Boarded Internal Medicine Specialist Dr. Amy Polkes Answers Questions on Ulcers, Their Causes, Treatment and Prevention

When it comes to equine ulcers, few veterinarians encounter them more frequently than Amy Polkes, DVM, DACVIM. She brings deep knowledge on the subject as a board-certified equine internal medicine specialist serving primarily Maryland and Virginia but also New York and Connecticut through her ambulatory referral practice, Equine Internal Medicine and Diagnostic Services (Equine IMED). This region of the country is brimming with sport horses, and with an overwhelming number of equine athletes experiencing some form of ulcers in their lifespan — 60-90%, according to the American Association of Equine Practitioners — Dr. Polkes has developed a vast understanding of the subject courtesy of years of study and daily hands-on experience.

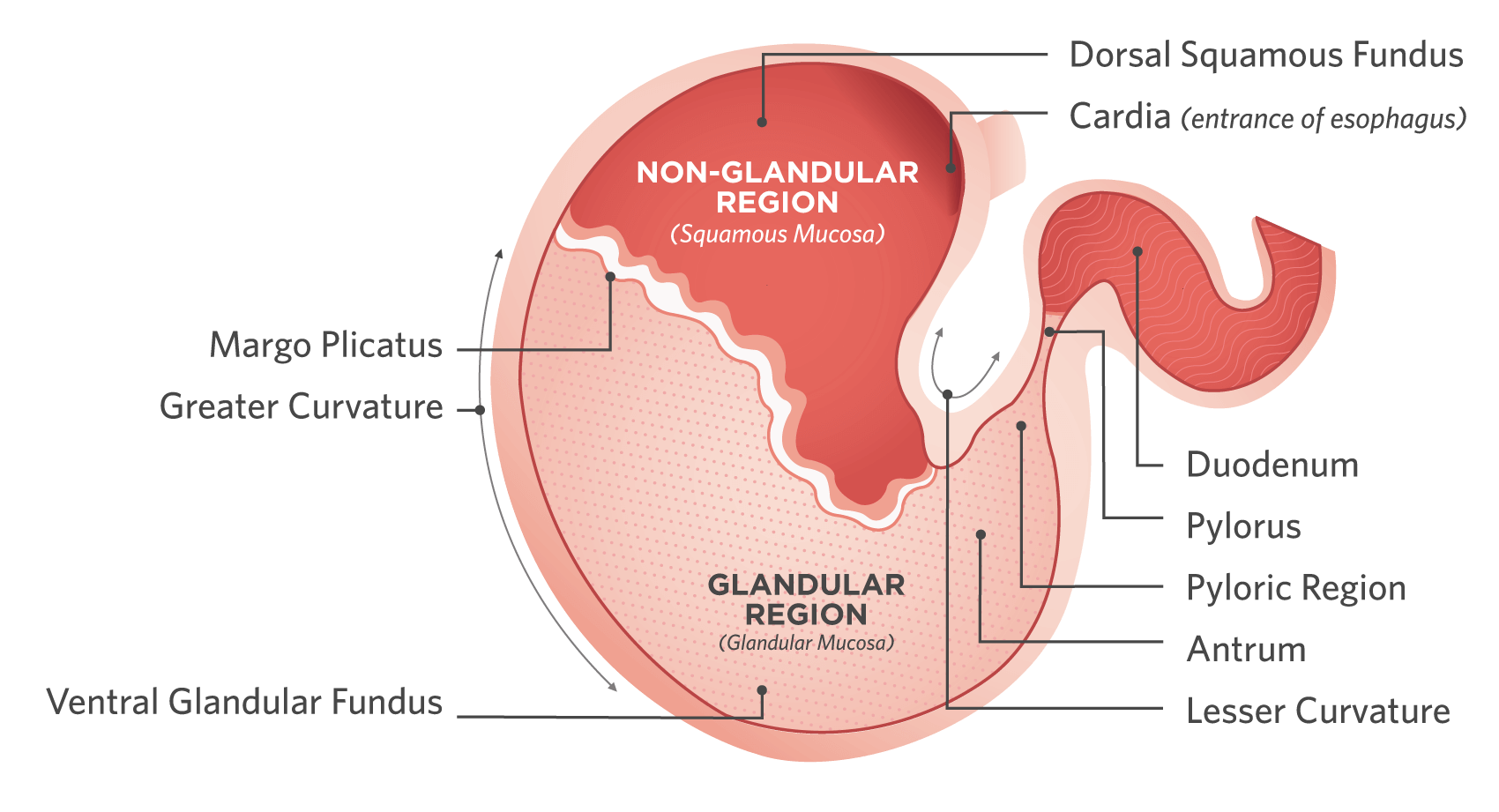

The Equine Stomach

A vital part of the gastrointestinal tract, the equine stomach has various regions that can be impacted by Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome.

