1% — of total white blood cells. However, their job is not any less critical. They are chiefly responsible for initiating and promoting the inflammatory response, particularly the allergic response, by releasing the chemicals histamine and heparin created by the immune system.

White blood cells consist of 1-6% monocytes that are split into two types in horses: dendritic cells and macrophages. Dendritic cells identify pathogens and send signals to specialist cells. Slower to arrive to the action but longer lasting, macrophages help repair injuries and are specialized in the seek-and-destroy response to foreign bodies. Macrophages are relatively large cells and, along with neutrophils, are capable of phagocytosis that, like Pac-Man, removes bacterial and fungal pathogens by consuming them. They recognize, engulf and destroy infected or damaged cells.

Pest specialists, eosinophils make up approximately 1-3% of white blood cells. They fight infections most often caused by parasites, especially helminths, or parasitic worms, and fungus. They also increase with inflammation of the intestines, lungs and skin, and are prominent in allergic reactions.

Lastly, lymphocytes, the true immune superheroes, make up 20-40% of all white blood cells. These cells provide the adaptive immune response and are the slowest to respond, showing up if the previous defense efforts fail. Lymphocytes target specific pathogens including foreign bacteria, viruses and fungi. There are two main distinct lymphocyte cell types — B cells and T cells — that work together and are cumulatively responsible for antibody production, direct cell-mediated killing of virus-infected cells and bacteria, and regulation of the immune response.

B cells, or B lymphocytes, are the muscle behind antibody-driven immunity. B cells make specialized proteins called antibodies that create a tailored response to fight the infection. The antibodies bind to invading pathogens to neutralize or destroy them, preventing the pathogen from invading a normal cell and causing infection or damage. Antibody production can continue for several days up to months until the pathogen is overwhelmed. B cells can also recruit other cells to help destroy infected cells.

There are multiple specialized types of T cells, or T lymphocytes, that provide adaptive, cell-mediated immunity by directly targeting, attaching and killing infected cells, foreign substances or other noxious microorganisms such as viruses and unwanted bacteria. T cells help regulate the immune system to prevent and avoid an overreaction that can cause the body harm, as seen in autoimmune diseases. T cells can destroy the body’s own cells that have been taken over. T cells produce cytokines that help trigger other parts of the immune system such as macrophages to remove invaders and dead tissue.

B cells and T cells can become memory cells — capable of recognizing, remembering and responding to antigens from a prior infection. An antigen is a foreign substance, usually a protein, that is found on the surface of a pathogen and stimulates an immune response. If re-exposed, memory cells will initiate a quick and strong immune defense. This is known as specific immunity or acquired immunity, and while it takes time to build and improve, this action of “remembering” foreign substances is essentially how vaccinations prevent certain diseases. Vaccines prime the immune system by exposing lymphocytes to antigens on the infectious pathogen, readying the immune response to react quickly should it be needed.

As the entire white blood cell network is working, enzymes and cytokines signal for additional white blood cells to respond. The release of these substances at the site of the injury results in the five symptoms of acute inflammation: redness, heat, swelling, pain and loss of function (stiffness and immobility). With the migration of white blood cells to the injury, the blood vessels leading to the site become leaky to allow for the influx of cells to get to the injury. This blood vessel permeability is the source for the fluid buildup that causes swelling, which also contributes to the heat, redness and pain at the injury site. These can lead to a temporary loss of function in the area as a protective mechanism.

All of these reactions are necessary to protect the body from further injury, to clean the site from dying tissue, to promote healing and return to normal function. Once the initial response is quelled, the body can move into the next phases of repair and regeneration. Acute inflammatory treatment often includes rest, ice, wound care and may require medical intervention from a veterinarian. The inflammation cycle is normal and healthy and helps to keep horses alive and responsive to injuries or illnesses in their body.

