0 to 90

Major Milestones & Game-Changing Advancements in Colic Treatment

It’s difficult to imagine a time in modern veterinary medicine during which a horse undergoing colic surgery had a zero percent chance of surviving.

However hard to imagine, that was in fact the case. Prior to the late 1960s, very little was known about colic and its treatment. As a result, colic surgery was considered to be a near certain death sentence. It was at this time that veterinarians Nathaniel (Nat) White and Doug Herthel were interns at the University of California at Davis, under the mentorship of Dr. John Wheat. “When I started in veterinary medicine, colic surgery was a rarity. We didn’t expect survival,” remembers Dr. White. Dr. Herthel echoes the sentiment, “before 1968, colic surgery was not an option.”

“The year that 26 horses were operated on and one survived, Dr. Barry Grant was on the team, Dr. Richard Mansmann, Dr. John Terry and myself. It was such an exciting thing to have a horse survive that we took a 'win picture' with the veterinarians standing with the horse and the owner at UC Davis, holding the stone. It was a major event.”

— Dr. Doug Herthel

That all changed in the next decade when significant advancements were made in the diagnosis and treatment of colic. "It wasn’t until 1968 that we had our first success at UC Davis. Of 26 horses that were operated on, one horse with an intestinal stone survived," remembers Dr. Herthel. By today’s standards that survival rate is astoundingly dismal, but then each horse that survived was celebrated. “It was such an exciting thing to have a horse survive that we took a 'win' picture with the veterinarians standing with the horse and the owner at UC Davis, holding the stone. It was a major event,” says Dr. Herthel.

From the first survival at UC Davis nearly 50 years ago, diagnosis, medical treatment and the surgical approach to colic have evolved significantly, with several discoveries shaping the modern approach to such a ubiquitous and multi-faceted condition.

Unprecedented Breakthroughs

Starting with a zero percent chance at survival meant that the only way to move was upward. Veterinarians at UC Davis were eager to test new tools and techniques in the hopes of improving clinical outcomes for colic surgery patients. “If you had a surgical problem — a twist or a stone — it was a death watch of sorts because of the shortcomings of surgery. That was a big driving force to improve the surgical option when I was in school,” Dr. Herthel says.

The improvements made in general anesthesia, which changed outcomes tremendously, were a crucial leap forward. With the advent of anesthetics, such as halothane, that could be administered in oxygen, general anesthesia improved markedly, as it was much safer for the horses and provided veterinarians a way to deliver much-needed oxygen and intravenous fluids while the animals were undergoing surgery. However, progress didn’t stop there. “There was still plenty of room for improvement, and that included gas anesthesia combined with a ventilator, monitoring direct arterial blood pressure, oximetry and better fluid support,” says Dr. Herthel. “It made anesthesia extremely safe.”

These improvements helped allow survival rates to increase, slowly easing the fear surrounding colic surgery and giving horse owners hope for a positive outcome.

Trainer Justin Wright

with Dr. Joanie Palmero

The Race Against Time

Historically, the prognosis for colic surgery was so poor that veterinarians were hesitant to immediately refer a horse for surgery, even after the improvements in anesthesia and suturing had been made. “You had to get over the hump of horses being watched too long before they were referred. This made the prognosis even worse,” says Dr. Herthel. Dr. White agrees, “What helped improve survival rates was the realization that we were getting the horses too late. So, we worked on educating both veterinarians and clients, and referrals started happening more quickly. As a result, we went from a 25% survival rate to an 85% survival rate. A part of it was better understanding the physiology, but a huge component was getting the horses to us earlier.” Timing may seem simple, but it remains a problem even today as treatments and drugs become more effective at making horses comfortable in the midst of a colic episode.

The Threat of Diarrhea

With a better educational foundation in the study of colic combined with improved techniques, more horses were surviving colic surgery. Attention now turned to improving outcomes with better post-surgical care. It was a catch-up game of sorts. With over 10 years of attention focused on simply getting horses to survive surgery, the protocols for post-operative care were poised for significant breakthroughs.

One of the primary threats was diarrhea — caused by the use of both prophylactic and therapeutic antibiotics, the stress of not eating or by clostridial toxins. “The reason that there was only one survival out of 26 in the early days at UC Davis was that the other 25 horses succumbed to diarrhea,” says Dr. Herthel. “It was a major problem.” Progress was seen in practice as reliance on antibiotics eased, leaving healthier gut flora and a decreased occurrence of diarrhea post-operatively.

“Of course, there are instances in which horses need antibiotics, but there are ways of doing that where you can get a much lower occurrence of diarrhea,” says Dr. Herthel. “We were asking ourselves how we could doubly ensure that our patients didn’t break with diarrhea after surgery.” It was this question that led to one of the better tools in the fight against loose stool, the advent of Bio-Sponge®.