Jessie: Dr. Polkes, let’s start with a little bit of anatomy, so we can properly understand the affected regions of the horse’s gastrointestinal, or GI, tract.

Dr. Polkes: Absolutely. We have been talking about ulcers in the horse for over 25 years, but we still do not fully understand all the causes, especially disease in the glandular portion of the stomach. This illustrates the complexity of this disease and how we are still learning. It was only when we had the equipment to scope the horse (gastroscopy) that we better understood how the unique anatomy plays a significant role in how we approach ulcer disease. At a basic level, we have squamous ulcers versus glandular ulcers, and this distinction indicates the different portions of the stomach. The (non-glandular) squamous mucosa is the top portion of the stomach, almost a continuation of the esophagus. Then, there is a division that spans across the middle of the stomach called the “margo plicatus.” Below this division is the glandular mucosa, where gastric acid is produced, and continues to the pylorus. ... Horses do not have a gall bladder, so they continuously produce bile acid, which exits from the bile ducts in the duodenum, and can reflux back into the stomach.

When we perform gastroscopy we are not only trying to determine if the horse has ulcers but where these ulcers are located. It becomes important to confirm which region of the stomach is affected because these two regions behave differently when it comes to treatment. The most common location for ulcers is in the squamous mucosa above the margo plicatus and/or at the lesser curvature of the stomach. Glandular ulceration generally occurs at the pylorus with varying presentation. The location can often indicate causation and help lead us toward an appropriate treatment plan.

