While it remains a challenge, the prognoses have improved and severely acute cases are more of a rarity with veterinarians having a solid and proven approach to both diagnoses and treatment

The unknown. It’s human nature to fear what we can’t predict. Take that human instinct and add horses to the mix and you have undoubtedly experienced some stress in your life. These animals are the keepers of our joy, the givers of our freedom and the 1,000-pound creatures entrusted to our care who, frustratingly, can’t tell us what’s ailing them. When those ailments include neurologic symptoms, our fear and unease heighten exponentially. Enter Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis (EPM), one of the more unpredictable conditions encountered by both riders and veterinarians. A disease of the central nervous system and brain, EPM often displays neurologic symptoms and can be difficult to pinpoint in terms of what comes next. Luckily, like so many things in veterinary medicine, there has been progress made in the understanding, diagnosis and treatment of EPM. Thanks to the brilliant minds who not only care for the horse but research the origins of disease, a clearer and more definitive picture has formed of the pathophysiology of EPM, what to expect and how to move forward.

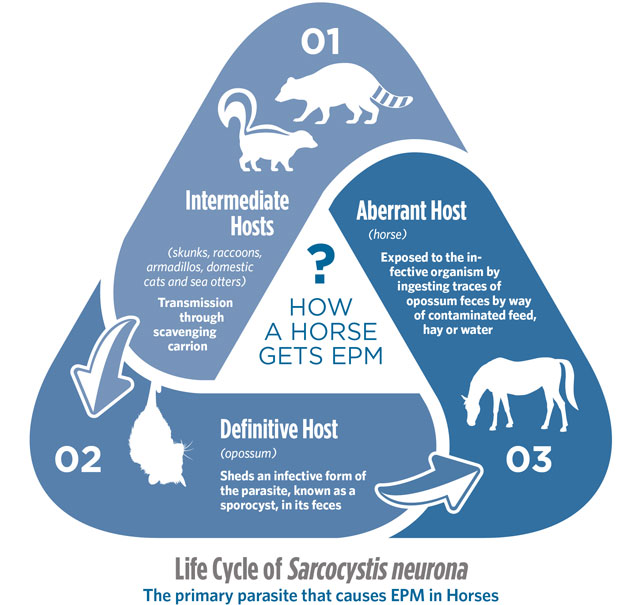

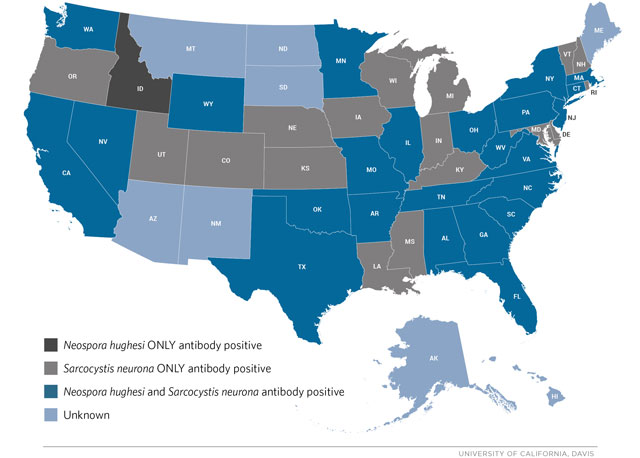

Broken down, EPM has two bad actors at play, per se. The condition is caused by the protozoa Sarcocystis neurona (S. neurona) and, in some cases, the less frequent culprit of Neospora hughesi (N. hughesi). Zeroing in on S. neurona, this parasitic organism requires both a definitive host, known to be the opossum, and an intermediate host, identified as skunks, raccoons, armadillos, cats and, unexpectedly, sea otters. As the definitive host, the opossum acquires the parasite from an intermediate host, then sheds an infective form of the parasite, known as a sporocyst, in its feces. Horses are exposed to the infective organism by ingesting traces of opossum feces by way of contaminated feed, hay or water. Once ingested, the parasite eventually becomes what’s known as a merozoite. In a small percentage of cases, merozoites can make their way to the central nervous system and thus cause EPM. While the thought of EPM-induced neurologic symptoms may sound frightening, there’s a silver lining. An incredibly high percentage of horses have been exposed to S. neurona and are considered seropositive with antibodies against the organism. In fact, the number can be as high as between 53 percent and 90 percent depending on geographic location, with warm, humid locations as well as the state of California being hotspots. On the other hand, according to the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP), only roughly 20 percent of horses in certain areas of the country will test positive for antibodies to the less common N. hughesi. Now for the silver lining — while exposure rates are alarmingly high, only between 0.14 to 1 percent of horses will ever develop clinical symptoms of EPM. The ability to definitively test for these antibodies has given veterinarians an important diagnostic tool, but one that comes with a caveat. The blood test is helpful, yes, but it does not, in fact, indicate whether or not a horse has EPM or will ever exhibit neurological symptoms. It simply indicates they’ve been exposed to the organism.