Bio-Sponge® began inside Alamo Pintado Equine Medical Center and was studied by prominent veterinarians in both clinical and university settings. “We started using therapeutic Bio-Sponge first, then went on to use it prophylactically,” explains Dr. Herthel. “Prophylactically, if you can prevent those toxins from being released you’re preventing a lot of serious complications for the horse and cost for the owner.”

The Influence of Diet on Colic Rates

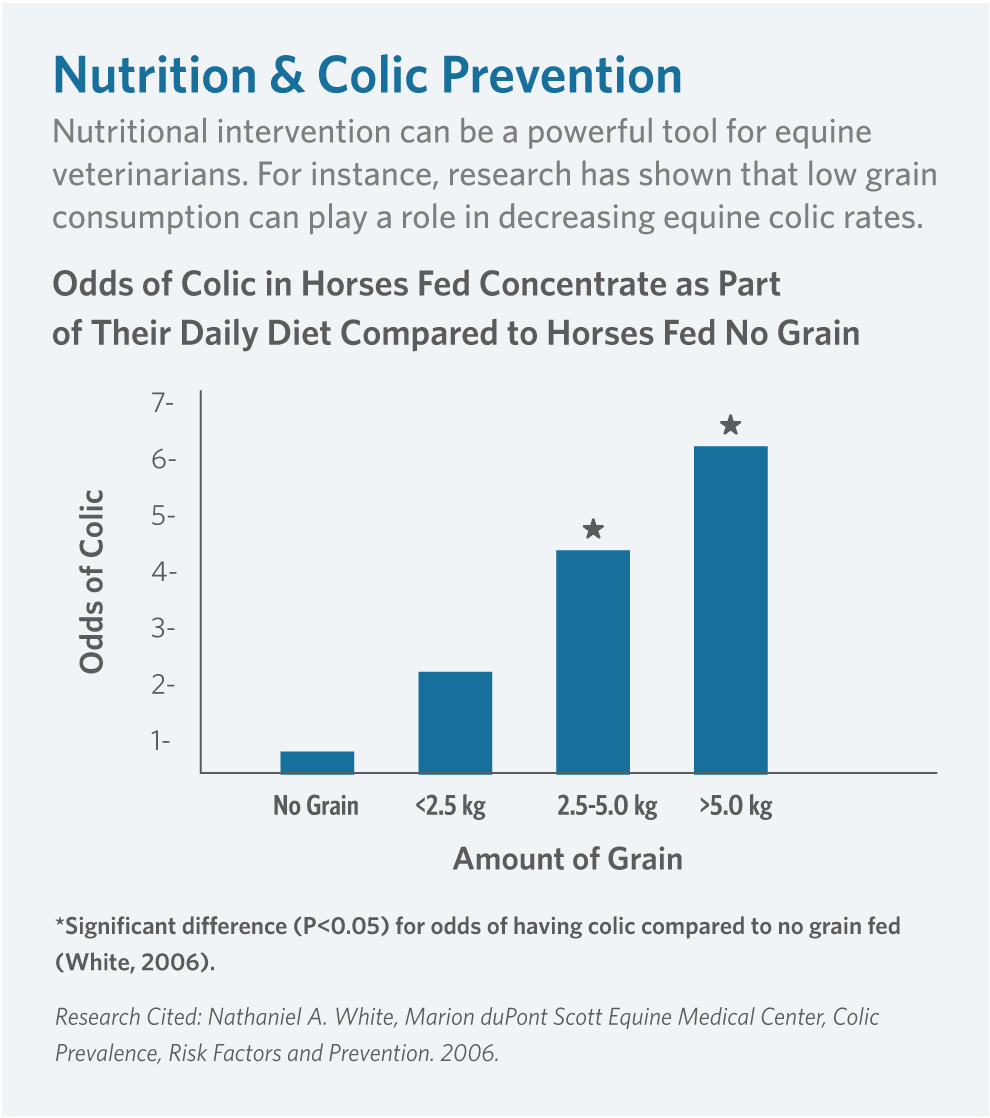

The idea of colic prevention has always fascinated Dr. White and became the topic of several important studies he has led. He was convinced, and remains so, that colic is a preventable disease that is influenced heavily by diet. “The research I’ve been involved with focuses on the epidemiology of colic — the problems and the risk factors that can be associated with colic,” says Dr. White. “Some of that has looked at colic on the farm,” he continues, “where we found that intake of high rates of grain are associated with a higher risk of colic. We suspect that even bran — regardless of its laxative properties — has such a high energy level that it is probably adding to the problem. We think that horses on pasture and turnout 24 hours a day are at less risk,” continues Dr. White. “And other studies have shown that’s true.” Indeed, a grazing diet of high quality forage is complementary to how the horse was designed to eat. As natural grazers, modern feeding practices of 2-3 meals per day with grains and concentrates easily shifts the types of intestinal microbes setting the stage for intestinal malfunction. For those horses where constant grazing is unrealistic, feeding only moderate amounts of grain with a high quality forage diet is the best way to decrease the risk of colic.