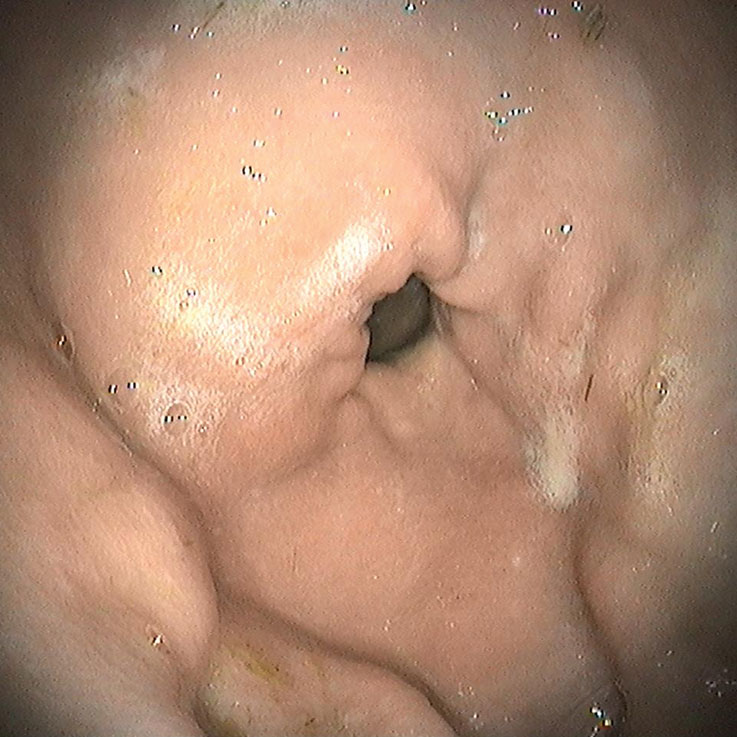

Normal Pylorus

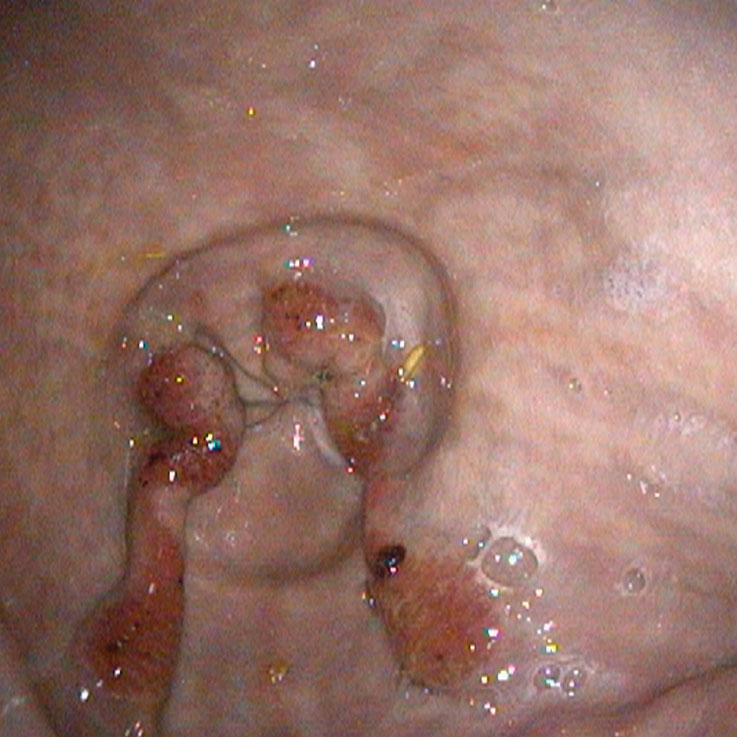

Mild Disease at Pylorus

Moderate Disease at Pylorus

Jessie: Now that we have a firm footing in terms of anatomy, can you describe the prevalence of ulcers?

Dr. Polkes: Prevalence is an important thing to talk about because it has changed with our understanding of gastric ulcer disease and how we can now better prevent disease. There has been a change in feed and management practices with a movement away from high carbohydrate diets and toward feeding horses to accommodate their constant secretion of gastric acid. These changes have lowered the prevalence of disease and improved how we manage horses. Prevalence can also differ depending on the purpose of the horse: are they a performance athlete or retired? Though ulcers can and do occur in any horse — including pasture horses that seemingly live an idyllic, low stress life — they are certainly more prevalent in high performance horses. In the performance horse and racehorse population prevalence can be quite high if they are not managed properly during competition.

Jessie: Let’s talk causes. While some ulcer cases don’t have an obvious cause, are there things that we’re doing as horse owners that can be contributing?

Dr. Polkes: We talked about the high prevalence of ulcers in performance horses, and this is not surprising. These competitive athletes often have a challenging schedule and are more likely to encounter stress with changes in environment during travel. They also tend to be stalled more frequently with limited turn out time. Their socialization with other horses in the barn can be disrupted as well, and all of these things add up to challenges we need to work around.

One of those key management practices is how we feed our horses, which can certainly contribute to their risk for ulcers. Horses constanty produce gastric acid, but saliva associated with chewing acts as a buffer to the gastric acid. When they eat fiber such as grass and hay, this forms a fibrous mat of feed that sits in the stomach. The very bottom of the stomach has the most acidic pH (1-3), and it becomes more basic as it forms layers of feed in the stomach. When we feed horses large infrequent meals rather than more continuous eating as they are intended, acidic fluid accumulates in the bottom of the stomach with no protective feed mat. This acid can then damage the squamous mucosa.

Dr. Alfred “Al” Merritt one of my mentors and professor emeritus in the Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences at University of Florida, did a treadmill study to demonstrate the damaging effect of gastric acid splashing onto the squamous mucosa during exercise. This is known to be one of the main causes of gastric ulcers in performance horses when they are exercised on an empty stomach. It is important to protect the stomach from acidic gastric contents during work by making sure there is a protective layer of feed to buffer the gastric acid. To address these concerns, I recommend managing horses with the simple rule of “fiber and friends.” Horses are social by nature and they spend hours grazing, often traveling long distances in a single day. Feeding horses to mimic their natural grazing behavior is key to gastric health. Providing adequate time outside for horses to graze is crucial, as they need to move/walk to properly digest their food. When they are in a stall, consider feeding hay in a slow feeder or hay net to mimic natural grazing behavior. Slow feeders force the horse to take smaller bites, which in turn creates saliva as they chew. This saliva acts as a buffer in the stomach.

Grain meals should be guided by the level of work the horse is doing and their required caloric intake. Try to avoid feeds that require a large feeding rate as this can be difficult to digest and high-quality fiber (hay) should be the mainstay of nutrition rather than grain. Ration balancers can also be considered for horses in light work or retired horses that have minimal extra caloric needs.

