With Numerous Variables at Play, Renowned Veterinarians Discuss The Study of Trigeminal Mediated Headshaking in Horses, Recent Advancements and Practical Advice for Patient Management

Modern equine veterinary medicine continues to awe in its ability to constantly iterate, better understand and more effectively prevent, treat and even cure the conditions that compromise the health, performance and quality of life of the horses we love. Veterinarians, by nature, are extreme innovators and nimble stewards of medicine who are both never satisfied and forever curious. Perhaps this is why the industry fosters hope in the wake of the deep frustration felt with each case of trigeminal mediated headshaking (HSK), also known as equine idiopathic headshaking. This condition is cruel and can incite severe agitation in afflicted horses. “This affects performance, but most importantly, it affects a horse’s quality of life and, like many other neurologic disorders, often results in euthanasia,” says Dr. Monica Aleman of the hard reality veterinarians face when confronting HSK. Dr. Aleman would know; she’s an internationally-celebrated veterinarian and board-certified specialist by the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine in both large animal internal medicine and neurology and neurosurgery. The recipient of the first-ever University of California Presidential Chair in Equine Neurology, Dr. Aleman has received numerous awards for outstanding work in clinics, research and service and has achieved recognition by the American Veterinary Clinicians for Excellence in Neurology. She is currently co-director of the Neuromuscular Disease Laboratory at UC Davis, where samples from both humans and animals are processed. Clearly, the horse has and will continue to realize great benefit from Dr. Aleman’s passionate dedication to the field of neurology and enigmatic conditions, such as HSK. “Something needed to be done, and I thought that perhaps I could contribute,” she says of her work studying HSK and treating clinical cases. “Last week alone we saw three headshakers at UC Davis, and I consulted on two more cases. This week we have another two cases in our hospital. That means the disorder is out there.”

Dr. Aleman’s unique abilities and keen interest in equine neurologic health have already propelled the understanding of HSK forward monumentally. Pair those strengths with another veterinary powerhouse like Dr. John Madigan, and the possibilities are truly endless. Like Dr. Aleman, Dr. Madigan hails from UC Davis, a further testament to this institution’s reputation as being at the forefront of discovery in numerous areas of equine veterinary medicine. Dr. Madigan too is a board-certified internal medicine specialist and animal welfare expert, aside from his decades-long interest in neurology. He’s authored two textbooks and over 250 scientific publications in peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings and is responsible for several groundbreaking medical discoveries and inventions that have directly improved the lives of animals worldwide. Dr. Madigan has quite literally “been there and seen that” when it comes to HSK and its evolution. “The first cases I saw were a long time ago and were thanks to several clients — who all happen to be observant women — who knew their horses and were able to independently recognize that the way their horses were acting out was a real problem, not a behavioral problem,” remembers Dr. Madigan. “Something was bothering these horses. We couldn’t tell them at the time that what they were seeing was a malfunction of the trigeminal nerve, but they knew something was wrong.” It’s a point that both Drs. Aleman and Madigan drive home insistently — horse owners are the key to the equation in the battle against HSK. No one knows a horse quite like its owner, trainer or rider, and it’s with their help that HSK cases can be identified earlier, diagnosed more accurately and treated appropriately.

“This affects performance, but most importantly, it affects a horse’s quality of life and, like many other neurologic disorders, often results in euthanasia.”

— Monica Aleman, MVZ Cert., PhD, DACVIM (LAIM, Neurology), University of California at Davis

As Drs. Aleman and Madigan began to immerse themselves into the study of HSK, they found that neuropathic pain was likely the culprit behind the extreme headshaking behavior they’ve witnessed. “The horses were showing evidence of electrical sensation — itching, tingling, moving their lips, rubbing their nose and snorting,” notes Dr. Madigan. He continues, “There were a lot of people who doubted that this is what was really happening, but we’re convinced.” Dr. Aleman, who was involved in early electrophysiology studies conducted together with her now-late mentor, Dr. Terry Holliday, agrees with Dr. Madigan. “We saw how this sensory nerve fires and the difference between a normal control horse versus a horse with suspected HSK,” she recalls from this early work. “We found that actually, it can take almost nothing to trigger this severe sensory nerve response in headshakers, but healthy horses won’t react. For normal horses, it will take about 10 to 20 times the amount of a stimulus to trigger the nerve compared to a trigeminal neural horse. That’s how we came up with the name of trigeminal mediated headshaking because it’s completely different to any other type of headshaking.”