Ongoing State of Emergency: Chronic Inflammation

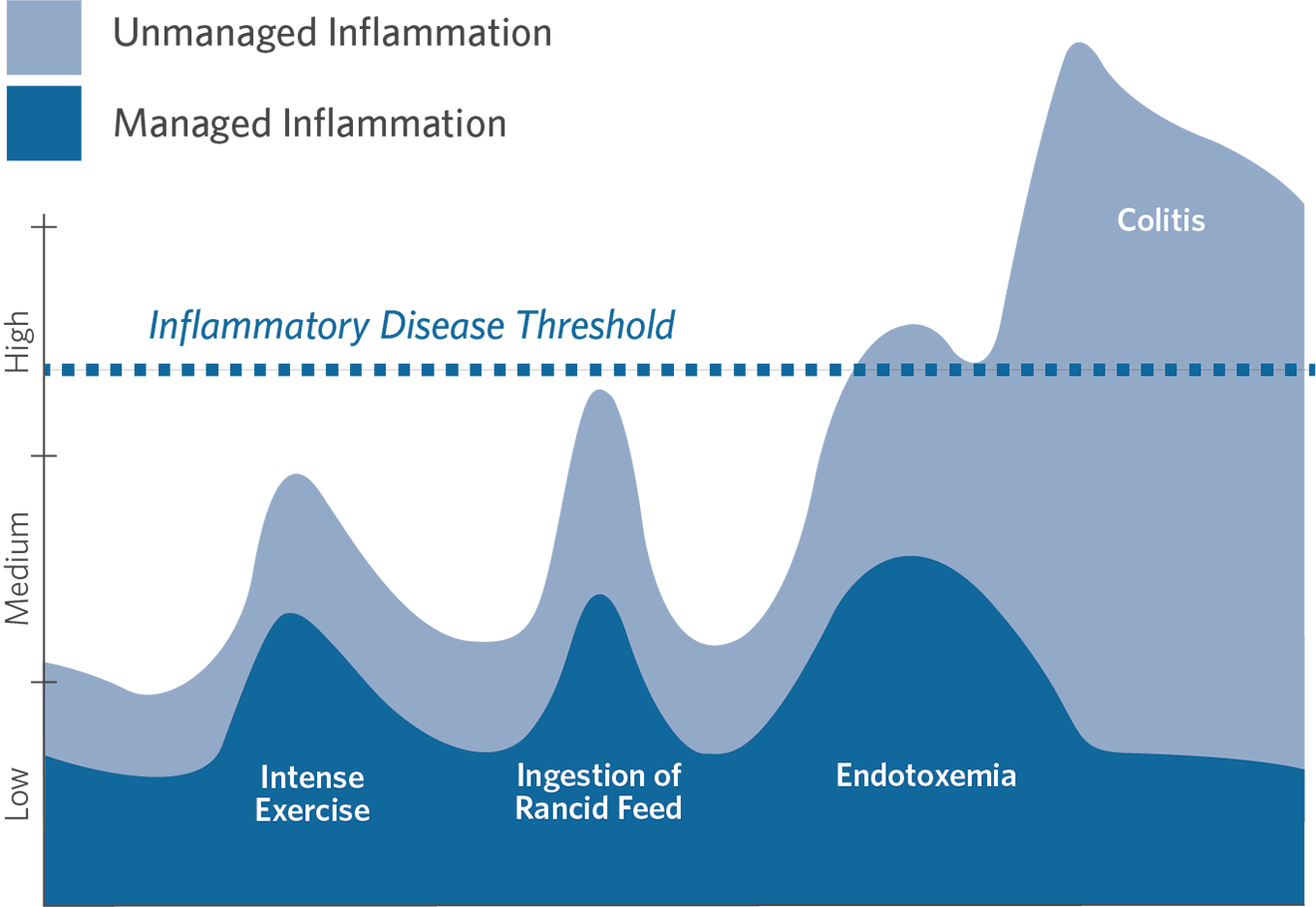

Inflammation is clearly necessary but too much for too long can have significant repercussions. With chronic inflammation, there is continued, persistent or overexpression of the inflammatory responses. The body essentially considers itself under constant attack, and the chronically confused immune system remains in an ongoing emergency state. The immune system keeps pumping out its chemical messengers that signal action is required.

Too many white blood cell defenders, body’s short-term heroes, continue to arrive to address the problem and may attack healthy cells and tissues in the chaos causing serious health ramifications. The chemical mediators of long-term inflammation result in cellular damage, contribute to poor recovery from injuries or surgery, cause excess pain and can result in lasting damage to the tissues and major organs. If the stimulus causing the inflammation persists, the inflammatory process becomes uncontrollable. What may have started in a specific tissue area releases substances into circulation that can affect the animal systemically and the extent of the damage worsens.