Though cases of EPM are low in comparison to the high number of exposures, those horses who do become symptomatic have experienced the parasite’s migration. “When that parasite gets into the horse, it disseminates through the body,” explains Dr. Bryan Waldridge of Mississippi State University, a boarded internal medicine specialist with extensive experience in both academia and clinical practice. A born and bred southerner, Dr. Waldridge has seen his fair share of EPM cases. “It appears that once the parasite gets into the neurologic system, it’s sort of isolated from the rest of the immune system and able to find a place to go and complete its life cycle within the horse.” Migrating to the spinal cord, brainstem and brain, the parasite damages neurons and causes inflammation. “Wherever those neurons are damaged, depending on what body function they’re responsible for, that’s where we’ll see clinical signs,” continues Dr. Waldridge.

With clinical signs being determined by the parasite’s location, symptoms can range from asymmetry to ataxia and atrophy. According to the AAEP, asymmetry is characterized by a symptom that is more severe on one side of the body. Ataxia, in contrast, describes horses that are unable to move their body and legs normally. These horses move in an uncoordinated fashion, ranging from subtle to extreme. Atrophy, though a less frequent symptom of EPM, signifies that affected nerves have caused muscle wasting. Asymmetrical ataxia, while a more common clinical sign of EPM, will also be present in numerous other neurologic conditions. “We see horses, for instance, that will just present with spinal ataxia. That’s difficult to distinguish from, say, a compressive myelopathy, or wobblers,” explains Dr. Rodney Belgrave, President of the widely respected Mid-Atlantic Equine Medical Center and a boarded internal medicine specialist. “Those cases are a little tougher. We can see horses that have brainstem involvement, cranial nerve signs and even horses that are dysphagic or have difficulty swallowing. It’s a very unpredictable disease, and for that reason, we consider EPM as a possibility in any horse that presents to us with neurologic signs,” adds Dr. Belgrave. While EPM is most certainly still a present factor in clinical practice, it seems that the instance of acute disease has diminished somewhat over time. “Fifteen to 20 years ago, we were seeing a lot of acute cases of EPM, where the horse would present really acutely neurologic with muscle atrophy to suggest that there was some peripheral nerve involvement. Sometimes they were even recumbent,” remembers Dr. Belgrave. “I’d say those cases are in the minority now. The majority of cases are now presenting with spinal ataxia, which again, can be difficult to initially distinguish from other neurologic conditions.”

“Fifteen to 20 years ago, we were seeing a lot of acute cases of EPM, where the horse would present really acutely neurologic with muscle atrophy to suggest that there was some peripheral nerve involvement. Sometimes they were even recumbent. I’d say those cases are in the minority now.”

— Rodney Belgrave, DVM, MS, DACVIM, Mid-Atlantic Equine Medical Center

The majority of horses will test seropositive for antibodies against S. neurona or the lesser culprit of N. hughesi, but a deeper dive past standard titers is still important to pin down a confirmed diagnosis. “To definitively diagnose it comes down to a spinal tap. We test the spinal fluid to look for ratios of antibodies in the spinal fluid to the serum. That approach has been shown to be more reliable than individual titers in either the serum or cerebral spinal fluid (CSF),” details Dr. Belgrave. Once EPM has been confirmed, Dr. Waldridge’s next step is a frank conversation with the owner, as EPM treatment can certainly be more of a marathon than a sprint. “If we use ponazuril, we’re looking at a higher expense over a shorter 28-day timeframe versus sulfa pyrimethamine, which is more of an older school method that takes about three months,” says Dr. Waldridge of two common options. “I also will typically add a few days of a corticosteroid. We rarely have a treatment crisis as we’re killing those organisms; they’re more inflammatory once they’re dead. We’ll add natural vitamin E as well. There’s good evidence that vitamin E is beneficial to the nervous system as these horses are healing, and we’ll give it with a loading dose, then have the horse on a maintenance dose after that,” he adds. To add to the unexpected nature of EPM, each case’s outcome is unique. As in so many conditions, there’s simply no one-size-fits-all treatment plan or prognosis.

With so many horses being seropositive when tested for the offending parasites at hand, what’s the tipping point? Why do some become clinical and others never develop the signs of EPM? It comes down to the individual horse coupled with stress, the far-reaching super villain of the immune system. Veterinarians have witnessed previously asymptomatic horses experience stress from a number of situations — with travel being a primary offender — only to develop clinical signs of EPM. With stress as a contributor, maintaining the immune system becomes paramount in helping to support the overall health of the horse and its propensity for disease. Upwards of 75 percent or higher of the equine immune system resides in the gut. Providing horses with a diet based on high-quality forage and supplementing with omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, vitamins, trace minerals and gut-supporting ingredients like pre- and probiotics and L-glutamine is an important standard of care. The gut is often underappreciated, yet it plays a tremendously critical role in the overall health and function of the immune system.