By “different,” Dr. Aleman is alluding to the unique manner in which HSK horses shake their heads compared to a horse experiencing a more normal annoyance that may cause it to randomly, briefly and more horizontally thrash its head. HSK is unique in that it involves the trigeminal complex specifically and its trademark is intense nerve pain in the head. Zeroing in on this particular nerve, Drs. Aleman and Madigan have made further advancements in the study and understanding of HSK. “There are different types of headshakes, and they could have different etiologies,” Dr. Aleman observes. A veterinarian will typically rule out other medical reasons for headshaking behavior, such as middle ear disorders, ear mites, cranial nerve disorders, guttural pouch infection or head trauma. “The first step for horse owners sounds simple, but it’s the most important. If you see your horse shaking its head consistently, grab your phone and start filming, so your veterinarian can see it happening. Believe it or not, the way horses shake their heads may be very revealing as to what the underlying cause may be.” Dr. Aleman often describes the difference between more normal headshaking and trigeminal mediated headshaking as picturing a dog or a horse with a tick or other annoyance in their ear. The animal will often flip the ears and shake their head from side to side in an attempt to relieve the annoyance or remove it. This is normal behavior and not indicative of HSK. The same holds true for horses that may stretch their head and neck and exhibit exaggerated chewing behavior. This can indicate temporomandibular joint issues (TMJ) rather than HSK. In contrast, horses with HSK exhibit uncontrolled, violent headshaking that is almost always vertical (though it can sometimes go in various directions due to the rapid jerking motions of the head). Dr. Madigan has seen more than his fair share of HSK horses through his work alongside Dr. Aleman. “I’d say upwards of 90 percent of horse owners say that the behavior they witness is as if a bee went up their horse’s nose,” he analogizes. “Again, the most important piece of the puzzle is observation. The nerve is not damaged. There are no vacuoles (small cavities or space in the tissue). There’s no histology there (microscopic damage of the tissue). It’s a functional problem.” While other diagnostics can come into play, observing and documenting the horse’s headshaking behavior remains a key step in the process.

“Again, the most important piece of the puzzle is observation. The nerve is not damaged. There are no vacuoles (small cavities or space in the tissue). There’s no histology there (microscopic damage of the tissue). It’s a functional problem.”

— John Madigan, DVM, MS, DACVIM, DACAW, University of California at Davis

Importance of an Accurate Diagnosis

While veterinary researchers like Drs. Aleman and Madigan continue to make forward progress in understanding the nuances of HSK, their human counterparts are doing the same. Humans can suffer from a condition known as trigeminal neuralgia, which can have striking similarities to horses afflicted with HSK. Research on both humans and horses has come together and paved a way for vital understanding and a better handle on treatment for both conditions. Perhaps most notably, this translational approach has taught researchers and practitioners the importance of an accurate and expeditious diagnosis. “If you don’t have the right diagnosis, lots of mistakes are going to be made,” says Dr. Aleman. “One of the most common mistakes made with trigeminal neuralgia is that it’s assumed that the patient has a dental problem. In the end, and even after those patients sometimes have teeth removed, they remain in pain because it was never a dental problem. The same thing applies to the horse. If you have the wrong diagnosis, you’re not going to be able to help these horses.” Trigeminal neuralgia is unfortunately an exceedingly painful and debilitating condition, and doctors, like veterinarians, struggle to accurately and efficiently find both a diagnosis and treatment plan that will yield results.

Continuing collaborative efforts between equine and human practitioners and researchers holds substantial promise as the pathway toward eliminating the potentially life-threatening equine condition HSK, as well as its human counterpart, trigeminal neuralgia.

The Etiology of Trigeminal Mediated Headshaking

A common lament over HSK is that we simply don’t know what we don’t know. There is much to be discovered and Drs. Aleman and Madigan are motivated to say the least. The exact etiology of HSK is unknown. However, several suspects have been pin-pointed. A hypersensitivity of the trigeminal nerve to a variety of stimuli, inflammation of the trigeminal ganglia or an immune-mediated reaction may be causative factors of the disorder. The trigeminal nerve is responsible for facial sensation and consists of three branches (the ophthalmic, maxillary and mandibular), running from the back of the head, around the ears, along both sides of the face and terminating in the nose and muzzle area.