Clinical Signs of an Ulcer

- Anything from a horse that is acutely colicky and significantly painful, to a horse that may only show a behavioral change.

- Horses can sometimes present as “girthy” during saddling or may pin their ears.

- Their eating habits may change.

- Changes in appearance may occur, including poor hair coat, weight loss or failure to gain weight.

Jessie: As a veterinarian, what are some of the clinical signs that lead you to suspect ulcers may be at play in a particular case?

Dr. Polkes: The clinical signs are so varied — anything from a horse that is acutely colicky and significantly painful, to a horse that may only show a behavioral change. Horses can sometimes present as “girthy” during saddling or may pin their ears or try to bite. They can also have changes in their eating habits; they may not eat their hay or grain normally, often taking a bite of feed, then walking away. We also look for changes in appearance, including poor hair coat, weight loss or failure to gain weight.

We need to understand that ulcers can present in many ways with many different causes: high performance demands; travel; stress; changes in management; new hay or feed; or problems with gastric emptying; among a lot of other things. The cause is not that simple, so the clinical signs can vary. I always tell riders/ owners to trust their instincts. They know their horses better than anyone. If you notice something that feels or looks off, get your veterinarian involved and intervene early.

“The horse needs to be fasted for a proper amount of time for the stomach to be empty enough to examine. ... The procedure is performed on the standing, sedated horse.”

— Dr. Amy Polkes, Equine Internal Medicine and Diagnostic Services, discussing the necessary fasting leading up to gastroscopy

Gastric disease is graded according to a standard scale. Squamous disease is graded from one to four with grade one ulcers being superficial with minimal disruption and grade four ulcers being deep into the mucosa.

Jessie: You mentioned diagnostics. The ability to scope horses and get a clear picture of what’s happening in the stomach has been pivotal in terms of accurately identifying and grading ulcers. Talk to me about scoping. What is your process, what are you seeing, and what have you learned after performing so many scopes throughout the years?

Dr. Polkes: I’m going to start with preparation. The horse needs to be fasted for a proper amount of time for the stomach to be empty enough to examine. I recommend a 16 hour fast to get a clear look at the entire stomach, including the pylorus. The procedure is performed on the standing, sedated horse. We want to minimize stress as much as possible, so we try to schedule these appointments for the morning to avoid a long fasting period during the day.

The endoscope is passed through the nose into the upper airway, then the esophagus just as you would to “tube” a horse for colic. Once in the stomach, we may need to insufflate with air to be able to look around the stomach, but we suction this air off at the end of the procedure. I am looking at the overall health of the squamous mucosa and glandular mucosa, for the presence or absence of ulcers and if the stomach has properly emptied for the period of time the horse was fasted. Any feed remaining in the stomach after a confirmed proper fast could indicate a delay in gastric emptying. I also sample the gastric fluid contents to measure the pH of the gastric fluid (normal is a low pH).

Gastric disease is graded according to a standard scale. Squamous disease and glandular disease are described differently. Squamous disease is graded from one to four with grade one ulcers being superficial with minimal disruption and grade four ulcers being deep into the mucosa. The location and number of ulcers is also important. Are there a few large ulcers or many smaller ulcers? Are they in the lesser curvature or greater curvature or both? The location and severity of ulcers can help us both with cause and a treatment plan.