There is an irrefutable connection between long-term inflammation and disease. Chronic inflammation or hyperinflammation is involved in arthritis and joint disease, obesity, insulin resistance, colitis, leaky gut syndrome, equine metabolic syndrome, Cushing’s disease, laminitis, allergies, pulmonary disorders, equine asthma and more. If there is a disease state, there is likely chronic inflammation. Diseases in which inflammation plays a dominant role often carry the suffix “-itis.”

Chronic inflammation comes on slowly, sometimes taking weeks that extend into months or years. The classical signs and symptoms are subtler and can go undetected, particularly at the beginning before an actual disease state develops. It can be brought on by a number of factors including chronic illness or autoimmune conditions, chronic stress, long-term exposure to toxins or pollutants, physical inactivity and weight gain and feeding choices. If suspected and to get a better gauge of inflammatory levels, veterinarians may check the blood or plasma for inflammatory markers such as white blood cell count, fibrinogen concentrations, albumin/ globulin ratio and serum amyloid A (SAA). To combat this type of inflammation, several modalities may be used to intervene and attempt to shut down the inflammatory cascade including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or the use of corticosteroid injections for a specific joint, etc.

While the use of cortisone shots and NSAIDs provides essential clinical benefits, both classes of medications have potentially serious side effects. Besides the known risks associated with NSAIDs of gastric ulceration, colitis and leaky gut syndrome, both treatments suppress important parts of the immune system that are essential for healing and recovery. Not to mention that the use of corticosteroids can lead to a decreased ability to fight infection. For this reason, the best way to think of a healthy immune system is one that is in balance: not completely turned off and not excessively ramped up.

PHOTO BY ELIZABETH HAY PHOTOGRAPHY

An Equine Diet High in Omega-6 Fatty Acids

BASED ON HYPOTHETICAL DATA

Feeding the Flame

Managing normal levels of inflammation through the use of nutrition is a non-invasive and powerful way to promote health and long-term wellness. The overall balance of the equine diet is critical because, unlike humans, what horses are fed day-to-day stays relatively consistent. For example, you might have an extra piece of birthday cake one day, but salads the next. Some days are more nutrient-dense than others. Conversely, horses are likely to remain on the same feeding program for months or years unless there is a reason or need to change it. Because of this, the equine diet can readily impact normal levels of inflammation.

While some horses have access to fresh grass, a typical modern equine diet may include a combination of forage, cereal grains, grain-based commercial feeds or concentrates. The equine digestive system cannot support a diet high in grain intake. Cereal grains — corn, oats, barley and wheat — and grain-based feeds provide an excessive amount of sugar or starch, and an unhealthy ratio of essential fatty acids. High-grain diets are associated with colic, diarrhea, gastric ulcers, developmental orthopedic diseases, allergies, laminitis, obesity and insulin resistance.

Sugar (glucose) and starch (a long-chain sugar molecule) are common dietary carbohydrates used for energy. In equine nutrition, sugar and starch combined are known as non-structural carbohydrates (NSC). Sweet feeds containing high levels of sweeteners like molasses, as well as cereal grains, all contain elevated NSC levels. These types of feeds should be fed minimally to any horse. Even horses with high metabolisms or some equine athletes that may need extra calories to support body condition or activity level thrive when dietary sugar and starch is minimized and calories are provided from digestible energy sources, like beet pulp, and healthy fats. Several animal studies show that diets containing elevated NSC levels are linked with obesity, insulin dysregulation, oxidative stress, increased gut permeability and chronic inflammation.

Obesity promotes inflammation. An equine diet that is rich in non-structural carbohydrates can cause weight gain and obesity, particularly when fed to sedentary horses. Obesity is not just a problem for humans, recent estimates suggest that one out of every two domestic horses is overweight and more than one in five — 20-30% — is considered obese (having a body condition score greater than or equal to 7 out of 9). Adipose (fat) is an energy storage tissue, but it is also a very active, hormone-producing organ. Excessive accumulation of adipose tissue is associated with low-grade chronic inflammation. It is suggested that certain fat cells may produce cortisol and other hormones that interfere with the actions of insulin, the hormone that regulates sugar metabolism. Research shows obese horses secrete more pro-inflammatory mediators including cytokines and adipokines (a hormone produced by adipose tissue) that may contribute to the development of obesity-related inflammatory disorders such as insulin dysregulation and equine metabolic syndrome.