Many triggers for headshaking have been reported, though it’s important to emphasize that these stimuli are provocations, not necessarily causes of the disorder. “When we were doing the electrophysiology study, one of the severe cases was experiencing violent headshaking behavior. That horse was able to go into remission, showing us that the nerve can be switched off and on depending on factors like the season,” says Dr. Aleman of what was a major discovery.

Contributing Veterinarians

Monica Aleman,

MVZ Cert., PhD, DACVIM

(LAIM, Neurology)

University of California at Davis

John Madigan,

DVM, MS, DACVIM,

DACAW,

University of California at Davis

Seasonality

Questions remain as to the underlying cause of this change in headshaking behavior noted above, but it showed that horses can, in fact, be seasonally affected, experiencing HSK symptoms most commonly in the spring, summer and sometimes in the fall. Dr. Madigan elaborates, “We think it’s really linked with photoperiod in a lot of horses. We have some horses we follow year after year, and they’ll start within the first week of April and go until the fall, then stop completely.” There are several hypotheses as to why this may be, with allergies being an obvious theory, amongst others. “We see our longest days in June, which is also when allergens are coming up,” points out Dr. Madigan. “Photoperiod has a lot to do with HSK in our experience.”

Is Your Horse a Headshaker?

If your horse displays these signs, talk to your veterinarian:

- Repetitive, involuntary up-and-down headshaking in a vertical motion

- Sudden intense downward flick of nose or entire head and neck in more severe cases

- Scratching or rubbing of the nose and muzzle on objects vigorously and incessantly

- Rubbing on front legs or striking at the nose with forelegs

- Seeks unusual places for shade such as hiding the head in buckets or barrels to block light

- Affected horses may flip the head in reaction to wind, movement and stress

- Extreme nose blowing, snorting and coughing

- Displaying symptoms in spring and summer that abate in winter months

- Headshaking is exacerbated with exercise

A Hormonal Component

Other theories regarding potential triggers of HSK are being explored as well, and one intriguing example proposes gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) as an underlying factor. Gonadotropins are glycoprotein hormones secreted by gonadotroph cells of the pituitary gland following activation from GnRH, which is released from the adrenal gland. Adrenal output of GnRH is naturally guided by seasons and tends to be low when sunlight exposure is curtailed but higher when sunlight exposure increases. “If you talk to an equine reproductive veterinarian, they’ll say that we see a gonadotropin surge when days start getting longer,” explains Dr. Madigan. Another avenue of this theory is that the early spring sees the start of breeding season, when gonadotropin hormones naturally escalate following an increased release of GnRH. One role of gonadotropin hormones is to regulate the activity of the testes and ovaries. “With geldings, you don’t have any testosterone feedback,” highlights Dr. Madigan, potentially providing an explanation as to why the great majority of HSK cases are, in fact, geldings. “We’re looking at gonadotropin levels and how they might be causing gene expression changes that would alter the channels that regulate the trigeminal nerve,” he explains. This focus was inspired by an obscure lecture on adrenal disorders in ferrets that Dr. Madigan once found himself in. “This man gave a brilliant talk showing that castrated or spayed ferrets had hyperadrenal cortices and a receptor on their adrenal glands for gonadotropin. Their levels were very high, and it caused an altered gene expression and hence organ dysfunction,” remembers Dr. Madigan. “We could say the trigeminal ganglion is dysfunctional because gonadotropins are causing these problems,” he concludes as a theory. Another cog in the wheel of the hormones and HSK is related to luteinizing hormone (LH). LH is a gonadotropin released by the pituitary gland in response to GnRH. Dr. Madigan recalls a particular experience supporting this concept of LH involvement. “I was in New Zealand and shown a three-year-old filly racehorse. She obviously doesn’t fit the epidemiology but here she is at Massey University, about to be euthanized and they say, ‘We understand you do some headshaking work,’ ” remembers Dr. Madigan. “I look at her, she’s flipping her head violently, and I asked if they had checked her ovaries. They palpate her ovaries, and they’re tiny. After we sent her LH sample to the South Island, we learned that she had the highest LH level ever recorded in that laboratory. We vaccinated her with a GnRH inhibitor and her headshaking went away in eight weeks. There’s some gonadotropin cofactor there, and definitely something to be learned about seasonality and gonadotropins.”