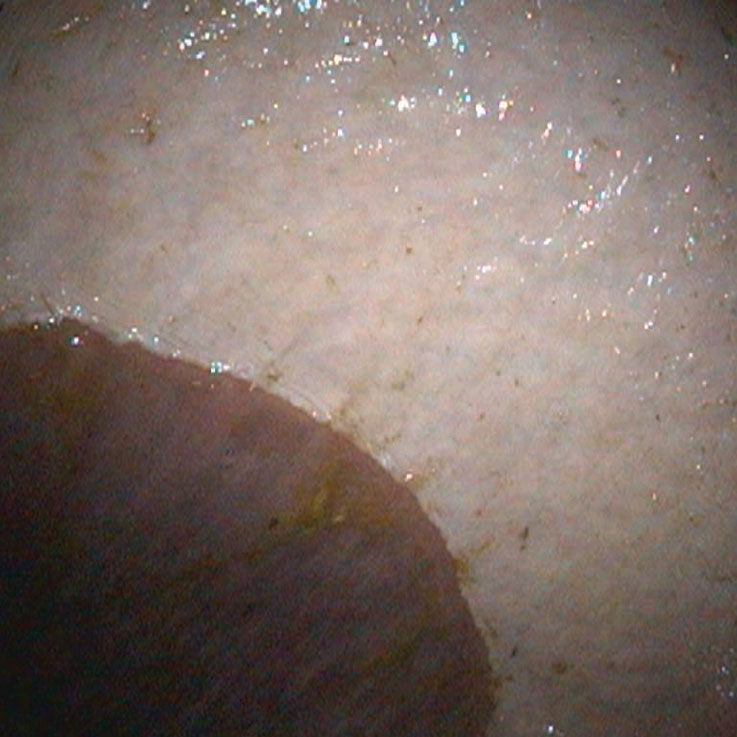

Another thing we may see is hyperkeratosis. Some will refer to hyperkeratosis as a grade zero or grade one ulcer. It’s a yellowing of the mucosa from bile staining, and it indicates that the mucosa has been damaged in that area. Bile comes from the bile ducts into the first part of the small intestine (duodenum) and back into the stomach where you can see the yellow staining. Sometimes, this staining can indicate that the stomach is staying empty too long, which leads us to investigate the cause. Is the horse getting enough to eat? Is there a reason that they are not eating? How are they being fed? There can be other causes for hyperkeratosis, and while it is not a true “ulceration,” it can be an indication of a problem.

Working my way down to the glandular portion of the stomach, we look at the antrum (bottom part of the stomach) and the pylorus (exit of the stomach). We use more descriptive terms to describe these ulcers rather than grading them. Some descriptive terms for glandular disease may be hemorrhagic, fibrinous, swollen mucosa, bleeding or striated. It is important to describe the disease and document it with pictures to follow the progression of healing over time.

To summarize, the cause and treatment of gastric disease can differ depending on the type and location of the ulcer, glandular versus squamous or the lesser curvature versus the greater curvature, as an example.

Normal Lesser Curvature

Mild - Moderate Grade 2 Ulceration at the Lesser Curvature

Moderate Grade 3-4 Ulceration & Hyperkeratosis at the Lesser Curvature

Severe Grade 4 Ulceration at the Lesser Curvature

Jessie: Let’s really zero in on acid and how it’s contributing to ulcers. There has been a considerable paradigm shift in human medicine when it comes to conditions like acid reflux and other gastrointestinal issues. In people, we’re discovering the role of hydrochloric acid and lactic acid in these issues. We thought all along that it was too much acid contributing to these conditions when we’re now finding it may be too little acid. Medicine and science are advancing in that area, and that has caused standard treatments like proton pump inhibitors and antacids to be called into question in a lot of cases. How about the horse? How does acid come into play as a culprit, and how do you handle that?

Dr. Polkes: It’s a great question. We think about acid in the horse, and our minds often go straight to the most-common treatment, omeprazole, which is a PPI, or proton pump inhibitor, drug commercially known as GastroGard®. Its job is to raise pH in the stomach. (In this logarithmic scale, seven is neutral; lower values are more acidic, while higher values are more alkaline.) Normal gastric fluid has a pH of around 1-2 in the very bottom of the stomach. When we treat a horse with omeprazole, we raise the pH to 7 or 8 (alkaline), to allow those ulcers to heal. However, it is important to remember, that gastric acid plays a natural role in health and disease. The stomach is acidic to digest food properly, and if we change the environment in the stomach, we may impact digestion. Changes in pH can disrupt the normal microbial population and this may be transient or more persistent if the pH does not return to normal. I measure the pH of the gastric fluid in horses treated with a PPI to determine if the PPI is effectively raising the pH. In other cases that are NOT receiving a PPI an elevated pH could indicate there is a disruption in the natural gastric flora causing an abnormal elevation.

Jessie: That really underscores the importance of getting a proper diagnosis if ulcers are suspected. You have to know precisely what’s happening before you can properly treat it. You mentioned PPI drugs, but can you give us a deeper look at the different classes of drugs that are available to a veterinarian to consider in ulcer cases? Along with omeprazole, you also have mucosal protectants like sucralfate, and prostaglandin analogs like misoprostol.