When sugar is digested, blood glucose levels increase rapidly. The pancreas responds by producing insulin that normally takes glucose from circulation to be stored in skeletal muscle, liver and adipose cells as glycogen. When the system is compromised, like in insulin dysregulation, cells are less able to respond to insulin. Insulin is produced in higher quantities to clear the circulating glucose, but the cells are resistant to the effects of insulin. TNF-alpha initiates insulin resistance which, interestingly, can be beneficial in certain states of illness as it ensures that glucose is circulating and available for critical organs that need it for survival, like the brain. The body unfortunately does not differentiate between when it is released as a survival mechanism or due to a high-sugar diet or obesity. The more sugar that is consumed, the greater the inflammatory response. Over time, high-sugar intake leads to a chronic increase in the circulating number of pro-inflammatory cytokines and a general pro-inflammatory state. Elevated insulin levels increase inflammation and, inflammation increases insulin.

In addition to cytokines, hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) causes the body to generate inflammatory reactive oxygen species or free radicals due to glucose being highly reactive with oxygen. Excessive levels of these volatile and destructive molecules damage cells and tissues and can lead to oxidative stress also provoking an inflammatory response.

Inflammation also disrupts gut health. The hindgut of the horse, or large intestine, which includes the cecum and colon — is essential to the function of the animal’s overall digestive system and is important for its thriving microbiome of beneficial bacteria, protozoa and fungi that are responsible for fiber digestion, a significant source of energy for the horse. These microbes greatly influence digestion — and also immune health, as more than 70% of the immune system resides in the gut. Starch and sugar are normally broken down in the small intestine and rapidly sent into the bloodstream. If too much starch is fed, especially at one time, such as in a meal setting, the undigested starch can spill into the hindgut where it will be subjected to microbial fermentation. The byproducts of this are acidic and will lower the pH of the cecum (cecal acidosis) and release pro-inflammatory cytokines. High sugar diets can also lead to increased intestinal permeability, known as leaky gut syndrome. The intestinal lining that normally absorbs digested food particles and serves as a selective barrier to pathogens becomes impaired, allowing bacteria and toxins to slip through the damaged intestinal wall and move into the bloodstream. The confused immune system aggressively attacks these escaped pathogens that can lead to systemic inflammation.

“Inflamm-aging”

“Inflamm-aging” is known as age-related chronic inflammation closely related to an overabundance of free radicals or oxidative stress. Simply getting older is a factor in both chronic inflammation and free radical accumulation that may contribute to the development of certain age-associated diseases in horses like in other species. Excess free radicals cause damage to cells and increase inflammation. An increase in circulating inflammatory cytokines can influence the competence of the immune system. Weakened immunity, even in outwardly- healthy horses, can make a senior animal more susceptible to infections and certain age related health issues such as muscle wasting, equine Cushing’s disease and chronic laminitis. Respiratory and skin allergies, as well as abscesses are indicators that the immune system may require extra support.

Stress reduction, low-impact exercise and a diet rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fats can help to support an aging immune system. General dietary guidance to support senior health helps keep their immune system prepared at all times by feeding a forage-based, balanced diet that supplies minimal sugar with specific ingredients including omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, like vitamins C and E, probiotics and joint-supporting nutrients.

Omega-3 to Omega-6 Fatty Acid Ratio

NATURAL GRAZING DIET

TYPICAL MODERN DIET

Inflammation is also affected by the presence and ratio of fatty acids in the diet. In the natural grazing diet of the horse, the ratio is about 5:1 omega-3 fats to omega- 6 fats in pasture grasses. Essential fatty acids are a small but mighty component of the natural grazing diet of the horse. Both omega-3 and omega-6 are considered essential because the horse lacks the enzymes for desaturation and cannot make them internally, so they must be included in the daily diet. Both types of essential fats are required and provide a wide variety of health benefits. Omega-6 fatty acids are involved with the production of eicosanoids and prostaglandins. Excessive levels of these biological mediators are correlated with chronic inflammation, cellular damage, longer healing times and several disease states. For horses, the natural forage diet often contains an adequate concentration of omega-6 fatty acids and supplements are rarely needed.