Dr. Aleman agrees that HSK is a disease with multiple triggers impacting the trigeminal complex, no question. And while, yes, the majority of cases are geldings, there must be a hormonal component at play in some way. “What is triggering that nerve?” she often asks herself. “Of course, as an owner or veterinarian, you’re desperate to help these poor horses. It’s painful to watch. Ourselves and others, we’ve tried multiple treatments and we continue to learn. What works for some doesn’t work for others because of the varying triggers. There’s so much more to know and so much more to discover.”

“... Remember that the trigger isn’t the cause. The cause is the nerve. The trigger is what is turning it on. ...”

— John Madigan, DVM, MS, DACVIM, DACAW, University of California at Davis

Photosensitivity

Aside from a potential tie-in to allergic responses seen seasonally in the spring through fall and the theory of a gonadotropin hormonal component, there have been significant breakthroughs made in the area of photosensitivity (hypersensitivity to light exposure) and the role it plays as a leading trigger for horses afflicted with HSK. Very simply, HSK cases often realize relief when they’re out of the sun. Drs. Aleman and Madigan, through their research, have seen numerous cases triggered by a multitude of stimuli, with photosensitivity being one of the most common exacerbators. “We had a horse that was a very bad case,” remembers Dr. Madigan. “It started for this horse in April when the owner was pregnant and couldn’t ride him for a period of time. A contributing factor that we’ve found is actually weight gain. This particular horse had been in heavy exercise, then was suddenly laid off. This and other cases have shown us a pattern. We don’t see HSK as often in horses that are in heavy work. It’s interesting. With this horse, he was a photic headshaker, and he was bad. The owner was going to put him to sleep. I didn’t have any grant money, so I took him home with me and put him in a stall. When I put him in a dark room to have the ophthalmologist come look at him, he ceased shaking. We then took him outside and I took a jacket from one of the residents and put it over his head to blindfold him. He stopped headshaking. We wrote a paper on our experience with him and had seven more similar cases in there. We call it optic trigeminal summation and it’s similar to the photic sneeze you experience when you see sunlight and can’t control your sneeze. That’s a pathway from the optic nerve to the trigeminal nerve, and if the horse’s trigeminal nerve is not stable, then the light can be a major trigger.”

To further support photic headshaking cases, Dr. Madigan worked with a prominent physicist to make improvements to the traditional photosensitive goggles that are sometimes suggested for these patients. “There are some newer products that are pretty fancy and can be effective. What we did is test yellow, pink and blue filters in the goggles. Although we could not detect a specific wavelength, we saw that the darker the lens the more comfortable the horses were. If your horse doesn’t have the connection between the trigeminal nerve and the optic nerve, then don’t waste your time and money, but I’d say 30 percent of cases have the light component,” he says.

The Impact of Sound

Further proving that multifactorial influences trigger headshaking behavior in HSK cases, environmental factors as seemingly insignificant as sound can spur an attack of the trigeminal nerve. “Again, herein lies the value of observation,” says Dr. Aleman. “Thanks to observant owners we’re able to put these pieces together on behalf of the horse. We’re able to ask, ‘What do you notice when your horse starts headshaking?’ In the case of the first horse that we saw who was being activated by sound, I asked ‘What happened in your barn when the horse started this behavior?’ Initially, the owner couldn’t pinpoint anything, but after some specific questions she offered some great information. She said, ‘Every time my horse starts headshaking, the farrier has been to the barn just before that.’ Of course, it's not the farrier’s fault, but when the farrier comes and starts using hammer on metal, it creates a very sharp sound that was triggering the horse,” explains Dr. Aleman. “I suggest to clients that they keep a diary that documents what happens before and during headshaking events. You may not notice anything initially, but we can often start to see some trends. Dr. Madigan agrees, “For these horses, a simple clap of the hands can be like a punch to the face. You can clap right in front of these horses and at first they’re scared, but they’ll get to the point where they’re striking at you because the sound is going from the eighth nerve to the trigeminal.”

“Regardless of what other treatment modality we use, diet is essential if we want to manage the headshaking better.”