Dr. Polkes: Myself and other Equine Internal Medicine Specialists have frequent discussions about treatment and what we think may be the most effective approach as we learn more about gastric ulcer disease. PPIs like omeprazole are a mainstay for squamous ulcers but the glandular ulcers may have a different cause and need a different treatment approach. Glandular disease is not thought to be caused by acidic damage like the squamous mucosa. So, treatment for glandular disease is aimed at mucosal protection and healing. Sucralfate and misoprostol are more typical drugs used for glandular disease.

When there is disease in both the squamous and glandular mucosa it can become tricky, because while altering the pH may positively impact the squamous region, it may simultaneously have negative implications for the glandular region. Also, some of these drugs can interact with each other. A veterinarian should always be consulted prior to starting treatment as these drugs need to be administered properly for safety and effectiveness. For example, omeprazole (GastroGard®) must be given on an empty stomach for it to be effective and you need to wait at least 30-60 minutes after administering to feed. Sucralfate is a mucosal protectant that we use to help heal the damaged mucosa. It likes to stick to everything, so if you give a horse omeprazole and Sucralfate at the same time, you may not be getting the full benefits of either drug. Misoprostol is a bit different. It works to bring good blood supply to the mucosa to aid in healing. So If you are going to treat with all three of these drugs, things can get tricky and labor intensive. I personally do not often use all three of these drugs together. I try to be conservative with treatment and understand that sometimes the drugs we use can have unintended consequences, such as flora disruption or cramping and diarrhea (misoprostol), so I try to treat judiciously and concentrate on management changes that can have more long-term beneficial effects.

Ultimately gastric ulcer disease tends to be secondary to a primary cause. If we can address that primary cause, we will have a better outcome with more longterm success.

Jessie: You’re a major advocate for more judicious use of drugs to treat ulcers. Give us some insight there. What are some of the drawbacks and side effects that horse owners need to be aware of?

Dr. Polkes: I try to be conservative with treatment and understand that sometimes the drugs we use can have unintended consequences. Concentrating on management and nutritional changes can have more long-term beneficial effects. Again, gastric ulcer disease tends to be secondary to a primary cause. If we can address that primary cause, we will have a better long-term outcome. Constantly raising the pH with drugs and supplements can cause changes in the normal gastrointestinal environment. Horses have an acidic stomach for a reason!

The top of the stomach has a frequent cell turnover, and most cases of squamous ulcer disease can be treated successfully with a PPI to complete healing. But the glandular mucosa like the pylorus is completely different. This mucosa does not have rapid cell turnover and sometimes we can not heal this area completely. This does not mean the horse will remain clinically affected. Horses can often be asymptomatic with pyloric disease (chronic). Expectations of achieving complete healing has led to some horses being treated for many months and sometimes years unnecessarily. We need to understand the threshold of healing and what we are trying to achieve with treatment. Sometimes complete healing is not possible, but the horse may be asymptomatic and wax and wane with clinical disease only as they face stressful events, such as shipping or showing. We can aim to treat during these times rather than persistent treatment that may have detrimental effects on the gastrointestinal system.

Dr. Rachel Liepman performs gastroscopy on a patient.

“When we perform gastroscopy we are not only trying to determine if the horse has ulcers but where these ulcers are located. It becomes important to confirm which region of the stomach is affected because these two regions behave differently when it comes to treatment,” says Dr. Amy Polkes. ”The most common location for ulcers is in the squamous mucosa above the margo plicatus and/or at the lesser curvature of the stomach.”

Jessie: Those unintended consequences are important to understand, no doubt. As a horse owner I’m hearing that involving your veterinarian is crucial, getting that proper diagnosis is imperative and identifying the root cause is the best place to start. That leads me to think of prophylactic use of these drugs. As riders we see it often — someone wants to prevent ulcers, so they put their horse on omeprazole, for instance, when they’re hauling or showing. What are your thoughts?

Dr. Polkes: I will see people put horses on omeprazole every time they treat with an NSAID, such as phenylbutazone (Bute). There have been several studies showing this can actually have a detrimental effect due to changes in the microbiome with this treatment. There was an interesting study done by Dr. Canaan Whitfield-Cargile while he was at Texas A&M on the prevention of gastric ulcers in the face of NSAIDs. He looked at the effect of Bute alone, then in combination with a nutritional supplement that contained omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, prebiotics and probiotics. His findings were surprising as the data showed the significant beneficial effect of this nutritional supplement on the gastric microbiome that had a protective effect on preventing ulcers and GI injury. This study really highlights the importance of the microbiome in gastrointestinal health and when we change the environment in the stomach, we can disrupt this balance.