Common feeding practices that include grains and grain-based concentrated feeds have caused a widespread inverse essential fat ratio, drastically increasing the concentration of omega-6 fats in the diet and decreasing the total amount of omega-3 fats. It has been estimated that the typical diet of the horse today provides up to 18 times more omega-6 than omega-3 fatty acids, and likely higher.

Oils that are often fed to promote weight gain and shiny coats need to be taken into consideration as they are capable of providing excessive amounts of omega- 6 fats. Particularly when being given for weight gain, commonly-used corn oil may actually be working against the desired outcome as it contains approximately 55 times the amount of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids potentially creating inflammation in the digestive tract that may limit feed efficiency. Soybean oil, often labeled as vegetable oil and added to many commercial feeds, contains some omega-3 fatty acids, but it is much higher in omega-6 fatty acids with approximately 50% coming from linoleic acid. Flaxseed oil is rich in omega- 3 fats and offers a much healthier fatty acid profile, making it a good alternative to supply a healthy source of calories.

PHOTO BY ELIZABETH HAY PHOTOGRAPHY

In equine nutrition, sugar and starch combined are known as non-structural carbohydrates (NSC). Several animal studies show that diets containing elevated NSC levels are linked with obesity, insulin dysregulation, oxidative stress, increased gut permeability and chronic inflammation.

PHOTO BY SHANNON BRINKMAN

When working properly, acute inflammation is a good thing and critical for survival. However, too much inflammation for too long is harmful. Chronic inflammation is a component of many equine disease states.

Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

Oxidation is a normal part of everyday metabolism that allows the horse to utilize feedstuffs to turn what they eat into energy. Even though it is critical to life and biologically normal, oxidation produces a noxious side effect — reactive oxygen species. A few well-known ROS include peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical and singlet oxygen. Elevated levels of these free radicals are produced as a result of exercise, from inhaling air pollutants, ingestion of rancid feeds, a deficiency of endogenous antioxidants — products of the body’s metabolism — and through the exposure to ultraviolet light. Free radicals can also become excessive following injury or disease.

Free radicals are unstable atoms that have at least one unpaired electron in their structure and search to stabilize themselves, causing chaos in doing so. Once formed, these reactive radicals can initiate chain reactions resulting in a havoc-wreaking ripple effect on many other molecules within cells and cell walls. They damage the phospholipid layer around cells and cell organelles, can also destroy enzymes and damage DNA and other cellular proteins. If left uncontrolled, free radicals can cause considerable irreparable damage to cells and alter the structure of cell membranes.

Unchecked, excessive free radicals can result in oxidative stress within the animal, an imbalance between the production of and the body’s ability to neutralize free radicals via the antioxidant defense systems leading to inflammation. Oxidative stress that becomes out of control can overpower the horse’s immune system to internally defend itself and may result in tissue damage. High oxidation levels may inhibit the immune system. Inflammation and oxidative stress are closely related and often go hand-in-hand. In a terrible cycle, free radicals produce oxidative stress, which leads to inflammation, and inflammation increases the production of free radicals.

The Farmacy: Feeding a Natural Diet

Fortunately, the most natural food for the horse — fresh pasture grass— is considered an anti-inflammatory food. This is due to a fiber content that is excellent not only for motility of the digestive tract but also to nourish the microbiome of the cecum and colon, the massive fermentation vat of the hindgut that houses beneficial bacteria to break down forage and create the B vitamin complex, vitamin C and other nutrients. A well-functioning digestive tract and healthy microbiome is essential to inflammatory balance and immunity. Grass provides vitamin E and beta-carotene — vitamin A’s precursor — as well as essential minerals, including calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, zinc, copper, selenium and others.

Fresh grass also offers an ideal ratio of essential fatty acids. As a grazing herbivore, horses have evolved on a natural foraging diet that contains a fatty acid ratio of up to five times the total amount of omega-3 fatty acids than omega-6 fats. Because of this, they are often considered “omega-3 animals” and thrive on a grass-based diet. Omega-3 and omega- 6 fats are necessary for the well-being of the horse, but the dietary ratio is critical to maintain normal, healthy levels of inflammation. It is in the animal’s best interest to emulate the natural forage- based diet as much as possible.