EPM has most certainly been present throughout our past, but it was only in a span of time between the 1960s and the 1990s that the condition was identified, researched and understood as being caused by S. neurona or, less commonly, N. hughesi. Treatments have improved and cases with severe symptoms are simply fewer and further between than they once were. Where severely recumbent EPM cases were once a more regular occurrence, these days they’re thankfully more of a rarity. “I can’t remember the last time we had an EPM horse hospitalized in a sling, where 15 to 20 years ago, it wasn’t that uncommon,” remembers Dr. Belgrave. “With the emergence of the therapies that are available to us, and perhaps, maybe with more exposure to the organism, we just don’t see those really acute cases as much as we used to.” Dr. Waldridge agrees, “I think at least part of it is owner awareness. People are more cognizant and probably catch things quicker than they used to. The sooner you get these cases into treatment the better the chance that you’ll get your horse back.” With the opossum being the key offender in terms of spreading the parasites responsible for EPM, keeping feed and supplements in sealed containers is an important step, but Dr. Waldridge stops short of recommending opossum eradication on farms. “Some low-level exposure, in my opinion, isn’t the worst idea, especially on farms raising Thoroughbreds and sport horses that will experience a lot of stress in their lives. I’d rather they have some exposure and antibodies to that organism, instead of being raised in a pathogen-free environment, then having a sudden exposure and being under stress.” Dr. Belgrave is in the same camp. “From a preventive standpoint, epidemiologically, I do wonder whether prolonged exposure increases seropositivity to these organisms. We’ve seen a dampening of the severity of disease compared to 15 to 20 years ago, and that exposure has possibly played a role.”

While EPM in its clinical form remains a challenge with an uncertain outcome, the positives surrounding this condition are ever-present. Prognoses have improved and severely acute cases are more of a rarity than in the past partially because veterinarians have a solid and proven approach to both diagnosis and treatment. No rider wants to hear an EPM diagnosis, but hope, science and determined veterinarians are a powerful arsenal of players standing behind the horse and ready to fight.

Get to Know More in Our EPM Podcast

The evolution, clinical signs, preventive strategies and treatment protocols for more successful outcomes

Listen

by Jessie Bengoa, MS

Platinum Performance®

Contributing Veterinarian:

Rodney Belgrave, DVM, MS, DACVIM

Mid-Atlantic Equine Medical Center

Contributing Veterinarian:

Bryan Waldridge, DVM, MS, DABVP, DACVIM

Mississippi State University

A Closer Look

Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis

A Disease of the Central Nervous System and Brain, Often Presenting with Neurologic Symptoms

The condition is caused by the protozoa Sarcocystis neurona (S. neurona) and, in some cases, Neospora hughesi (N. hughesi)

“Some low-level exposure, in my opinion, isn't the worst idea, especially on farms raising Thoroughbreds and sport horses that will experience a lot of stress in their lives. I’d rather they have some exposure and antibodies to that organism, instead of being raised in a pathogen-free environment then having a sudden exposure and being under stress.”

— Bryan Waldridge, DVM, MS, DABVP, DACVIM,

Mississippi State University

Steps to Avoid Opossum Contamination

|

Keep feed and supplements in sealed containers |

|

Cover hay as much as possible |

|

Regularly clean your horse’s water trough |

|

Avoid feeding on the ground |

|

Manage the opossum population on your property |

Did You Know?

The opossum is a scavenger by nature (omnivorous). Several studies have demonstrated the presence of domestic cat, raccoon and striped skunk in the stomach contents. The opossum will scavenge carrion to survive if other more preferred types of food are not available.

Geographic Distribution of Horses with Antibodies Against EPM-Causing Parasites

Courtesy of the American Association of Equine Practitioners

The Three ‘A’s of Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis

1

Asymmetry

Describes a symptom that is worse on one side of the body than on the opposite side. In other words, with EPM, the signs are generally worse on the left side than on the right or vice versa.

2

Ataxia

Describes incoordination or the inability of the horse to know exactly where its legs are, resulting in inability to move its legs and trunk normally.

3

Atrophy

Describes a condition where the muscles shrink from their normal size. With EPM, this results from damage to the nerves that normally control or “innervate” these muscles. Muscle atrophy is not seen in all cases of EPM, so it is not as consistent a sign of disease as is the asymmetrical ataxia.

Signs of EPM

|

1 Stiff or stilted movements,abnormal gait |

|

2 Incoordination and weakness,which worsens when going up or down slopes or when the head is elevated |

|

3 Muscle atrophy,most noticeable along the topline or in the large muscles but can sometimes involve the muscles of the face or front limbs |

|

4 Paralysis of musclesof the eyes, face or mouth, evident by drooping eyes, ears or lips |

|

5 Difficulty swallowing |

|

6 Seizures or collapse |

|

7 Abnormal sweating |

|

8 Loss of sensationalong the face, neck or body |

|

9 Head tilt with poor balance;the horse may assume a splay-footed stance or lean against stall walls for support |