Treatment for gastric ulcers is important, but drugs that can change the normal gastric microbial environment should be used judiciously. Once again, the diagnosis of gastric ulcer disease with gastroscopy is important to outline an appropriate treatment plan for an individual horse.

“I think it is important for veterinarians to help educate clients on the importance of prevention of gastric ulcer disease,” says Dr. Amy Polkes. “Management practices are key to prevention, and there are simple things that can be done for prevention.”

Jessie: Digging deeper into prevention and some strategies to deploy there, it’s important to note that a lot of riders don’t necessarily realize that veterinarians much prefer to be doctors of health rather than doctors of medicine. Taking that root cause, whole-horse approach through proper diet, supplementation and management can go a long way in hopefully avoiding the issues we’ve been talking about. What are your top preventive strategies?

Dr. Polkes: I think it is important for veterinarians to help educate clients on the importance of prevention of gastric ulcer disease. Management practices are key to prevention, and there are simple things that can be done for prevention.

Keep it simple: I find myself doing a fair amount of nutritional consultation in my practice. There is an abundance of supplements advertised for gastrointestinal health. Many of these have no research behind the products, and we don’t know how they work in the horse. Some may be innocuous, but others can be detrimental. My approach is to keep things simple and to consider the natural diet of horses with a “fiber first” approach. Remember horses are continuous grazers because they have no gall bladder. Hay and grazing is incredibly important, but not all hay is considered equal. There are many companies that will test hay for nutritional content, but the physical quality of the hay is also important. Course, stemmy hay can be difficult for some horses with gastrointestinal disease to digest and in some cases may even cause physical damage to the lining of the stomach. Alfalfa is an excellent choice for horses with gastric ulcer disease due to the buffering capacity, but again the quality of the alfalfa is important as the leafy green parts are what you want.

Socialize your horse: Horses are herd animals, and they need to see and touch each other as they would in the wild. Isolation can cause stress, sleep deprivation and other behavioral issues. Consider the stalls in the barn and if horses can see each other over the stall walls and across the isle. Don’t underestimate the need for socialization.

Get your horse outside: Get them outside, grazing and moving. If we ate a big meal and just sat down all day, we would not digest food properly as we would if we were moving. The same goes for the horse. They need fresh air and exercise beyond their time in work, like moving around a pasture. Even if they can’t be on a pasture, create a dry lot and offer hay in that area.

Make informed choices: Many people do not properly research products they are giving their horses. It is important to look at the ingredients and if there is research on using that exact product in horses. Read labels, ask your veterinarian and ask any questions to the company whose product you are considering. Quality and research really do matter for both efficacy and safety.

Supplement appropriately: I have seen an explosion of supplements. An easy step to narrow things down is to choose formulas that have appropriate research and have been studied in the horse. You would be surprised how many products reference research studies on ingredients that were tested in other products but not the one they are selling. I choose Platinum Performance® for this reason. I have complete confidence in the company, the science and the formulas. I also like that they are designed to be safely and effectively fed together.

Use NSAIDs judiciously: NSAIDs inhibit the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes that stimulate prostaglandin, which causes inflammation. However, some prostaglandins are good and help produce the mucus that protects the stomach lining. COX-2 selective NSAIDs and nonselective NSAIDs have been associated with gastric inflammation and ulceration. While they are effective at controlling pain and inflammation, they can inhibit the positive effects of the COX-1 pathways, such as promoting the normal mucosal protectant in the stomach.

We can treat gastric ulcers when they occur, but our goal as veterinarians is to determine the underlying cause so we can help to prevent them from occurring.

Jessie: Diet, supplementation, management, quality sleep, controlling stress levels — singly or in combination — make a significant difference in the horse’s overall health, especially their gastrointestinal health. Truthfully, this isn’t too different from how we should be managing our human selves, not just our horses. As riders, there’s so much we can do to manage our horses more holistically at home and while traveling and showing, using strategies outlined by Dr. Polkes. Additionally, involving our veterinarian in obtaining a proper assessment and diagnosis should be our first step if ulcers or GI dysregulation is suspected. Together, we can determine the best course of treatment, most judicious use of the proper medication(s) for the case and a root-cause approach to help ensure that our horse’s GI health is set up for success in the future.