All the way down to the level of the cell, ingested fatty acids are incorporated into each of the trillions of cell membranes throughout the body. The composition of the cell membrane directly affects the cells’ ability to function. When greater quantities of omega-3 fats are present in the diet, the resulting changes in membrane fluidity and integrity, as well as cell receptor signaling and protein synthesis, can support the biological response to trauma, infection and inflammation. This is the main reason that these specialized fats are able to support so many different areas of the body. For example, these changes can be reflected by healthy skin and hair coat, as well as healthy digestive and reproductive function.

For horses without regular access to grass, provide quality hay consistently to emulate the natural grazing environment and high-fiber requirements necessary to support a healthy digestive tract. Give a comprehensive supplement that provides omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, vitamins and trace minerals to balance a forage-based diet and reduce the need to feed additional concentrates. Decrease sugar in the diet by minimizing or eliminating grains and keep horses in a moderate body condition to help reduce obesity and the risk of inflammatory health complications. Lastly, exercise is important to health and reduces inflammation by making cells more receptive to insulin as well as supporting a healthy body condition. Even small amounts of low-impact exercise can be beneficial and support healthy glucose/insulin regulation. Just like the doctor ordered, diet and exercise can have a profound effect on systemic inflammation.

Have No Fear, Antioxidants are Here

Antioxidants are the horse’s natural defenders that mop up metabolic oxidation. They scavenge free radicals preventing or neutralizing free radical damage, limiting oxidative stress. The complex network of antioxidant metabolites and enzymes work synergistically to prevent oxidative damage to cellular components such as DNA, proteins and lipids.

Endogenous antioxidants are created within the cell itself, and exogenous antioxidants or antioxidant co-factors are consumed in the diet. The body can make five endogenous antioxidants — superoxide dismutase, alpha-lipoic acid, coenzyme Q10, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. The most familiar exogenous antioxidant is vitamin E. This major fat-soluble antioxidant utilizes its lipophilic nature by incorporating itself into cell membranes where it protects unsaturated lipids and other susceptible membrane components against oxidative damage. Vitamin E is uniquely suited to intercept peroxyl radicals and thus prevent a chain reaction of lipid oxidation. Another exogenous antioxidant is beta-carotene, which is converted into vitamin A internally. Vitamin C is typically considered exogenous in most species, although the horse possesses the enzyme necessary to manufacture this vitamin in the liver. Copper, zinc, manganese, iron and selenium are exogenous co-factors sometimes mislabeled as antioxidants but actually have no antioxidant actions themselves. They are, however, essential for the formation of the endogenous enzymatic antioxidants. For example, selenium is necessary for the formation of glutathione peroxidase. The antioxidant metabolites and enzyme systems appear to have synergistic and interdependent effects on one another where the proper functioning of one relies heavily on the availability of another.

Food, Simply

Food is fuel, but it must also be nourishment. The diet affects each horse’s body at the cellular level and can elicit a response to how the animal looks, feels and behaves stemming from within. Science has shown that the most beneficial diet for all horses encompasses quality forage that is supported by specific nutrients to create a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, amino acids, vitamins and minerals. The diet is critical to a normal, healthy inflammatory response and a strong immune system. What the horse eats on a day-to-day basis has the potential to affect this. And choosing a more natural, forage-based diet can help maintain normal levels of inflammation.

The most natural food for the horse — fresh pasture grass — is considered an anti-inflammatory food.

Feeding Tips for Normal, Healthy Inflammation Levels

- Provide pasture and/or hay as the majority of the diet

- Give a daily comprehensive omega-3 supplement with vitamins and minerals to balance a forage-based diet

- Include antioxidants, like vitamin E, particularly for horses without access to fresh pasture

- Choose unmolassed, soaked beet pulp, or hay pellets as low-sugar supplement carriers

- Test hays and pastures for sugar and starch content

- Eliminate sweet feeds

- Avoid corn, soybean and wheat germ oil

- For horses that need calories to maintain weight or hardworking equine athletes, choose digestible, low-non-structural carbohydrate feeds or healthy oils, like flax oil

by Emily Smith, MS,

Platinum Performance®

You May Also Like

Feeding Frenzy: A Forage-First Approach

It's Time to Change Traditional Feeding; Forage as the Foundation, or Entirety, of the Diet is the Healthiest Choice.

Read More about a Forage-First Approach

The ABCs of Horse Vitamins and Their Vital Role in Equine Health

Incredibly relevant to your horse’s health, potency of vitamins decreases with storage time of forage and feeds.

Read More