— John Madigan, DVM, MS, DACVIM, DACAW, University of California at Davis

The Dietary Component

Perhaps one of the most universal discoveries Drs. Aleman and Madigan have made in HSK horses is the role that diet plays in both the exacerbation of symptoms and also the easing of headshaking behavior when certain adjustments are made. “We need to start with diet, no doubt,” insists Dr. Aleman. “Regardless of what other treatment modality we use, diet is essential if we want to manage the headshaking better.” Through dietary-related research performed in conjunction with Shara Sheldon, PhD, of UC Davis, both Drs. Aleman and Madigan have learned a great deal. “We’ve had a number of horses donated to us here because their owners were desperate to do something to help them rather than face the alternative of euthanasia. They come to us here in California from all over the country, and prior to their arrival, we’d see them on video and confirm that, yes, they were indeed headshakers. They’d arrive and shortly thereafter they weren’t shaking anymore. Months would go by and no shaking,” says Dr. Aleman of the team’s initial surprise and question. “Now we know, it certainly wasn’t a lack of light, it wasn’t the season necessarily, but what we had done is change the diet.” The horses were on a diet where alfalfa made up over 50 percent of the ration, often with elevated levels of magnesium. “We had essentially changed the alkalinity of these horses’ bodies and it made a marked difference,” says Dr. Madigan of their initial work in dietary intervention. With a fairly simple solution of sodium bicarbonate, Drs. Aleman and Madigan saw an immediate response in their headshaking cases. “We quantified the number of headshakes per minute and saw a reduction,” says Dr. Aleman. “We learned that the more acidic the horse is, the more they shake.” In contrast, as a horse’s system becomes more alkaline, their headshaking has been shown to decrease.

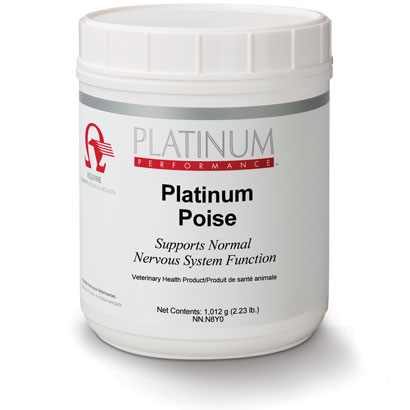

To further their work on diet and its role in headshaking symptomology, Drs. Aleman and Madigan sought to dive deeper into their theory that magnesium can play a pivotal role in supporting HSK cases. “Magnesium lowers the threshold for nerve firing in a lot of circumstances,” states Dr. Madigan. The team began to feed magnesium and saw positive results. It was then that the team’s theory shifted to include a combination of both magnesium and boron together. To determine if boron can augment magnesium’s positive effects among headshakers, Dr. Madigan’s team utilized six horses diagnosed with HSK. All horses received the following three treatments: magnesium + boron, magnesium only and no supplement. Following each treatment period, headshaking severity was scored by three blinded evaluators. Although both magnesium groups responded positively, Dr. Madigan points out that “the best reduction in headshaking occurred with magnesium and boron together rather than magnesium alone.” The challenge then became determining the right combination of both nutrients to be safe and effective, then to establish quality sourcing. “We went to Platinum Performance®, and the research team there helped us with formulation. We’ve been friends with the team there for many years, and they did this with us with no guarantee that it was going to work. We were convinced we were on the right track though,” explains Dr. Madigan. It was out of this theory and subsequent development and testing a formula containing the combination of magnesium citrate and boron citrate — came about. Two of the primary factors that Drs. Aleman and Madigan were concerned with were bioavailability (absorbability) and purity. “There are so many products out there that have magnesium, but that doesn’t mean it will get absorbed. A lot of them are combined with so many other things that can affect absorption,” cautions Dr. Aleman. The work performed with both magnesium and boron by Drs. Aleman and Madigan and their team can be found open-access in the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Supports Normal Nervous System Function

Platinum Poise

To support normal nervous system function and healthy neural activity.

For best results, Platinum Poise should be used in conjunction with our foundation formula: Platinum Performance® Equine.

Show Safe

Active Ingredients Per (33,73 g) Serving

Boron Citrate 21 g

Magnesium Citrate 12.6 g

Paving the Way for Future Impact

Although tremendous progress has been made in the field of study relating to trigeminal mediated headshaking, there still remains much to learn and explore. Drs. Aleman and Madigan, through extreme dedication and tireless research, have improved the quality of life and future prospects of those horses suffering with HSK. Though the condition remains largely mysterious, their discoveries have moved the needle and opened doors leading to future revelations — puzzle pieces that will inevitably come together thanks to their work. “The goal is to make the horse comfortable and ideally allow them to be ridden again,” says Dr. Madigan. He and Dr. Aleman remain convinced that a more structured diagnostic methodology opens the door to more effective and reliable treatments. Together they urge veterinarians to really listen to their clients and encourage vigilant observation. “As veterinarians we don’t want a quick 15-minute look at the horse; it requires time and some study,” says Dr. Madigan from experience. “Start some interventions, look for triggers and remember that the trigger isn’t the cause. The cause is the nerve. The trigger is what is turning it on. If you can modify the trigger, then great, but keep in mind that things can fluctuate with these horses,” he cautions.