The Power of Nutrition in Prevention

"Colic surgery was great because you could save a horse that wouldn’t otherwise survive," says Dr. Herthel. "But still," he continues, "the best thing in the world is when you can prevent it in the first place." Dr. White agrees, "by all means, there are colic cases that I think we can prevent. Part of that is based on nutrition — limiting grain as much as possible, using healthy fats in the diet, practicing routine exercise and parasite control and turning a horse out as much as possible." Dr. Herthel concurs, "by mere husbandry we were able to decrease colon torsions dramatically by not feeding high concentrate diets and allowing a horse to graze off scabrous feed all day long."

Nutritional supplementation has proven to be a valuable source of beneficial fats in a horse’s diet, especially the omega-3 fatty acids that may be lacking without supplementation. Research has shown omega-3 fatty acids can support normal levels of inflammation. By adding an omega-3, antioxidant and micronutrient supplement to a high quality forage diet, a horse’s body is given what hay alone can’t provide. In addition, choosing a supplement produced without the heat or moisture required by the pelleting process allows for significantly lower rancidity to be introduced into the horse’s system. This can be a further benefit in preventing a range of digestive disorders and occurrences of colic. “If you have a horse in maximum work that needs a lot of energy, you can reduce the grain by adding healthy fats, potentially putting them at a lower risk for the shock that can be associated with colic,” says Dr. Herthel. “It comes down to the old adage, ‘you are what you eat,’ ” says Dr. White, “and horses are the same.”

“It’s a systemic disease. When the intestine gets injured, it affects the whole body. We’re now treating these horses for their entire system and seeing improved results.”

Name: Dr. Nathaniel (Nat) White

On the Horizon: The Future of Colic

With the progress that has been made in identifying the risk factors, prevention, treatment and surgical approach to colic over the last 50 years, it’s not hard to imagine that the future holds even greater promise. “One of the biggest things we know now is that colic is not just an intestinal disease,” says Dr. White. “It’s a systemic disease. When the intestine gets injured, it affects the whole body. We’re now treating these horses for their entire system and seeing improved results.”

Dr. White’s research has focused heavily on prevention, encouraging the use of diet to help avoid colic. His interest is also in the role intestinal inflammation plays in colic, which he expects to be an area of improved understanding and treatment in the near future. “Diet and inflammation play a role in the vast majority of equine diseases, and I expect our understanding of this to be increasingly significant in preventing colic,” says Dr. White. “The other research I’ve been associated with,” he continues, “is research into ischemia.” Ischemia is the shutting off of the blood flow that occurs when the intestine is distended or strangulated by twisting the vessels. “We’ve done some work to show what happens, and we know that even when we untwist the bowel, we still have a biochemical reaction that causes more damage. This is called reperfusion injury,” he says. “It’s the same thing that happens with humans when they experience a heart attack. You can remove the clot, but with new blood flow the body has a defense mechanism that goes overboard and causes more damage.”

Full Circle

The use of both prophylactic and therapeutic nutrition in colic prevention and post-operative care will continue to expand. “Our success rate will continue to increase as we better understand the role of nutrition in prevention but also as more horses are treated with it post-operatively,” says Dr. Herthel.

From their earliest days in veterinary school at UC Davis, Drs. Herthel and White, along with their colleagues, including Dr. Moore and Dr. Hassel among many veterinarians around the world in private practices and universities, have shared in the transformation of colic. Gone are the zero percent survival rates, replaced by 70-90% of horses returning home healthy after colic surgery. Thanks to innovations from anesthesia and suturing to Bio-Sponge®, post-operative tube feeding and nutrition, the stage has been set for further discoveries in regenerative medicine and ways to more effectively balance the microbiome.

“In the end, it all comes back to the horse,” says Dr. Herthel. “Colic is a prolific condition, and it doesn’t have to be.” He’s convinced that as science progresses the incidence of colic will decrease, starting with simple changes. “I hope there’s a time when colic surgery is a rarity because we’ve become so good at prevention,” he says. “A healthier horse is always the goal for every veterinarian, and I think we’re closer than ever to making a real impact on colic rates.”

by Jessie Bengoa,

Platinum Performance®

A special thank you to doctors Doug Herthel, Nathaniel White, Jim Moore and Diana Hassel for their contributions to this article and for sharing the story of equine colic treatment from its earliest successes to current research and hopes for the future.

Dr. Doug Herthel

Dr. Nathaniel White