As Dr. Aleman, Dr. Madigan and their research team continue to forge ahead, the outlook for HSK prevention and treatment will continue to improve. This work can be frustrating but there is still much to learn on behalf of horses suffering from this severe and debilitating condition. In addition, the vital research from UC Davis (and elsewhere) has the potential to translate over to humans suffering from the HSK-similar condition, trigeminal neuralgia. Drs. Aleman and Madigan are the epitome of dedication, and if progress is out there to be made, they certainly will chase it unrelentingly. “There’s a lot of work to do,” insists Dr. Aleman. “We’re not done.”

Research Cited

1. Pickles KJ, Madigan JE, Aleman MR. Idiopathic headshaking: is it still idiopathic? Vet J. 2014;201(1):21–30.

2. Aleman, MR. Trigeminal-Mediated Headshaking. In Reed SM, Warwick BM, Sellon DC:Equine Internal Medicine, 4th ed. St. Louis, Elsevier 2018, pp, 680-682.

3. Madigan JE, Bell SA. Owner survey of headshaking in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219:334-337.

4. Carr, EA, Maher, O. Neurologic causes of gait abnormalities in the athletic horse. In Hinchcliff KW, Kaneps AJ, Geor RJ:Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery, 2nd ed. St. Louis, Elsevier 2014, p, 514.

5. Madigan JE, Kortz, G, Murphy C, et al. Photic headshaking in the horse: 7 cases. Equine Vet J. 1995;27:306-311.

6. Lane JG, Mair TS. Observations on headshaking in the horse. Equine Vet J. 1987;19:331-336.

7. Hunt CD, Herbel JL, Nielsen FH. Metabolic responses of postmenopausal women to supplemental dietary boron and aluminum during usual and low magnesium intake: boron, calcium, and magnesium absorption and retention and blood mineral concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:803-813.

8. Sheldon SA, Aleman M, Costa L, Weich K, Howey Q, Madigan JE. Effects of magnesium with or without boron on headshaking behavior in horses with trigeminal-mediated headshaking. J Vet Intern Med 2019:1-9. Doi:10.1111/jvim.15499.

9. Sheldon SA, Aleman M, Costa L, Santoyo AC, Weich K, Howey Q, Madigan JE. Luteinizing hormone concentrations in healthy horses and horses with trigeminal-mediated headshaking over an 8-hour period. J Vet Intern Med 2019:1-4. Doi.org/10.1111/ jvim.15452.

10. Sheldon SA, Aleman M, Costa L, Santoyo A, Howey Q, Madigan JE. Infusion of intravenous magnesium sulfate and its effect on horses with trigeminal-mediated headshaking. J Vet Intern Med 2019:1-10. Doi:10.1111/jvim.15410.

11. Sheldon SA Aleman M, Costa L, Santoyo C, Howey Q, Madigan JE. Alterations in metabolic status and headshaking behavior following intravenous administration of hypertonic solutions in horses with trigeminal-mediated headshaking. Animals 2018;8(102). Doi:10.3390.

12. Pickles K, Madigan JE, Aleman M. Idiopathic headshaking: Is it still idiopathic? The Vet J. 2014;201:21-30. 13. Aleman M, Rhodes D, Williams DC, Guedes A, Madigan JE. Sensory evoked potentials of the trigeminal nerve for the diagnosis of idiopathic headshaking in a horse. J Vet Intern Med 2014;28:250-253.

14. Aleman M, Williams DC, Brosnan RJ, Nieto JE, Pickles KJ, Berger J, LeCouteur RA, Holliday TA, Madigan JE. Sensory nerve conduction and somatosensory evoked potentials of the trigeminal nerve in horses with idiopathic headshaking. J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:1571-1580.

15. Aleman M, Pickles KJ, Simonek G, Madigan JE. Latent equine herpesvirus-1 in trigeminal ganglia and equine idiopathic headshaking. J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:192-194.

You May Also Like

Neurologic Health

Formulas to support healthy equine neurologic function

Read Moreabout Equine Neurologic Health